Underneath the border of the United States and Mexico lie transboundary aquifers. Little is known about most of these aquifers or how the two countries can mutually manage these waters.

Within Texas Water Resources Institute’s (TWRI) Water Sustainability Program, research scientists with TWRI and Texas A&M AgriLife Research are studying these shared groundwater resources as part of a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) project to develop a comprehensive understanding of transboundary aquifers along the United States-Mexico border.

The USGS project, the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program (TAAP), was created by the U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Act of 2006 to conduct binational scientific research to systematically assess priority transboundary aquifers and to address water information needs of border communities. TAAP collaborators include the USGS water science centers and water resources research institutes of Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), stakeholders and Mexican counterparts.

The TWRI Transboundary Water Resources team includes project lead Dr. Rosario Sanchez, a TWRI senior research scientist; co-principal investigators Dr. John Tracy, TWRI director, and Dr. Zhuping Sheng, director of Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at El Paso. Laura Rodriguez Lozada, TWRI graduate research assistant, and Chunggil Jung, postdoctoral research associate at the El Paso Center, are also part of the project.

Collaborators include Gabriel Eckstein, professor at the Texas A&M University School of Law, and Dr. Kent Portney, director of the Institute for Science, Technology and Public Policy in Texas A&M University’s Bush School of Government and Public Service.

According to Sanchez, major challenges for the assessment and potential management of transboundary aquifers shared between Mexico and the United States include

- a lack of agreement on principles and criteria to define the transboundary nature and extension of an aquifer;

- a lack of data on hydrogeological conditions of aquifers located in the Mexico-U.S. border region;

- a lack of transboundary groundwater management assessments to identify stakeholder needs, concerns and priorities; and

- a lack of legal framework between the United States and Mexico to address the management of transboundary aquifers.

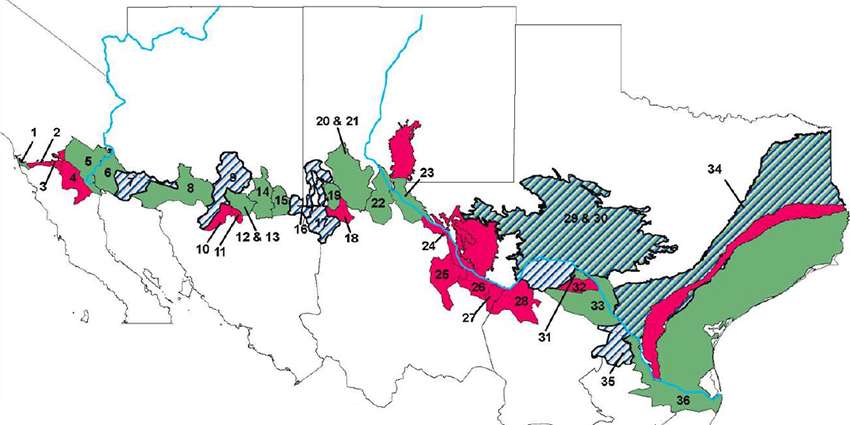

The Texas A&M team is focusing on enhancing the quantitative and qualitative understanding of the priority aquifers between Mexico and Texas (Hueco and Mesilla Bolsons), as well as creating a framework for identifying and assessing the condition of all transboundary aquifers on the Texas-Mexico border.

As of year two of the project, the team completed several of its objectives, including

- developing borehole data maps and cross-sections of aquifer formations, including physical boundaries, hydraulic connectivity and the first numerical model using MODFLOW for the Allende-Piedras Negras Aquifer to prove its connectivity across the border;

- completing an initial classification of all hydrogeological units located across the border between Mexico and Texas based on aquifer potential and water quality and publishing the results in the Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, Issue on International Shared Aquifer Resources Assessment and Management;

- updating the existing Hueco Bolson groundwater flow model, which will allow water managers to adequately predict how these changes will impact aquifer conditions and identify future actions that can sustain the long-term use of the aquifer;

- integrating a database of lithological and water quality data from all the available wells in the border region between Mexico and Texas to propose hotspots of pumping patterns to have an alternative aquifer area for transboundary aquifer management;

- accessing and analyzing perspectives from stakeholders along the Mexico and Texas border and developing new criteria and strategies for a transboundary groundwater cooperation model; and

- developing the transboundariness concept, which is an approach that evaluates and measures the strategic value of an aquifer that happens to be located at the border.

For the rest of the project, the team will:

- expand the geological correlation of hydrogeological units to the rest of the border between Mexico and the United States (Arizona, New Mexico and California) using the same methodology as with Texas and Mexico;

- exchange data between U.S. and Mexico partners through IBWC/ Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas (the Mexican section of IBWC);

- develop field work to assess surface water and groundwater interactions in the Allende-Piedras Negras Aquifer; and

- plan the Rio Grande Summit for the fall of 2020 where stakeholders from Mexico and Texas will meet and develop an action plan for groundwater to play a key role in determining the future of transboundary groundwater governance.

Sheng said groundwater flows across the border and doesn’t recognize the political boundaries and may change its flow direction when it is pumped heavily on one side.

“So understanding of the hydrological conditions and cooperation among water users on both sides of the border is critical for best management practices,” he said.

As part of its objective to develop protocols to identify transboundary aquifers, Sanchez said the team examined the concept of transboundariness to prioritize the aquifers.

Sanchez said transboundariness identifies and prioritizes transboundary aquifers using other variables in addition to their mere physical boundaries. It uses socio-economic and political criteria, such as the level of attention that an aquifer has received, population, groundwater level dependency and other factors to identify the vulnerability of transboundary groundwater resources.

“The transboundariness approach attempts to measure precisely those other variables,” she said. “This concept of transboundariness has the potential to offer an alternative approach for assessing aquifers where two or more international political jurisdictions meet and where the variable conditions of the overlying communities and its linkages with groundwater can actually be measured.”

“What evidence and information do we need to consider for an aquifer that underlies a border region to be defined as transboundary?” Sanchez asked. “Answers vary, and it is precisely that variation that transboundariness is able to identify and measure.”

Sanchez said the expansion of the methodology used to assess transboundary aquifers across Mexico and Texas to the rest of the border between Mexico and the United States will offer the only criteria ever developed between the two nations.

The TWRI project team has created a website, Transboundary Water Portal, to integrate and share data related to transboundary surface water and groundwater resources between Mexico and the United States.

The project team has also published several papers on this concept, including:

- Transboundariness or the end of aquifer boundaries as we know them.

- Transboundary aquifers between Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas, Mexico, and Texas, USA: Identification and categorization.

- The transboundariness approach and prioritization of transboundary aquifers between Mexico and Texas.

- Assessing aquifer storage and recovery feasibility in the Gulf Coastal Plains of Texas.

- Transboundary aquifers between Mexico and the US: Identification, classification and Priorization.

- Transboundary aquifers between Mexico and the US: Management perspectives and its transboundary nature.

- Aquifers Shared Between Mexico and the United States: Management Perspectives and Their Transboundary Nature.

- Identifying and characterizing transboundary aquifers along the Mexico-U.S. border: An initial assessment.

The team has also developed a Special Featured Collection on transboundary aquifers of the Journal of American Water Resources Association with an expected publication in the fall of 2019.

In addition, the team has participated in numerous conferences, including the TWRI-hosted American Water Resources Association Conference 2018 on Transboundary Groundwater Resources.

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Geological Survey under Grant/Cooperative Agreement No. G17AC00440.