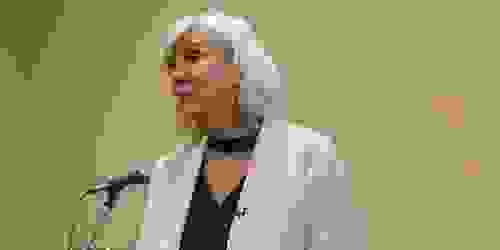

Dr. Joan B. Rose, an international expert in water microbiology, water quality and public health from Michigan State University, has spent her career trying to answer the question: How safe is the water?

“People want a simple answer: ‘Yes, it is safe; no, it is not safe. If it is not safe, then what do we do about it,’” Rose said, adding that there is no simple answer.

“We have all these water quality issues, and they are directly linked to public health,” she said, citing degradation of fresh water systems around the world, including ecosystems and recreational, drinking and agricultural water.

Well known for her work in water quality and public health, Rose spoke at at the Texas A&M University’s Water Daze lecture on April 3, presenting her research on water quality around the Great Lakes and what the findings mean to public health.

“The Great Lakes are an amazing place for science, aquatic science in particular,” Rose said. The lakes’ water quality has been studied since the 1900s and in 1913 was the focus of the largest ever bacteriological study with coliform.

One of her first studies in Michigan involved the 1993 cryptosporidium outbreak in the Milwaukee water system, the largest water-borne disease outbreak in the United States, Rose said. Fifty percent of the city’s population, or 400,000 people, became ill and 100 people died.

Rose said cattle were initially blamed, but research studies showed that human sewage was the cause.

“Even so, all the water tested met all the requirements of the Safe Drinking Water Act,” she said.

Before this outbreak, water officials thought that with the modern disinfection techniques, they didn’t have to worry about microbes anymore. “But then cryptosporidium changed that,” she said. “This one outbreak changed the nature of the re-authorization of the Safe Drinking Water Act.”

Rose said the question that has been asked for years since high levels of fecal indicators, such as E. coli, were found in water is “where in the heck is this (pollution) coming from?” The current indicator system for identifying pollution sources “only gives a hint of what is going on. We are just now getting to the point where we can answer that,” she said.

“If we are going to solve our water quality problems, we will not solve our problems with compliance monitoring using these techniques,” she said. “So we must go to water diagnostics to solve our big problems.”

In a large, watershed-scale study of fecal pollution sources across the lower peninsula of Michigan, Rose’s research group used several of these water diagnostic tools for microbial source tracking, including a new method that allows greater accuracy and precision. Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction, a type of DNA fingerprinting, is used to identify species-specific bacterial strains.

Rose said the study was undertaken because the ecosystems and water quality around that area are degrading, in part due to the transition of wetlands into agricultural lands.

The study included 64 river systems and 84 percent of the lower peninsula drainage area under three flow conditions.

Their results identified septic tanks and animal manure as nonpoint pollution sources and showed a relatively high number of those monitoring sites were contaminated with human and bovine markers. However, Rose said, high concentrations of E. coli did not equal high concentrations of the human marker.

From the results, they learned that the new microbial source-tracking tools are important and the pollution arising from septic systems are “likely more important than we had realized.”

She said they still need to know more about the markers. Some recent studies have shown better correlation between the concentration of markers and specific pathogens compared to using E. coli as the indicator. “If the marker is there in a certain concentration, then it is more likely and highly probable that the pathogen is there, so that goes back to health risk,” she said.

Rose said key watersheds were identified for further assessment and restoration and they are currently studying those watersheds.

Rose holds the Homer Nowlin Chair in Water Research at Michigan State in the Departments of Fisheries and Wildlife and Plant, Soil and Microbiological Science. She currently leads the Global Water Pathogens Project in partnership with United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Her work addresses the study of viruses, source tracking markers and protozoa in the water environment; use of new molecular tools for surveying and mapping water pollution for recreational and drinking water, irrigation water, and coastal and ballast waters; assessment of innovative water treatment technology for the developed and developing world; and use of quantitative microbial risk assessment.

Rose also spoke at the Texas A&M School of Law on “Water Quality and Health Challenges and Solutions."

The Water Daze event was sponsored by the Water Management and Hydrological Science program, the Texas Water Resources Institute, the Texas A&M University School of Law, and the Bush School of Government and Public Service.

Watch her College Station lecture and her Fort Worth lecture.