Last year, amid widespread drought, a violent protest over water erupted in Chihuahua, Mexico, a state in the northwestern part of the country. Local farmers armed themselves with sticks, rocks and Molotov cocktails and took over the Boquilla Dam, which was holding the water they desperately needed to irrigate their crops. Two people died in confrontations with Mexican soldiers.

The water in question was supposed to be sent to farmers in Texas, part of a water payment under a 1944 treaty between the United States and Mexico that allocates water from the Rio Grande.

The dam standoff in Mexico hints at the conflicts that could arise as climate change and growing water scarcity strain this shared resource. But little is known about the state of the water that lies below the surface — the region’s shared aquifers.

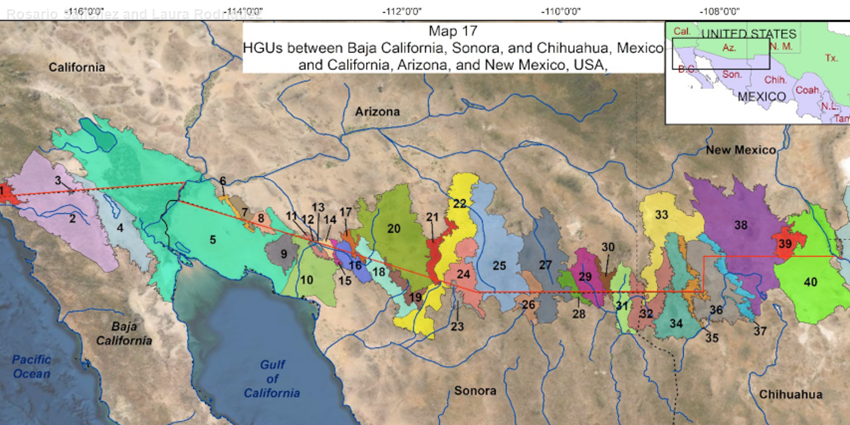

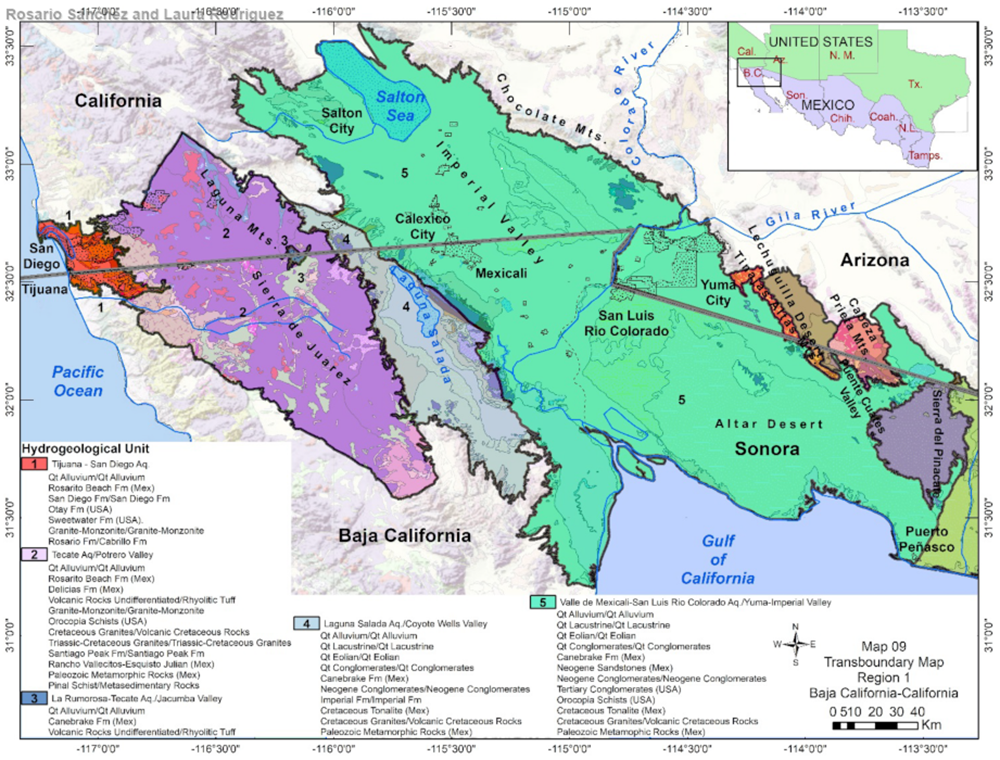

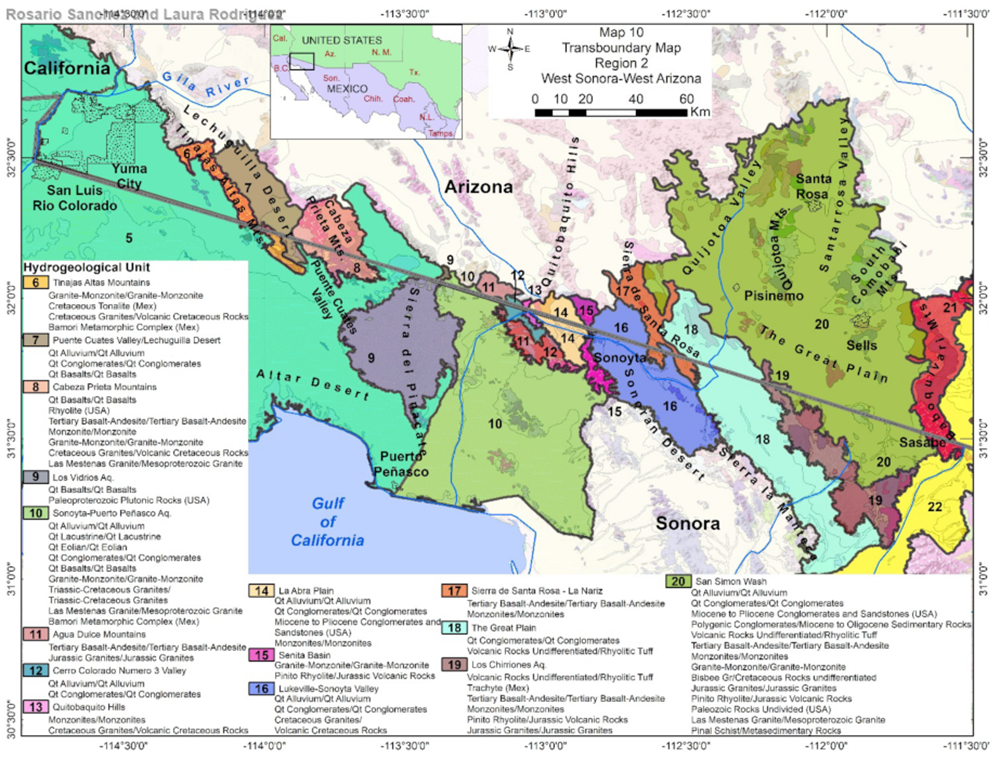

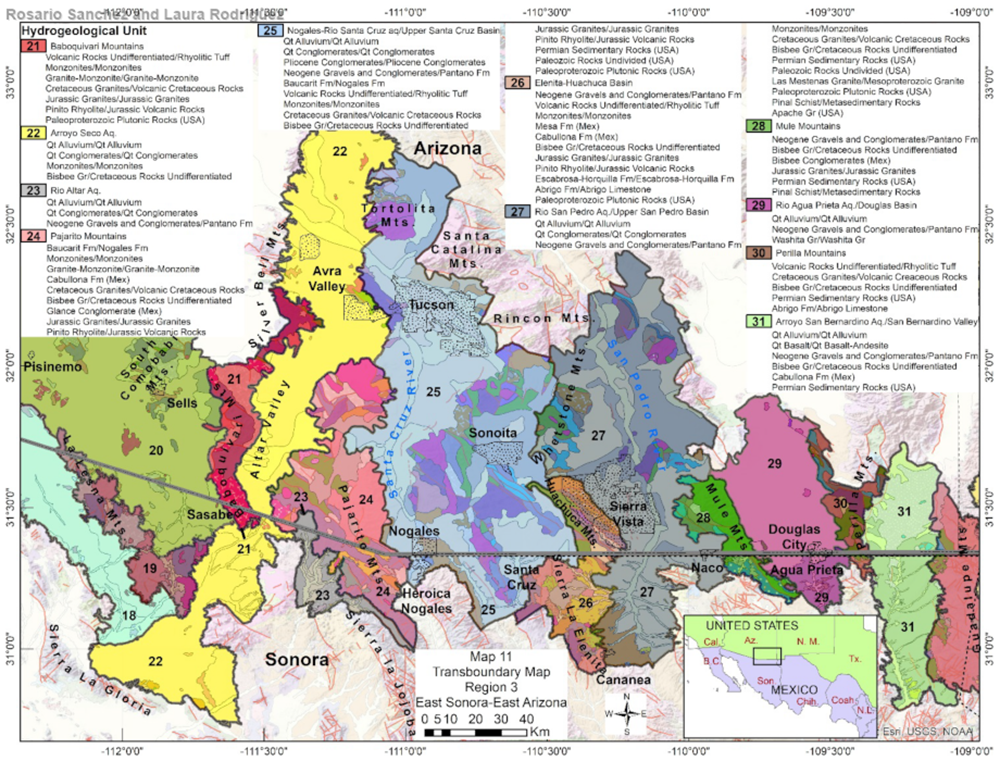

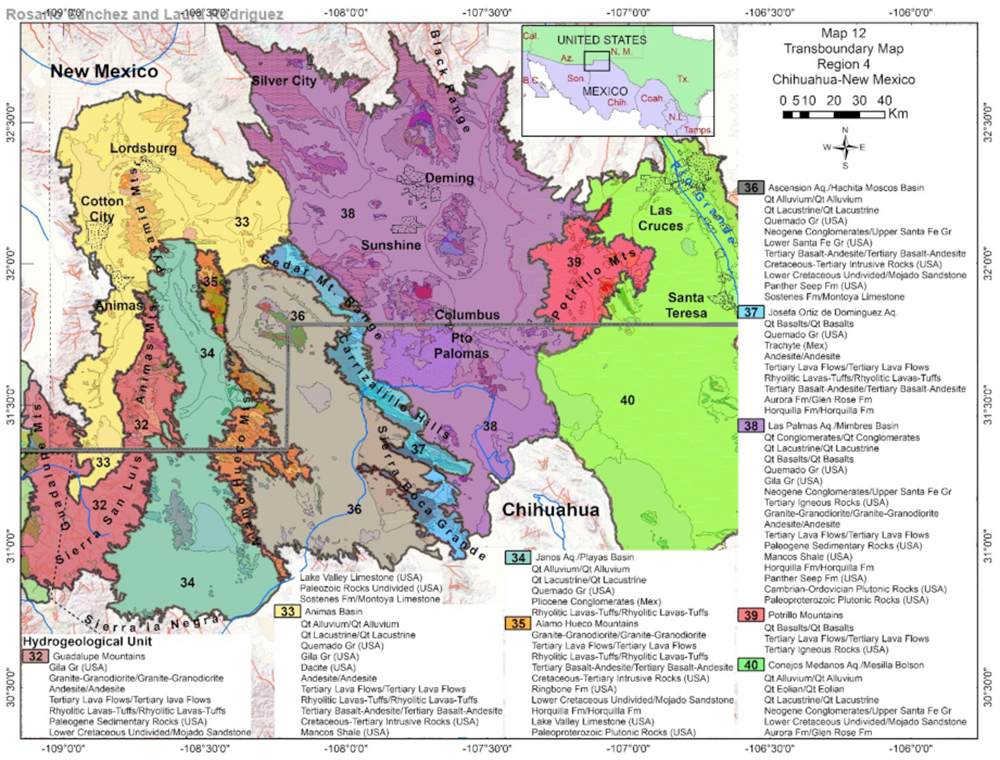

A recent study on binational groundwater could help change that. Published in October, a series of maps from two Texas researchers shows where underground water flows, and gives policymakers a standard tool for studying transboundary aquifers. Rosario Sánchez, a senior research scientist at the Texas Water Resources Institute at Texas A&M, and Laura Rodriguez, a geologist and graduate research assistant at Texas A&M, mapped 39 of these formations, which straddle the Borderlands in the Southwestern states of Arizona, New