Resiliency is defined as the ability to recover quickly from setbacks and a group of university researchers are examining just how resilient Texas may be to future changes in its population, climate and land use in the 21st century.

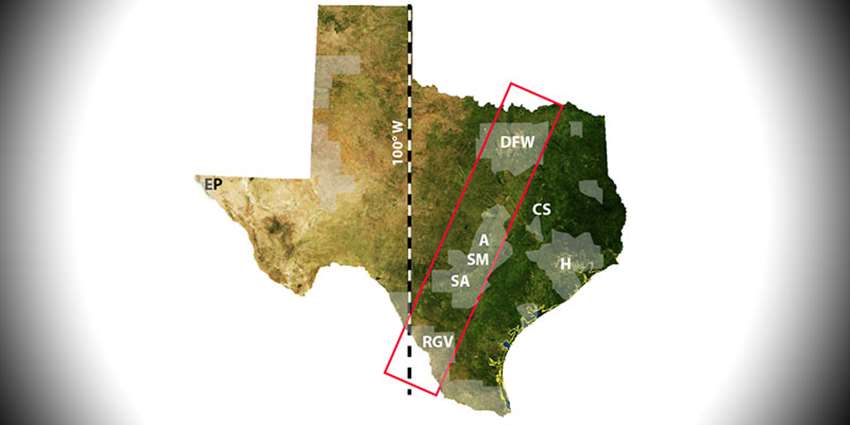

Just east of the 100th meridian lies a line of Texas’ largest and most rapidly growing urban areas, stretching from the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex to the Rio Grande Valley. It is along this corridor where the biggest changes in population, climate and land use are expected.

How will these changes impact the state’s already stressed water supplies? Can new policy, new technology, infrastructure investment, and an evolving human relationship with water reduce the risk and increase that area’s resiliency? Those are the questions the scientists are working to answer through a five-year, $500,000 National Science Foundation-funded grant.

The New 100th Meridian: Urban Water Resiliency in a Climatic and Demographic Hot Spot project includes 41 faculty from 15 universities in Texas and other states, along with stakeholders from diverse backgrounds and interests.

Principal investigators are Drs. Jay Banner and Suzanne Pierce of the University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin), Dr. Kevin Wagner from the Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI), Dr. Venkatesh Uddameri of Texas Tech University and Dr. Lloyd Potter of the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Banner, director of UT Austin’s Environmental Research Institute (ESI), said the project is named “the New 100th Meridian” because historically the 100th meridian, which runs through San Angelo in West Texas, delineated the arid western part of the United States from the humid eastern part. With the projected changes in climate, including the possible return of megadroughts, Banner said, that dry line is predicted to shift to the east. It would encompass a stretch from the Rio Grande Valley to San Antonio to San Marcos — the fastest growing city in the country — to Austin, up to Dallas and Fort Worth.

“We’re not actually saying the line of longitude is going to move; we’re saying that (climatic) boundary that is presently at the 100th meridian will move to the east,” he said. “And if it does extend so that the major municipalities are encompassed in it, then we face a very significant change in water availability in the region with longer droughts, less rainfall, warmer temperatures and generally more evaporation.”

Banner said “water resiliency” refers to whether or not the state, with its increased population and climatic condition changes, will be resilient enough to bounce back and still have enough water for all Texans and all uses.

The research group is focusing on the resiliency of the state’s urban water, Banner said, “because that’s where most of the population growth will occur, that’s where increased infrastructure will impact water quality, that’s where the increased number of people in the urban areas will increase water demand.”

The populations of the cities along the corridor are projected to grow significantly, with the state’s population projected to double by 2065.

“If there are twice as many people, then we have to think about very limited water availability compared to what we enjoyed in the 20th century,” he said.

The project’s overarching goal is to build knowledge regarding the factors that will impact future water resiliency in the rapidly changing human and natural systems of Texas.

The scientists will work in four research areas:

- identifying the “Grand Challenges” for understanding water resiliency in Texas;

- comparing downscaled 21st century climate model projections at high spatial resolution and improving understanding of the mechanisms that drive drought in Texas;

- developing 21st century scenarios of demography and regional development in Texas; and

- integrating the other three activities into a regional evaluation of future water resiliency for the state.

Banner said the project includes researchers from different disciplines because many environmental challenges are inherently interdisciplinary.

“You absolutely need hydrologists to understand water systems, water flow, groundwater, surface water, etc. but just hydrologists will not get you far enough,” he said. “We need demographic experts, social scientists and regional and community planning experts and climate scientists… that we have to bring to the table to address complex issues such as the future of Texas’ water.”

Taken together, research from the project should generate a better understanding of the human system of the urban centers, the natural system of the climate hydrological system and how those interact with each other, Banner said.

“We would have a better picture of how these systems work,” he said, “which may ultimately provide us with better predictive capabilities of what the future may hold.”

In conjunction with the project, Wagner said a research network was established to coordinate efforts to address these rapidly changing human and natural systems. The network’s activities focus on four research nodes:

- climate projections

- water science

- water and population scenarios

- resiliency and stakeholders

Wagner co-leads the stakeholders and resiliency research node with Dr. Suzanne Pierce of UT Austin-ESI. Researchers in that node are working to assess decisions and actions that might be taken by municipal, regional and state government and by area stakeholders to ensure future water resiliency.

“Our first step is to compile information from existing reports published by various groups around the state and use that to better assess and understand the challenges already being faced around Texas, the research needs, and the policy evaluation needs, and then work to better integrate our research with the identified needs,” Wagner said.

Banner sees the research network as a resource for researchers, policy makers and the public.

Banner said the team hopes their research and the network will be used practically and help guide changes in water policy, support greater adoption of water conservation and assist in developing new sources of water.

To read more information about the project and network, visit the ESI website.