Editor's Note: Carlos Rubinstein announced that he was stepping down as chairman of the Texas Water Development Board in June 2015 after the publication of the print article. This online version is updated to reflect the change.

To listen to Carlos Rubinstein is to understand his passion for water, particularly Texas water.

Whether he is speaking to a large crowd at a state water meeting or sitting around with friends on vacation, Texas water is almost always on Rubinstein’s mind and a topic of conversation.

Rubinstein is the former chairman of the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). He announced that he was stepping down as chairman in June 2015 and will continue to serve on the board until August 2015. Gov. Greg Abbott named Bech Bruun, a current board member, as chairman.

Rubinstein was appointed by former Gov. Rick Perry in 2013 after the Texas Legislature passed a bill changing the six-member, volunteer board to a three-member, full-time board. Involved in Texas water for more than 22 years, Rubinstein brought with him a wealth of experience and wisdom.

His office reflects both his years spent involved in water leadership and his personality. An old-fashioned, free-standing candy dispenser sits along a wall of windows overlooking the Texas Capitol. Plaques signed by officials recognizing his contributions to Texas water hang on the wall. He is especially proud of his Texas Water Commission- emblazoned leather chairs, reminders of Texas’ water past. The commission was the precursor to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

And over the years, Rubinstein has undertaken some of the biggest water problems the state has ever faced.

The charismatic, easy-going Rubinstein readily jumps from joking about his work habits to tackling seemingly overwhelming issues. And over the years, Rubinstein has undertaken some of the biggest water problems the state has ever faced.

Tackling Texas water planning

Arguably, the most pressing water issue facing Texas today is ensuring future water supplies amid its growing population, ongoing droughts and anticipated effects of climate change. The 2012 state water plan says that in 2060, the state will have 46 million people, double its 2010 population, and will be short 8.3 million acre-feet of water if the state does nothing in the meantime.

While some people approach this dreary outlook with skepticism or negativity, Rubinstein does not.

He attributes his optimistic perspective, in part, to the state’s forward-looking water planning process. Since 1997, state water planning has been conducted using a bottom-up approach. Every five years, each regional water planning group revises its region’s plan, charting water management strategies to meet the identified shortages for the next 50 years. These regional plans are then incorporated into the state water plan, which is designed to meet the state’s water needs during drought.

Rubinstein said other states compare themselves to Texas when it comes to water planning. “You would be hard pressed to find another state that plans for a 50-year horizon and revisits the plan every five years,” he said.

Because planning is locally driven, Rubinstein believes there is more ownership by those involved in the process.

You would be hard pressed to find another state that plans for a 50-year horizon and revisits the plan every five years.

“These regional entities understand what it means to them to not meet the goals and the needs we are going to have in the future,” he said. “The fact that we get to revisit the plan every five years is a great opportunity to shore up the plan and also to incorporate changed conditions. Some (of the projects) in the water plan may drop out of the plan, and that is OK. Because we revisit the plan every five years, we may have better options.”

Promoting new funds for water projects

In addition to the state’s progressive planning process, Rubinstein’s optimism has been reinforced by recent funding to move those water projects forward.

That funding is the $2 billion State Water Implementation Fund for Texas, or SWIFT, which the 83rd Texas Legislature passed and Texas voters approved in 2013. SWIFT, an affordable loan program, provides low-interest loans, extended repayment terms, deferral of loan repayments and incremental repurchase terms for projects in the state water plan.

From 1957, when TWDB was created, until now, the board has provided $15 billion in financial assistance, according to Rubinstein.

“In the next decade alone, with SWIFT, we are going to provide $8 billion worth of assistance,” he said, noting that the amount is a third of the $27 billion needed over the next 50 years to fund the 2012 plan’s water strategies.

In 2014, TWDB board members and staff traveled throughout the state, holding meetings about SWIFT and the rule for prioritizing projects to be funded. They held board meetings in Conroe, Lubbock, Harlingen, El Paso, San Antonio, San Angelo and Fort Worth and dozens of other meetings with communities statewide. The rule was finalized four months ahead of schedule, which Rubinstein called a “rewarding accomplishment.”

“Because we went out and talked to the public before we developed the rule, we incorporated a lot of comments into the rule,” he said. “When the rule came up for adoption, we didn’t have a single person sign up to comment on the rule, and that shows the value of having gone and met with Texans.”

Currently, the regional water planning groups and TWDB are working on the 2017 state water plan.