Mexico and California. Unlike the Colorado River, groundwater is not regulated binationally: The United States and Mexico have yet to sign any treaties to jointly manage them. In fact, both countries are still just beginning to understand the aquifers’ significance.

Researchers started by analyzing the available historical research, scientific literature and data from both sides of the border. They focused on geologic characteristics to determine their potential for storing water. If the rock is porous, for example, that could indicate that it can hold more water. According to their paper, around 40% show “good-to-moderate” aquifer potential, meaning that a significant amount of water could be extracted.

“This paper delves deeper than most in the critical role that the geology (bedrock, hard rock, crystalline rock) plays in the formation and understanding of southwest’s semi-arid aquifer systems,” Floyd Gray, a geologist with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), told High Country News in an email.

Prior to the October research, details about these transboundary aquifer systems were scarce. “The big problem is that all the boundaries that the countries used to delineate (the aquifers) they all stopped at the border,” said Sánchez.

The findings will inform a growing effort to understand what water lies underground. “Maps like these are very important to developing a common understanding of what these aquifer systems look like and their characteristics so that we can then get to some discussion,” said Sharon Megdal, director of the University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center, who was not involved in the research. For example: “What do we do about aquifers that appear to be overexploited?”

Still, many questions remain as scientists work to get a clearer picture of the transboundary aquifers. “This is a very good physical geological characterization, but it is not a model of groundwater use,” said Megdal. “You need to combine this sort of information with other information to get a more complete picture of what the groundwater situation is. ... What are the vulnerabilities?”

Megdal, who has participated in binational assessments of the Santa Cruz and San Pedro aquifers, which cross Arizona’s border into Sonora, said changing precipitation patterns and overuse are already impacting groundwater recharge. The Santa Cruz aquifer, for example, the main water source for Ambos Nogales, two border towns separated by the wall, already has a water deficit. “It is not going in a positive direction,” she said.

Groundwater management has taken on greater urgency around the world. In December, both Megdal and Sánchez will present their work at a UNESCO conference on transboundary aquifers that will tackle the question of governance. Sánchez hopes the United States and Mexico will collaborate on a solution.

“The reliance on surface water from both the Rio Grande or the Rio Colorado is really not an option for the future,” said Sánchez. “The water will be coming from groundwater.”

This article was originally published in High Country News.