By Sara Carney

When visitors travel to Caddo Lake on the Texas-Louisiana border, they may see people canoeing on the blue-green water, navigating between the towering bald cypress trees and the Spanish moss that sweeps down from the branches. They may see fishers catching largemouth bass and families hiking nearby trails. But what visitors might not see is a creature beneath the lake’s surface that is older than the lake itself; in fact, it comes from the oldest animal lineage in North America.

Described by some as looking “bizarre” and “ancient,” the American paddlefish lacks scales and has a long, spatula-shaped snout equipped with electroreceptors that detect the fish’s next plankton feast. This fish can grow 5 feet long and live about 30 years, though some have reached 7 feet and lived 50 years.

After decades of absence, the paddlefish was returned to Caddo Lake in March 2014.

This return is not the first attempt to re-establish Caddo Lake’s paddlefish population. In 1994 and 1998 more than a thousand paddlefish were unsuccessfully stocked in the lake. But, there is one crucial difference between this reintroduction and others: environmental flows.

Flows matter

The term environmental flows refers to the amount of water that must move through a freshwater body, such as a river, and the timing of this movement to maintain native biodiversity and ecosystem processes. Environmental flows affect virtually every aspect of a river’s ecology, including water quality indicators, such as dissolved oxygen, pH, nutrients and temperature.

Historically, Caddo Lake had high flows into the lake in the late winter and early spring and low flows in the late summer and early fall. According to experts, these flows defined the lake’s ecosystem, including native fish species, such as the iconic paddlefish.

