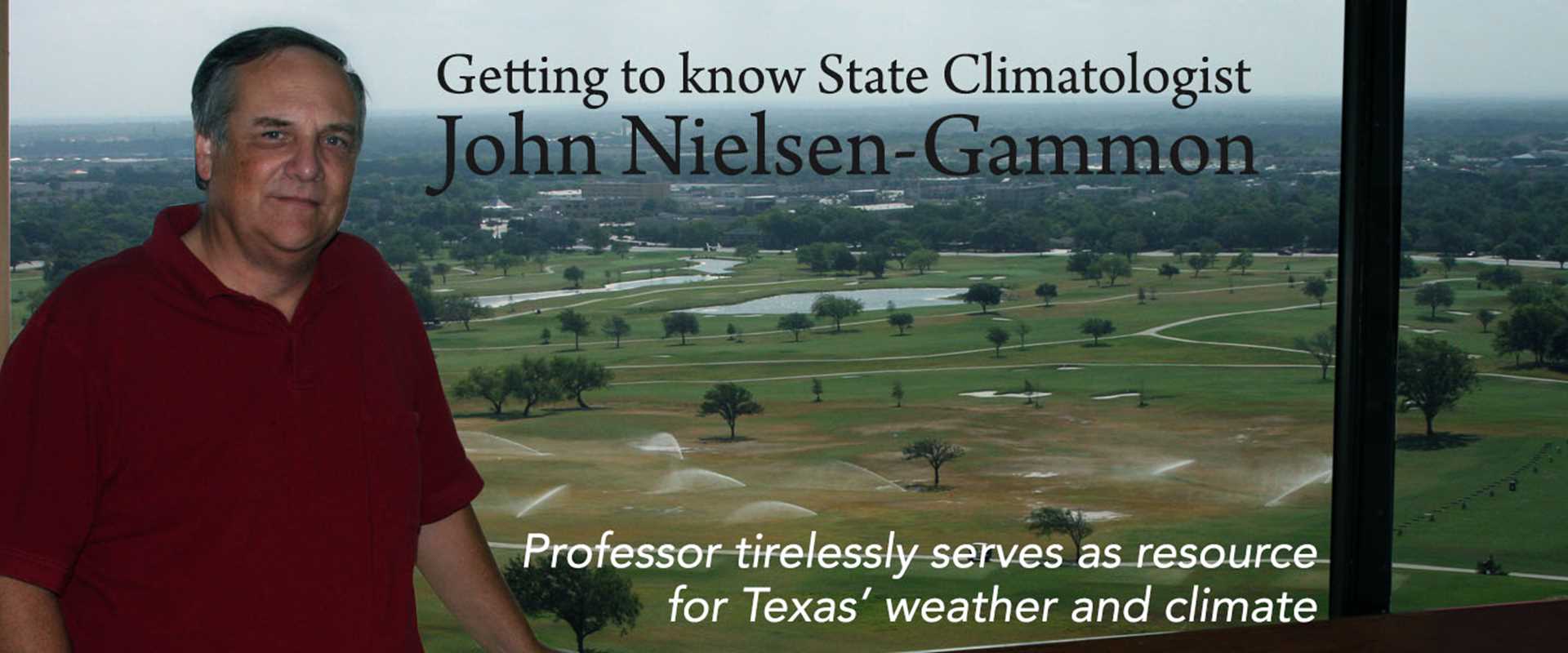

On the top floor of Texas A&M University’s Oceanography and Meteorology Building, overlooking the east entrance to campus, sits the Office of the Texas State Climatologist. Prior to the 2011 drought, its occupant, Dr. John Nielsen-Gammon, was a man very few people had heard of.

Since then, he has become a well-known resource for journalists, researchers, industry leaders and the public for information on the state’s weather and climatic conditions. Once people know they can rely on his office for a comprehensive perspective of what’s going on, they keep coming back.

About the Office

Nielsen-Gammon is one of 48 state climatologists in the United States, most of them located at land-grant universities. Appointed in 2000 by then Gov. George W. Bush, he is the second state-appointed Texas state climatologist at Texas A&M; Professor John Griffiths held the position for the 25 years prior.

