Editor’s note: Hurricane Harvey and the resulting flooding brought national attention to the good, the bad and the ugly of what happens when hurricanes and extended rainfall hit the Texas coast. While many articles have highlighted the problems and the human-interest element, the next step is to look at what worked, what needs improving, and what research needs to be addressed to mitigate the effects of future extreme weather events in Texas.

We asked a group of Texas A&M University professors involved in different areas of water expertise and research — flood control and stormwater infrastructure, quality of drinking water, impacts to groundwater and impacts to bays and estuaries — to answer these three simple questions. Here are their answers.

FLOOD CONTROL AND STORMWATER INFRASTRUCTURE

Dr. Sam Brody, director, Center for Texas Beaches and Shores and professor, Department of Marine Sciences; and Dr. Wesley Highfield, associate director for research, Center for Texas Beaches and Shores and associate professor, Department of Marine Sciences, Texas A&M Galveston:

1. What worked during and after Harvey?

Time will tell and further investigations are needed to make firm conclusions about what mitigation strategies worked to reduce further impacts. That being said, preliminary analysis shows that subdivisions with better drainage infrastructure, elevated homes, newer structures built under more recent building codes, and homes far away from bayous or with barriers, such as roads, sound walls, etc. all faired significantly better during the storm.

2. What needs improving to address what didn’t work?

We need more regional, integrated and systems thinking when it comes to flood mitigation. This approach would involve collaboration across jurisdictional and organizational boundaries to consider regional watersheds and the cumulative impacts of development. We also need upgraded stormwater drainage infrastructure that includes regional detention facilities that operate on a watershed scale. Additionally, proactively identifying older, vulnerable structures for retrofit or removal-relocation would have reduced Harvey’s economic impact on the region. Finally, better messaging, education and outreach to homeowners about what to expect and what they can do in the face of repetitive flood events is critical in making the Houston region more flood resilient in the future.

3. What research needs to be addressed?

Several research topics have been identified by the Center for Texas Beaches and Shores on the Texas A&M Galveston campus:

- A proactive and systematic framework for land acquisition and buy-outs for flood protection.

- Understanding the relationships between hazardous facilities, water pollution and flooding events.

- Evaluating the performance of local and regional stormwater drainage infrastructure during storm events.

- Assessing the economic costs and benefits of specific mitigation strategies for flood loss avoidance.

- Developing and implementing web-based tools to communicate risk to homeowners across the Houston-Galveston Region.

- Identifying the impacts of regional development and land use change on flood loss.

- Predicting the impact of future development and land conversion on flood vulnerability and loss in the Houston-Galveston Region.

Dr. John Jacob, director, and Steven Mikulencak, Extension program specialist, Texas Coastal Watershed Program, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service and Texas Sea Grant

1. What worked during and after Harvey?

Neighborhoods that were carefully located on higher and well-drained ground performed spectacularly during Harvey. Houston has many such neighborhoods, for example the greater East End. Location is everything in a relatively flat place such as Houston. Within this flat coastal plain, there are extensive well-drained “ridges” (or watershed divides) that, while only 2-5 feet in total topographic relief over a couple of miles, drain stormwater very quickly. The worst flooding that most of the East End experienced during Harvey were streets flooded curb to curb or in some cases sidewalk to sidewalk. Much of the East End was urbanized between 1900 and 1950. The siting of neighborhoods was not dictated by land-use regulations, and yet they chose well.

2. What needs improving to address what didn’t work?

The continued siting of neighborhoods in floodplains needs better control through regulation or incentive. Harvey would have just been a nuisance (albeit a major one) had so many people not been living in floodplains, in many cases deep in the floodplains. Gulf Coast communities need stronger floodplain ordinances. (See The Bayou City can prepare for another Harvey–but only if we reclaim the floodplains and other Watershed Texas blog posts.)

3. What research needs to be addressed?

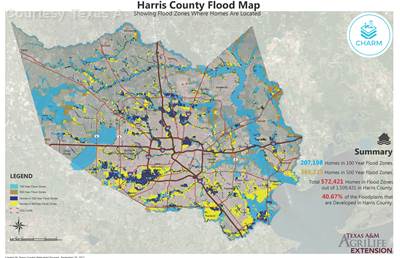

- The risk of flooding needs to be better delineated on maps and through communication. The 100-year, 1 percent chance flood zone may not be the safest benchmark for siting new development. (See the program’s planning websites: CHARMand Texas Citizen Planner.)

- Robust algorithms are needed to identify the lowest risk areas for new urban development. Floodplains, of course, are important, but things such as landscape shape (convex or concave) and slope may also be important.