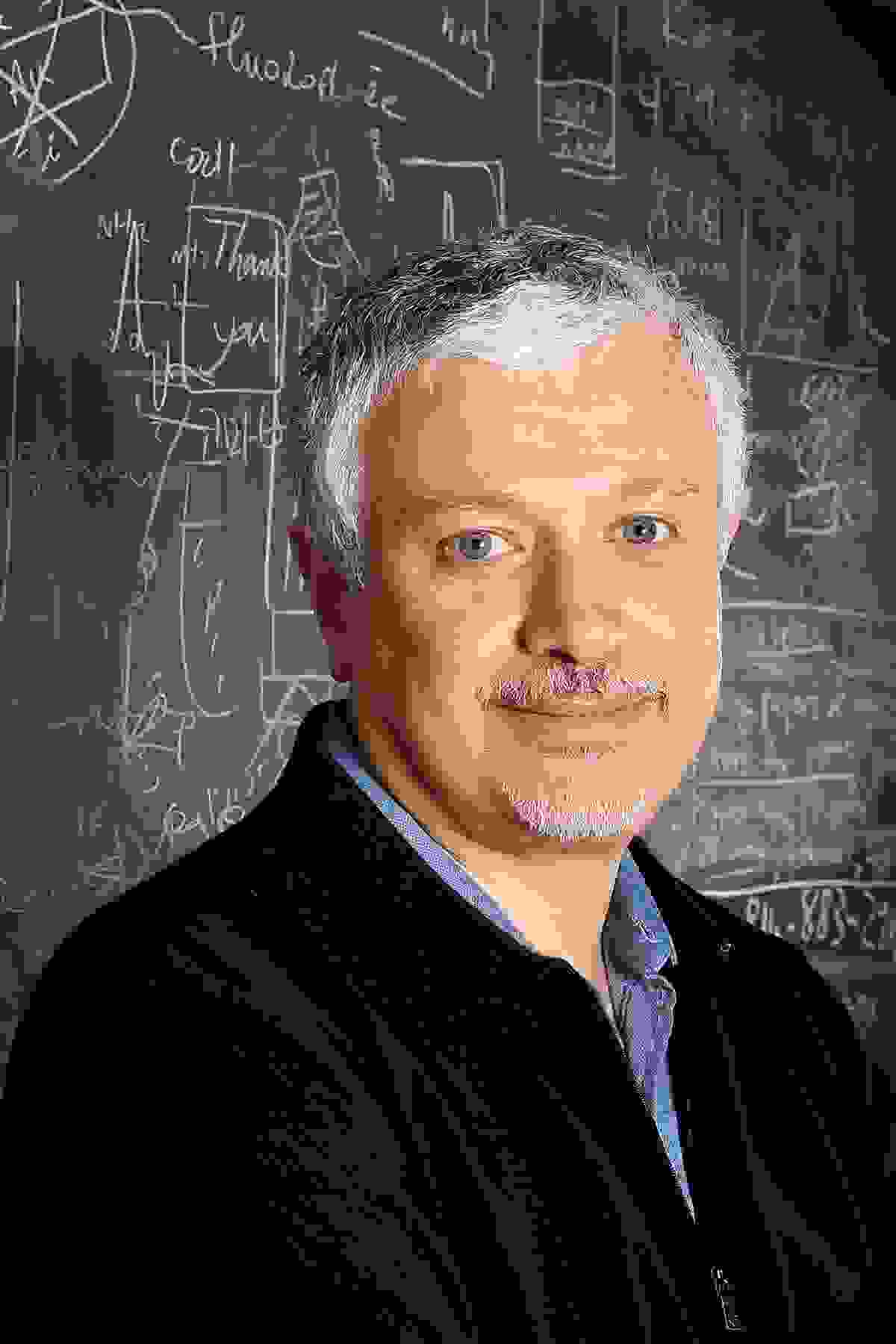

By synthesizing available data, Texas A&M University scientists developed a report in 2005, which revealed the importance of seasonally variable flows to Caddo Lake’s ecosystem. The report indicated that both plant and animal species are affected by flows, said Dr. Kirk Winemiller, an aquatic ecologist in Texas A&M’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences and an author of the report. For example, many fish species, such as the paddlefish, rely on high flow pulses as signals that trigger migration and spawning.

The dam that forever changed Caddo Lake

The majority of water flowing into Caddo Lake comes from the Big Cypress, Little Cypress and Black Cypress creeks. Along Big Cypress Creek, before reaching Caddo Lake, lies the Lake O’ the Pines Reservoir, which was created by building Ferrell’s Bridge Dam. This reservoir provides flood protection and water supply to Jefferson and surrounding cities.

Environmental flows affect virtually every aspect of a river’s ecology, including water quality indicators, such as dissolved oxygen, pH, nutrients and temperature.

The construction of Ferrell’s Bridge Dam in 1959 reduced winter and spring high flow pulses as well as base flows that naturally occurred throughout the year, according to the Texas A&M team’s report. This meant that some species within the lake no longer had the flows needed to maintain healthy populations, Winemiller said.

Experts believe it is possible to reduce flood damages and maintain water supplies while managing flows in a way that is beneficial to the environment, an issue frequently faced in managing dams. “That is the balance that people are trying to maintain across our state and throughout the world,” Winemiller said.

Through collaboration among a number of organizations, the Texas A&M team’s recommendations to replicate key components of natural flows are being translated into action.

Working with flows

This attempt to restore flows in Caddo Lake and its tributaries is relatively recent. In 2004, the Caddo Lake Institute (CLI) teamed up with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) Sustainable Rivers Project and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to start the Cypress Basin Flows Project.

The project began with data collection by scientists, such as the Texas A&M team, to ensure that this effort would be as well informed as possible, said Rick Lowerre, CLI president.

Once there was enough evidence that changing how water is released would benefit the ecosystem, the project began flow changes in 2011. In agreement with the Corps of Engineers and the Northeast Texas Municipal Water District, the flows project was set for a five-year period, during which the flows will be adjusted by the Corps of Engineers to mimic natural flows.

“The Corps and other partners have really been working to implement some of the scientists’ flow recommendations, those changes in operations of the dam, and to do so in coordination with the scientists, so they can monitor the responses downstream,” said Andy Warner, program coordinator for TNC’s Sustainable Rivers Project.

Sources agreed that the flows will likely never be fully restored to their original state, but they say there is no doubt that flows can be managed so both the needs of the environment and the people are met.

Caddo Lake’s whistle-blower

Scientists cannot feasibly study every species in an ecosystem, so they often pick one or more indicator species to monitor ecosystem health. These species act like a whistle-blower, alerting scientists to potential ecosystem threats. Indicator species’ population declines can be an early warning sign that factors such as pollution may be affecting the ecosystem. In Caddo Lake, a chosen indicator species is the paddlefish, due to its sensitivity to flows and threatened status, Winemiller said.

The flows will likely never be fully restored to their original state, but they say there is no doubt that flows can be managed so both the needs of the environment and the people are met.

Paddlefish were once abundant in Caddo Lake, and in the 1940s and 1950s there was a commercial fishery for paddlefish at the lake. It wasn’t until the Ferrell’s Bridge Dam was built that paddlefish began to decline.

“The paddlefish was extirpated after the dam was built; that tells us something has happened,” Winemiller said. The fact that previous reintroduction efforts that did not include flow changes were unsuccessful further indicates that the change in flows may be directly linked to the paddlefish’s survival in Caddo Lake, he said.

The paddlefish’s local extinction was merely a symptom of a changing ecosystem, he said.

“The whole project is really about more than just the paddlefish,” said Tim Bister, the local fisheries biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD). “The bigger picture is creating a more natural river flow throughout the year by having certain water releases from Lake O’ the Pines mimic that natural river flow.”

The paddlefish comes home

After the joint effort to restore natural flows based on scientists’ recommendations, conditions were ripe for the paddlefish’s return to Caddo Lake. “We’ve prepared the way this time,” Lowerre said. “I think before they were just reintroduced without anybody thinking about what changes might be needed to encourage them to stay.”