The state climatologist’s job description is to help Texans make the best possible use of weather and climate information. Nielsen-Gammon monitors climate and weather, produces regular reports on the state of the climate in Texas, conducts research and serves as a liaison to federal government agencies for meteorological issues that affect Texas.

Base funding for the office is from the university, but Nielsen-Gammon also receives project-specific funding from state and federal agencies.

A lifetime of weather expertise

Nielsen-Gammon’s early expertise was in weather and air pollution. He received a bachelor’s in earth and planetary sciences and his master’s and doctorate in meteorology, all from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

He said his interest in meteorology dates back to long before college.

“It seemed like a fascinating topic, trying to understand things that happen,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “Weather is always happening to people, and it’s always changing, so there’s always something new to learn.

“Being the state climatologist allows me to directly apply my knowledge to help people, and I get the benefit of always having something different to do.”

A day in the life of the state climatologist

There’s no such thing as a typical day as state climatologist, Nielsen-Gammon said. Much of his work is outreach; he is invited to give about 40 talks a year throughout the state and is often interviewed by media personnel who contact him for climate and weather information.

Being the state climatologist allows me to directly apply my knowledge to help people, and I get the benefit of always having something different to do.

In May 2014 he started keeping track of his interviews, which totaled 184 by August 2015 with 56 interviews between May 12 and June 17 of 2015 alone.

Various professional groups also come to him for his expertise.

Nielsen-Gammon sometimes is asked his opinion on climate legislation proposed in the Texas Legislature. He also testifies two or three times per session in front of various committees on climate-related issues such as drought updates or climate change, he said.

He noted the most interesting group recently seeking his knowledge was professional engineers designing infrastructure that had to withstand the elements. They needed to know the expected frequency of floods, temperature ranges and other weather-related information to be sure their design could withstand the possible range of conditions, and they were interested in how to do that when the climate is undergoing long-term changes.

Participating in interviews and offering his expert advice account for only about half of his time.

As a regents professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences, the rest of his time is spent on typical university faculty duties — research, teaching, university service and other activities.

Overall, Nielsen-Gammon’s main research focus is Texas climate impacts. Because of his relatively broad background in atmospheric sciences, he believes he’s well positioned to understand different aspects of climate and climate change.

“I try to be sort of a generalist and talk about what we know about climate in general and what we don’t know and do general outreach through blogging.”

For several years Nielsen-Gammon maintained a Houston Chronicle blog titled the “Climate Abyss;” however, for the past couple of years, he has posted on the Climate Change National Forum.

The forum has 25 to 30 contributors who offer a “cross-section of perspectives from the scientific community both on science and possible policy options,” he said. “We can be a resource to people who want to hear what’s going on from different perspectives and not just have a single point of view put forward. We do require whatever people put forward be legitimate and founded on science.”

Figuring out the guessing game

From droughts to floods, hot to cold and all in between, Texas weather is constantly changing. Texas experienced the worst one-year drought in 2011. As of July 16, 2015, Texas was officially 100-percent drought free after record rainfall during May 2015. The state remained drought-free for two weeks, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Throughout the summer, drought popped back up and spread rapidly throughout the state.

A lot of his work as a state climatologist involves putting data into a historical context.

For example, in May he set out to estimate the statistical likelihood of the record May rainfall, which is probably much greater than one in 1,000 year likelihood, Nielsen-Gammon said. To do this, he took data from May, June, September and October of previous years, which are the climatologically wettest months in Texas, and plotted the number of months with particular amounts of statewide average rainfall in inches through 2014. He then added May 2015 onto the plot, and, in comparison, it topped the chart for record rainfall.

As the state resource for this type of information, he was contacted during the record May rainfall event and asked for more specific rainfall information.

“Halfway through the (May rainfall) event, I got a request from state officials to give them daily precipitation totals for a statewide average, and those numbers didn’t exist, so I had to figure out a way to calculate them.”

To determine this information, he put the state inside a grid with 100 squares and picked a weather station within or close to each square to make sure he had a representative average. There are several hundred weather stations that report regularly in Texas.