- Research is needed to determine what is the cost of development in floodplains in the long run, and what costs are we counting or not counting.

QUALITY OF DRINKING WATER

Dr. Terry Gentry, professor, Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Texas A&M:

1. What worked during and after Harvey?

Governmental agencies did a good job of anticipating potential public health concerns and impacts on availability of water testing laboratories. My lab was contacted while the hurricane was still occurring to inquire about our operational status and availability to receive samples. (See this ABC News report.)

2. What needs improving to address what didn’t work?

We need to develop a strategic sampling plan for future events to better mobilize and coordinate sampling and testing resources available from surrounding areas. There are efforts underway to retroactively consolidate water quality data from samples collected after the hurricane. However, this data will likely be limited and geographically restricted since individual researchers and groups could only access and sample a limited number of locations immediately following the hurricane.

3. What research needs to be addressed?

Research is needed on the impact of the flooding on private water wells. Given the breadth of the flooding, many private wells may have been contaminated. In most cases, private water sources are not tested or disinfected prior to consumption, possibly causing lingering issues from any contamination event.

IMPACTS TO GROUNDWATER

Dr. Gretchen Miller, associate professor, Zachry Department of Civil Engineering, Texas A&M:

1. What worked during and after Harvey?

One of the biggest issues with flooding and groundwater is well-head protection. It is important that private well owners test and, if necessary, disinfect their wells after they have been submerged. Contaminated flood waters can leak into a submerged well, particularly if there are openings or cracks in its concrete well pad, cap or casing. I have seen the issue addressed in both the press and social media, and several efforts, like those by AgriLife, aimed at ensuring well owners can access free testing. This development is very positive and could prevent a good deal of suffering from water-borne illnesses.

2. What needs improving to address what didn’t work?

Unfortunately, flooding in the Houston area was almost certainly worsened by the over-extraction of groundwater. How? Since the early 1900s, high groundwater withdrawal rates have combined with the area’s underlying geology to cause sinking of the ground surface, a process known as subsidence. In some areas, the current elevation is as much as 10 feet below its original level. Lower elevations make flooding worse, as they create areas that are below sea level or are prone to ponding. Houston is just the latest casualty of this process; both Mexico City and New Orleans have suffered from similar effects. Unfortunately, subsidence is irreversible, so we need to address over-pumping in areas of Houston, which have not yet been impacted by subsidence but are potentially prone to it. This is particularly important in northern Harris County, which is growing rapidly and not yet under strict regulations.

3. What research needs to be addressed?

In my area, the biggest scientific question associated with the flooding relates to groundwater recharge. How does the prolonged saturation of the soil, along with high water availability, change the subsurface stores of water? Do large scale flooding events contribute significantly to aquifer storage, or are they over too quickly to make a lasting impact? While these questions center on natural processes, there has been tremendous interest in Harris County in using stormwater runoff, or even flood water, for artificial recharge of groundwater. This possibility is the subject of an ongoing project I have with the Harris County Flood Control District. (Listen to Houston Public Media’s interview with Harris County Precinct 4 Commissioner Jack Cagle and Russ Poppe, executive director of the Harris County Flood Control District: Harris County is Studying New Ways to Deal with Excess Rain Water.)

IMPACTS TO BAYS AND ESTUARIES

Dr. Rusty Feagin, professor, Coastal Ecology and Management Lab, Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Texas A&M:

1. What worked during and after Harvey?

The spirit of Texas citizens certainly worked during Harvey to help those in need, both in the areas affected by the wind and surge and the flooding rain. Our lab and department contributed to this effort with our skills in navigating shallow water with specialized boats and personnel, as called upon by the Governor. The clean-up has been difficult but surprisingly fast in some areas. The wetlands survived well as they usually do during hurricanes, and the erosion was generally not all that much along the beaches and dunes, with a few minor exceptions.

2. What needs improving to address what didn’t work?

There is not a lot that works or that can be done when it rains upwards of 50 inches in spots over a few days. We need better planning, engineering and natural ecosystem solutions for urban areas like Houston-Galveston, but we also need to think about land use and flooding in rural areas. The damage there has been overlooked, and it is generally worse on a per-capita basis.

3. What research needs to be addressed?

We all have our own research interests, but collaboratively we need to make sure that scientific data collection and research efforts crucial during and after the storm continue to be supported. Proposals by the current administration seek to severely reduce or eliminate support for the scientific missions of several of these critical agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tidal gauges, the National Weather Service predictions, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warnings, Federal Emergency Management Agency recovery efforts and social- and health-work agencies, but also agencies closer to home such as Texas Sea Grant or the Texas General Land Office were essential.