As part of Legislative changes made in 2013, regional groups have to prioritize their projects based on certain criteria.

Rubinstein expects sustainability, viability and feasibility to play the biggest role in determining which projects are in the 2017 plan and future water plans. Considering those three criteria will help groups determine if they are “really banking on the right project to meet their needs,” he said.

Rubinstein said the 2017 plan will have “better defined water conservation projects” that include associated capital costs. “The problem we have in the 2012 plan is several regions have conservation as a strategy, but there is no cost associated with it. And we can’t loan money where there isn’t a capital cost associated with it.”

Until the 2017 state water plan is adopted, Rubinstein said TWDB is addressing that issue by providing communities and regional water planning groups the flexibility to amend their current plans. They can add capital costs for conservation or add or revise other water management strategies.

TWDB’s staff is also making a concerted effort to push the water plan, its process and related data on TWDB’s website and through statewide talks. Having this information online helps the public understand the planning going on in their region. “Putting the data on the web, particularly for those small, rural communities, will provide them the opportunity to access data in real time and help alleviate some of the resources that they’re lacking,” he said.

Raising awareness of water conservation

Rubinstein believes that the state’s recurring droughts, including the most recent one, have brought greater awareness and ownership of water conservation to many cities and citizens.

Although a recent Texas Water Foundation survey found that only 28 percent of Texans know where their water comes from, the same percent found by a similar survey 10 years ago, he thinks the state has made progress in raising awareness of water and conservation needs.

“I know what the survey says, but there are parts of Texas that people clearly understand where their water comes from,” he said. “You can’t live in San Antonio and not know how reliant you are on the Edwards Aquifer; you can’t live along the border and not understand what the Rio Grande means to you; you can’t be from El Paso and not understand what the Hueco Bolson and the Rio Grande water coming from Colorado mean to you; and you can’t be in Wichita Falls and not understand exactly where your water comes from.”

This increased awareness, he said, has partly come from the media, but local media and communities need to play an even bigger role in getting people to understand the importance of water conservation. “It shouldn’t take a period of dryness for you to get it, but, regretfully, that is what has occurred.

“You can’t go into my neighborhood and not see signs flashing, reminding you every day that we are in Stage 2 water restrictions,” he said. His landscape irrigation timers are set for Stage 2, and he intends to leave them on those settings or lower indefinitely, drought or no drought.

It shouldn’t take a period of dryness for you to get it, but, regretfully, that is what has occurred.

Serving as TWDB chairman was not his first high profile water position. Rubinstein came to TWDB from TCEQ where he was one of three commissioners. He began at TCEQ in 1989 as a petroleum storage tank investigator, working his way up through the agency to deputy executive director, before becoming commissioner in 2009. From 1995 to 2000, Rubinstein worked for the city of Brownsville, which included serving as city manager, returning to TCEQ in 2000.

Championing U.S.-Mexico water treaty

It was at TCEQ that the Mexico City-born, Brownsville-raised Rubinstein became a champion for another significant Texas water issue: the United States-Mexico Water Treaty of 1944.

The two countries negotiated the treaty to outline allocation of the Colorado and Tijuana rivers and the Rio Grande from Fort Quitman, Texas to the Gulf of Mexico. The Amistad and Falcon reservoirs were built as a result of the treaty, and under the treaty, among other requirements, Mexico is obligated to deliver an average of 350,000 acre-feet of water annually from Rio Grande tributaries to the United States, and the United States is obligated to deliver 1.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River to Mexico.

The treaty worked well for more than 50 years, until the early 1990s, Rubinstein wrote in a recent Texas Water Journal commentary. “Since a drought in the early 1990s, however, Mexico has repeatedly—and what would appear to be also systematically—failed to meet its obligations in the 2 treaty cycles between 1992 and 2002, and is currently behind on its water deliveries in the current cycle that began October 25, 2010 and will end October 24, 2015,” he wrote.

It took candid discussions beginning in 2000 by both the Mexican and U.S. governments about Mexico’s incompliance during those treaty cycles, in which Mexico accumulated a 1.5 million acre-feet water debt, he said. In 2005 Rubinstein and others successfully managed to get Mexico to meet its water debt by what he called “creative management.” The group looked at how to better use the water in the entire Rio Grande Basin, not just the portions of the river in the treaty, he said.

The problem is not the treaty; it’s complying.

