The U.S. and Mexico share underground water basins that span more than 121,500 square miles of the Borderlands. But the two countries have no regulations for managing those common aquifers, in part, because historically very little was known about them.

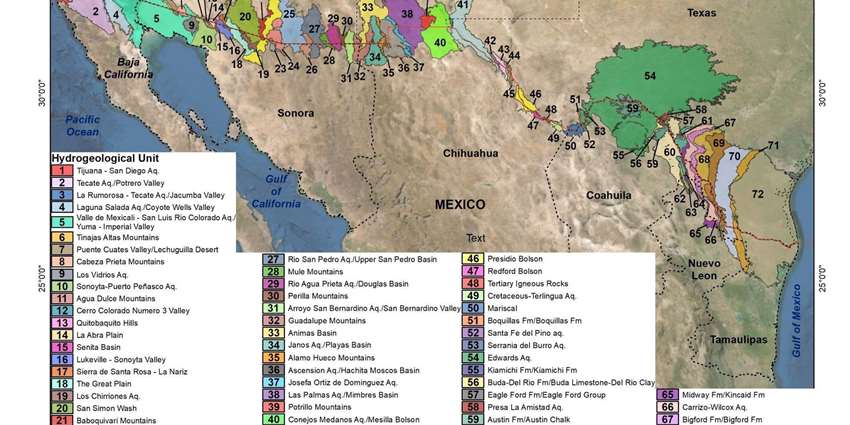

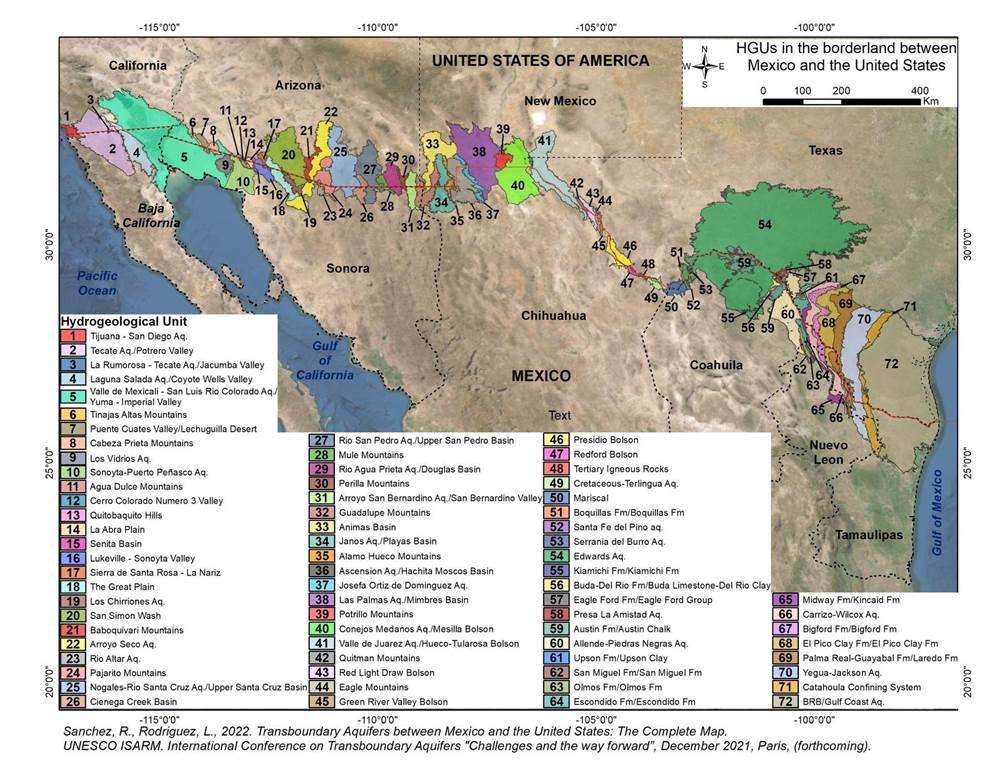

That’s changing. On Dec. 28, researchers released the first complete map of the groundwater basins that span the U.S.-Mexico boundary. It demarcates 72 shared aquifers — a striking contrast to the countries’ official count of 11. With water becoming an increasingly precious resource in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico, the researchers hope the new map will provide a basis for developing a binational legal framework to regulate the underground waters’ management.

“The lack of a legal framework that regulates the management of transboundary groundwater resources promotes the unsustainable use and exploitation of the resource,” wrote the authors, Rosario Sánchez, a scientist at the Texas Water Resources Institute, and Laura Rodríguez, a graduate student at Texas A&M University.

Their research, published in the book Transboundary Aquifers: Challenges and the Way Forward, builds on previous research that mapped segments of the Borderlands. It shows five shared aquifers between Baja California and California, 26 between Sonora and Arizona, and 33 between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas. Of these, 45% are considered to be in “good to moderate” condition.

One of the key contributions of the new research was to standardize the way that aquifers are delineated. While identifying aquifers might seem like a straightforward task, the two countries, and even individual states, have different criteria for where they draw the lines.

The researchers started by using those different definitions. “We put together what each state and country was doing, like a puzzle,” said Sánchez. But they realized that the data didn’t line up. “Texas uses geological boundaries, California uses a combination of watershed and geological boundaries, and Mexico uses administrative boundaries — a combination of geological and state boundaries. We realized that we couldn’t follow anyone.”

Instead, they put together their own methodology from scratch, drawing on geologic data from a wide variety of sources including 19th-century geological surveys. They determined the aquifer boundaries using geological formations and the type of rock present, as well as waterways, changes in elevation, and topography. “That’s why it took us 10 years,” said Sánchez. “It’s been hard.”

Alfonso Rivera and Randy Hanson, the authors of a 2015 report identifying 11 transboundary aquifers along the U.S.-Mexico border, wrote that the compilation of this geologic data is “an important stepping stone to reconcile how groundwater resources will be shared, governed and managed” as demand for groundwater increases.

Sánchez and Rodríguez hope that, at a minimum, the new research will prompt Mexico and the U.S. to update the official count of the number of aquifers shared between the countries. It also has the potential to prompt border states and the U.S. and Mexico governments to agree on a common methodology for identifying aquifers, and beyond that, a legal framework for managing them.

Felicia Marcus of the Water Policy Group added that maps like the one Sánchez and Rodríguez produced “are helpful for transparency and allow for more engagement of the affected communities,” particularly in resolution of disputes.

Conflicts over groundwater are already here, with widespread drought affecting both Mexico and the southwestern U.S. Meanwhile, New Mexico and Texas are fighting each other in the Supreme Court over groundwater pumping, California is implementing sustainable groundwater regulations, and Arizona is voting on citizen-initiated groundwater management areas — all of which could impact the cross-border aquifers. A legal framework for dealing with the international implications of those conflicts can’t come fast enough.

This article was originally published in High Country News.