If you ran into Paul Montagna, Ph.D., on the Corpus Christi beach or one of his famous Friday night pizza parties, you probably wouldn’t realize that he is among the top 2% of researchers in the world for scientific impact or that he contributed to the largest environmental settlement in history.

When Montagna first started seriously considering the potential career he might have, he never imagined this is how it would turn out. He certainly didn’t expect he’d end up becoming the Chair for HydroEcology at the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, as he is now.

At the time, he wasn’t even sold on the idea of going to college. The only reason Montagna decided to enroll in college was to defer from the army.

“The Vietnam War was raging at the time and if you went to college, you didn’t have to join the army. I figured I’d give myself a few more years, then join,” he said.

However, a few years into Montagna’s undergraduate studies, there was a draft lottery, and his number was never picked. This left him at a crossroads. “I didn't even want to really go to college, now what am I going to do?” he remembers thinking to himself.

He experimented with teaching, but after a few stints working in schools, he realized that wasn’t the right career fit. So he decided to return to school to continue exploring different career options.

Although he was on track to obtain a master’s degree in biology, he felt that he lacked a sense of direction and purpose. “Graduate school felt like getting on an escalator at the mall,” he said. “You get on and you’re moving, but you have no idea what’s on the second floor.”

He will never forget his first graduate advising meeting. When Montagna’s advisor asked him what he would be interested in working on, Montagna vaguely responded that he might be interested in forestry.

“They didn’t have anyone working on forests at the time, but they said I could work on bays and estuaries,” Montagna said.

Montagna was pleasantly surprised and a bit puzzled by his advisor’s response.

“You mean I can work on something that I love and make a career out of it?” he said. “It's amazing how that never occurred to me before graduate school.”

Montagna’s love for water originated from fishing trips with his father on the Long Island coast when he was a child.

“My dad’s favorite hobby was fishing, and we would take out a little fishing boat just about every Sunday in the summers,” he said. “I actually didn't like fishing, per se, but I really loved being out on the water and being so close to nature like that.”

After finishing his master’s degree, Montagna took a job as a research assistant in the School of Oceanography at Oregon State University. After a few years, he decided to return to school to obtain a doctoral degree at the University of South Carolina.

Montagna landed in Texas when he accepted an assistant research professor position in the Marine Science Institute at the University of Texas at Austin in 1986. He recalls this being an especially exciting time to study freshwater inflow in Texas.

“It was the ‘80s when people in Texas really started to realize that the mixing of freshwater and saltwater that makes the Texas coast so productive,” Montagna said. He considered and still considers Texas a leader in freshwater inflow research.

“There has been a continuous commitment from the state to walk and chew gum at the same time,” he said. “They make sure to provide water for the health of people and the environment.”

During this time, Montagna was on a team commissioned by the Texas Water Development Board that was tasked with answering the question: “How much water does a bay need to stay healthy?”

Montagna thought the question was simple and could likely be answered with a few measurements. It turned out to be much more complicated.

The research team determined that the key to answering the question was to focus on how the flow from a river to a bay changes the biogeochemical condition of the environment.

“It turns out that simple question is really something that I’ve spent my entire career answering in many ways,” he said.

“Some of those reports eventually wound up influencing 2007’s Senate Bill 3, which forms the basis and framework for the way environmental flows are managed in Texas today,” he said.

Although Montagna’s primary research interest is still freshwater inflow, his water expertise spans many disciplines.

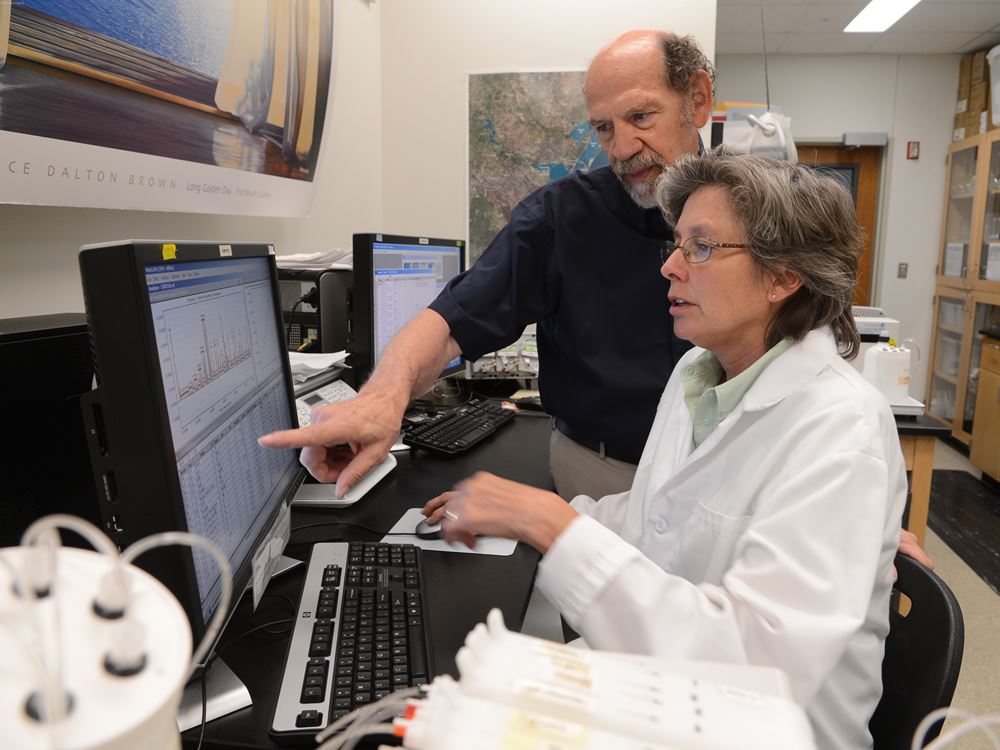

“When I was an assistant professor, I did a lot of work on offshore oil and gas, oil spills, and seeps. So, when Deepwater Horizon happened, I was asked to lead the deep sea assessment for the federal government.”

The British Petroleum (BP) Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 caused over four million barrels to flow directly into the Gulf of Mexico.

Montagna’s team found increased hydrocarbons, increased petroleum metals and reduced diversity in the area surrounding the blowout site. Their findings contributed to the $22 billion environmental settlement from BP.

“Knowing we played a small role in helping that all happen makes me really happy and really, really proud of all of the work that we did,” he said.

Projects like these, with relevant and large-scale impacts, motivate Montagna to keep doing the work that he does. Although he hardly considers his job work anymore.

“No one ever asks artists or writers why they keep doing what they do. I think it is because we all inherently understand that when you are in the creative business it’s not work, it is just doing what you love,” he said. “I’m at the point where this hasn't felt like work for a very really long time.”

However, he admits this has not always been the case. “Believe me, it was really, really hard for the first 20 years,” he said. Montagna advises early career researchers to be persistent and work hard.

“It’s going to take a while to be successful, but once you are, it's so worth it; you will have the ability to make a difference in the world and to really be able to help solve problems. To me, it’s worth everything in the world, but the key is to not give up.”

Working on new projects also keeps Montagna motivated. He is currently leading a “rather large” effort to try to synthesize the research efforts on freshwater inflow to bays and estuaries in Texas from the last 30 years.

“I'm really excited about that. Hopefully, we will make a nice big report,” he said. “I get so much satisfaction out of seeing a blank page filled with characters and letters at the end of the day.”

“Some people like to go fishing, I like to sit on a beach in front of my computer and compose a few paragraphs about the environment,” Montagna said.