Now, Rubinstein, not one for backing away from a conflict, is seeking resolution to Mexico’s current 318,304 acre-feet deficit (as of March 14, 2015).

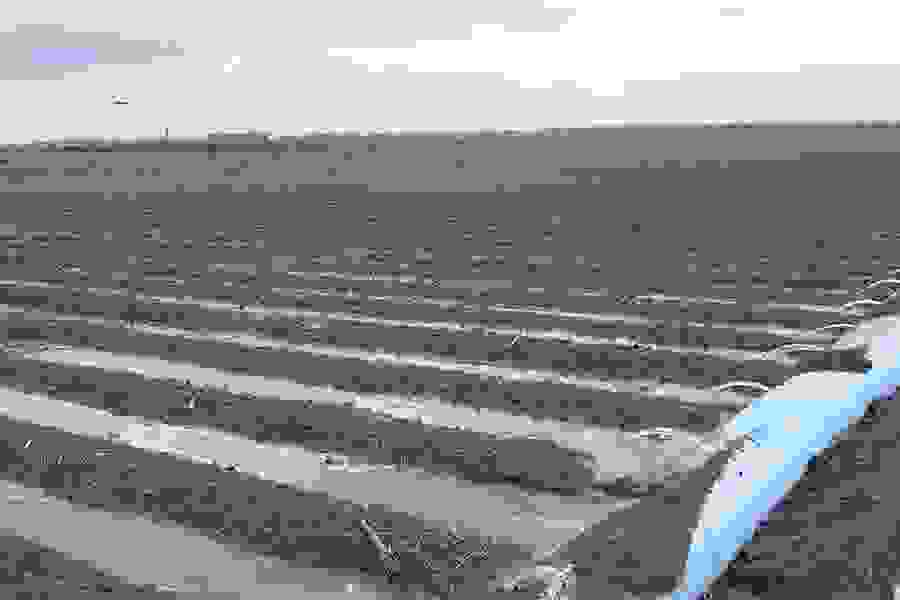

The impact of Mexico’s water debts, he said, has caused severe economic hardship for Rio Grande Valley farmers and cities. A 2013 Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service study identified that a loss of irrigation water in the Valley endangers about 4,800 jobs and reduces agricultural output by about $395 million annually.

“The problem is not the treaty; it’s complying,” he said. Mexico needs to recognize the United States as a water user under the treaty, to set aside water for compliance and to deliver that water, he said. “It’s that simple.”

With recent discussions, especially with the new Texas Secretary of State Carlos H. Cascos, for whom Rubinstein said the treaty was a “passion,” Rubinstein believes the two countries might be getting closer to resolving the issue.

“I do get a sense that we are getting closer and closer to that.”

Serving as a watermaster

While at TCEQ, Rubinstein also served as the Rio Grande watermaster for nine years. In that capacity, he oversaw the river’s water allocations below Amistad Reservoir. That job, in particular, put a face on the Valley’s water problems for him and made Rubinstein even more passionate about water issues.

“For those of us who have been watermasters, we will tell you that the only good time to be a watermaster is when your reservoirs are full or when your reservoirs are completely empty,” he said. “Everything in between is when you earn your paycheck. That is when you work with water users, and that is when you have to look a user in the face and say, ‘I am going to have to cut you back.’”

During the droughts of 2009 and 2011, while Rubinstein was serving as a TCEQ commissioner, the agency had to order water right curtailments. “We curtailed 1,200 water rights in response to senior calls,” he said. “When you understand what it is you are doing with that, yes, it makes you passionate about water.”

Rubinstein has many relationships with others in the Texas water world, and they understand each other. “People may agree or disagree with what I did as watermaster. People may agree or disagree with what I did as deputy executive director relative to water rights. People may agree or disagree with what I did with water as commissioner,” he said. “But that is good. It gives you a foundation of comfort that you know what you are talking about when it comes to water and that you have those relationships in the water world to be able to have those discussions.”

Dr. Ron Lacewell, assistant vice chancellor for federal relations for Texas A&M AgriLife, worked with Rubinstein during his time as Rio Grande watermaster. “People naturally gravitate to Carlos, for he never met a stranger and always shows more interest in your ideas and issues than his own,” Lacewell said. “He is a powerful, positive reflection on those he represents. Texas is lucky to have him helping plan for the future.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As the former communications manager for TWRI, Kathy Wythe provided leadership for the institute's communications, including a magazine, newsletters, brochures, social media, media relations and special projects.