Marshes, swamps, lagoons and bogs; there are many different types of wetlands, but did you know that they are capable of filtering wastewater?

Two innovative, constructed wetlands in the Dallas-Fort Worth area have the ability to divert over 180 million gallons of treated wastewater per day from the Trinity River and naturally filter it for reuse.

Tarrant Regional Water District (TRWD) and North Texas Municipal Water District (NTMWD) use constructed wetlands to help maintain a sustainable water supply. The current population predictions in the North Texas region are expected to double by 2060, increasing the need for a reliable, clean water supply.

Both water districts’ constructed wetlands were selected as 2018 Conservation Wrangler projects by Texan by Nature (TxN). The Conservation Wrangler program highlights the very best Texan-led conservation projects occurring in the state supporting them with tailored aid, resources and visibility, according to TxN program manager Taylor Keys.

Keys said constructed wetlands work like natural systems improving water quality through natural treatment mechanisms powered by sunlight, wind, plants and microbes.

“Water flows into the wetland slowly, and any solid matter in the water settles out in sedimentation basins,” she said. “The wetland vegetation then removes nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, improving the water quality.”

According to the TxN website, constructed wetlands remove on average 95 percent of sediment and 50 percent to 80 percent of nitrogen and phosphorus. This process improves the overall quality of water leaving the wetlands.

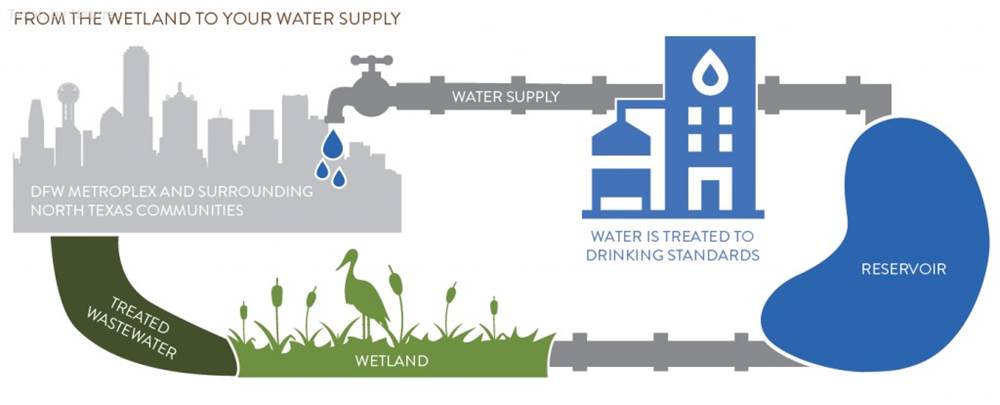

After the treated wastewater is diverted and filtered via the wetlands, Keys said it is returned to blend with other water supplies in reservoirs and treated to drinking water standards to be delivered to consumers for use.

“If location and planning for a project like this permits, a constructed wetland is a cost-effective alternative to building a new reservoir or extending the life of current reservoirs,” she said. “Wetlands delay the need to construct additional water supply projects, have a smaller footprint than reservoirs and can be implemented in a fraction of the time. These projects are critical for maintaining a sustainable water supply for the growing population of North Texas.”

TRWD’s George W. Shannon Wetland Water Reuse Project, in partnership with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Richland Creek Wildlife Management Area (WMA), was constructed in four phases over 22 years, starting in the early 1990s.

Keys said TRWD initially implemented a pilot-scale constructed wetland for proof of concept. The 250-acre first phase eventually expanded into 20 vegetated wetland cells that cover over 2,000 wetted acres located in the WMA.

NTMWD learned from TRWD’s 22-year project, Keys said, allowing it to complete the East Fork Water Reuse Project in three phases over five years, beginning in 2004.

The reuse project diverts up to around 95 million gallons per day from the East Fork of the Trinity River into a 24-cell constructed wetland that is over 1,800 acres.

Partners of the NTMWD water reuse project include the Rosewood Corporation and John Bunker Sands Wetland Center, which is situated on the constructed wetland and provides education and research opportunities.

Both districts worked together with Alan Plummer Associates, Inc., a consulting firm that provides engineering services related to water and wastewater infrastructure.

“TxN has worked with both water districts and their partners to increase educational awareness of the benefits of constructed wetlands in regard to water supply and to promote using the wetlands as educational and recreational opportunities while also providing habitats for wildlife,” she said.

Keys said that TxN would like to see other municipalities replicate what TRWD and NTMWD have done to positively impact the communities, economies and natural resources of their cities.

“We would like to see stewardship efforts for existing wetlands to maintain their healthy ecosystems in order to sustain their environmental and economic benefits for generations to come.”