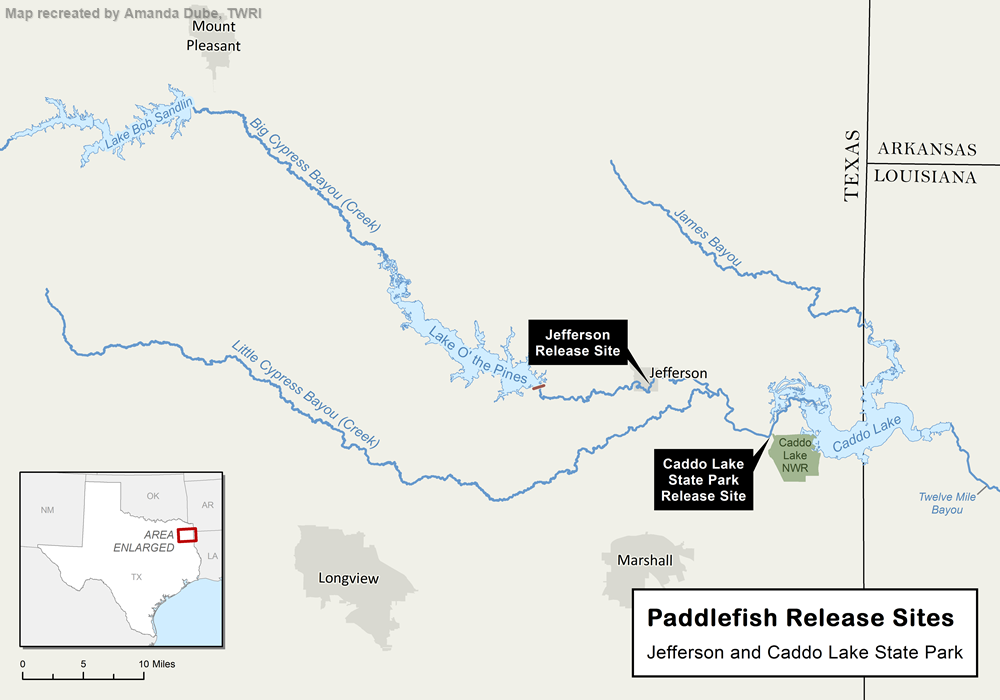

In March 2014, TPWD and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) released 47 young paddlefish from the Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery in Oklahoma into Big Cypress Creek. The fish were about 2 feet long and a year and a half old, Bister said.

Currently, these 47 paddlefish are being monitored via radio transmitters by USFWS and TPWD. Each time a paddlefish passes by one of the stationary towers near Caddo Lake, its location is recorded, Bister said. Tracking data is then uploaded to CLI’s website, so that anyone can view their movement.

The bigger picture is creating a more natural river flow throughout the year by having certain water releases from Lake O’ the Pines mimic that natural river flow.

A major concern was that the paddlefish were going to escape over the Caddo Lake spillway, where the dam would block them from swimming back upstream. But this does not appear to be happening. So, when the Tishomingo hatchery asked if TPWD wanted an additional 2,000 paddlefish for Caddo Lake, Bister said, “Sure, let’s get them in there!”

That September, those 2,000 paddlefish were brought from Oklahoma to Texas to join the first 47.

The paddlefish are expected to begin spawning at 7 to 8 years old. “I think having a healthy, naturally reproducing population of paddlefish will be a sign that the restoration work by all the partners is moving that system in the right direction,” Warner said.

Paddlefish educate local communities

One of the greatest benefits from the paddlefish release was the educational opportunities it brought, the experts said.

“The paddlefish is a way to help explain why we are doing these environmental flow studies and trying to change the system,” Lowerre said.

“Without the paddlefish, it’s hard for people to envision what it means.”

Several local schools have “adopted” and named paddlefish. Through CLI’s website, students or anyone interested can monitor the activity of “Don the Fish,” “Polly Sprinkles,” “Flat Billy” and other adopted paddlefish.

The potential for paddlefish to educate people about environmental flows extends beyond monitoring their movement. In May 2014 Collins Academy in Jefferson hosted the first Paddlefish Festival, an educational event for local schools to learn about Caddo Lake. The event included nature walks, mobile classrooms and student presentations.

Educational opportunities are not just for kids. TPWD holds workshops at Caddo Lake State Park to teach visitors about Caddo Lake’s history, the local plants and, of course, the paddlefish.

Efforts continue

The paddlefish restoration is simply the beginning, a way of reminding people of the value of the best course of action for the paddlefish and the ecosystem as a whole.

While the paddlefish is a small piece within the Caddo Lake ecosystem, the Caddo Lake ecosystem is a small piece within Texas’ ecosystems. “The Caddo Lake situation is a model for the rest of the state,” Winemiller said. “Hopefully, in the future, we will see more cooperative efforts like this in other parts of the state.”

Ultimately, both the paddlefish reintroduction and the flows projects are meant to preserve the ecosystem long term. Lowerre said, “We want this system healthy for not just this generation, but for generations to come.”