He said he waited until the end of the month to see if his predicted averaged numbers agreed with what the official averages were, and they came out pretty close.

The previous record for the highest amount of monthly rainfall events was in 1957, the year that ended the state’s worst drought of record.

“The next thing that happened in 1957 is we had a dry summer, then a wet fall, so history seems to be repeating itself,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “It takes more than two events to actually have a pattern, but so far it’s happening.”

These wet and dry events impact the historical frequency of dry spells in various cities in Texas. With this type of information, he can look at a city and see how often the city has gone at least 50 days in the summer without a half-inch of total rainfall.

Nielsen-Gammon is also responsible for determining the appropriate level of drought in Texas to submit to the U.S. Drought Monitor, a weekly map of drought conditions produced jointly by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Every week that passes with a particular area in the same dry conditions bumps that area into a more severe drought category.

Looking toward this winter, most climate forecasts are predicting a strong and strengthening El Niño, which favors a wet winter in many parts of the country because of the way the weather interacts with the jet stream, Nielsen-Gammon said. Using his historical rainfall data for November through March, he can choose a particular El Niño strength and see how much rain has fallen historically under similar conditions.

“With this event, we’re talking about something that will be out near the extremes of historical El Niños, so the chances of it being dry… Well, it’s never happened. It’s been above normal and close to normal, but it’s never been dry since 1950, which is as far back as we have good El Niño condition data,” he said. “It’s not a guarantee that we’ll have adequate rain, but it’s about as sure of a bet that you’ll get six months in advance.”

On the other hand, Texas only received near-normal precipitation during the two strongest El Niño events in recent history, 1982–1983 and 1997–1998. “While this winter should be wet, it may not be all that wet,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

While a lot of his work is focused on statewide average precipitation, most people are more interested in their local precipitation. Nielsen-Gammon maintains data to show folks in specific cities how the odds of rainfall change when narrowed down from a statewide average to a specific location.

“There’s a lot more variability in smaller areas, so some places will be unlucky even if the state gets above average rainfall.”

Conducting research and other activities

When Nielsen-Gammon is not looking at the climate and weather patterns, he is researching it. His main funded research is focused on drought, the state’s biggest climate issue.

Through work formerly supported by USDA and currently supported by NOAA, he estimates drought severity at a fine-scale resolution, which serves as input to the U.S. Drought Monitor. This county-level data is especially important because USDA has certain drought relief funding available depending on the Drought Monitor’s record of drought length and severity in the county, he said.

There’s a lot more variability in smaller areas, so some places will be unlucky even if the state gets above average rainfall.

“We need to make sure (the U.S. Drought Monitor is) getting every county right,” Nielsen-Gammon said. “We are taking recent data analysis from the National Weather Service and putting it into a historical context using long-term climate observations and converting that into different indices that measure drought severity at different time scales.”

He also works on many other research projects. Changes in runoff into Texas reservoirs, impacts of weather station location and land use changes on temperature records, and the roles of natural variability versus climate in changes in extreme weather events are just a few of the other issues he researches.

Aside from traveling around the state, researching and running the latest computer models, when Nielsen-Gammon is not at work, he likes being outdoors. Golfing and hiking are among his favorites. While there’s not that much opportunity for hiking in College Station, he manages to get out occasionally, he said. He also enjoys both listening to and playing music. “I like to go to Houston occasionally for the symphony or opera. I also play the piano for a folk group at weekly mass in Bryan,” he said. “I’m interested in everything.”

Looking ahead

Nielsen-Gammon said he’d like to eventually get back to full-time teaching and research; however, for now he plans to stay in the state climatologist role.

“Right now with everything going on, I find there’s a lot I need to do, and I think I’m a good person to do it,” he said.

“I’m working mainly at the local level. The things you can do to change the climate require global-scale action, but everyone has to adapt to whatever happens to the climate. Whatever I can tell people about what’s going to happen a year from now or 10 years from now is useful information.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

Danielle Kalisek is the Assistant Director for Institute Operations for the Texas Water Resources Institute. In this role, she manages institute business, particularly the pre-award through account setup processes and state and designated accounts, she also coordinates communications and websites services and needs for the institute.