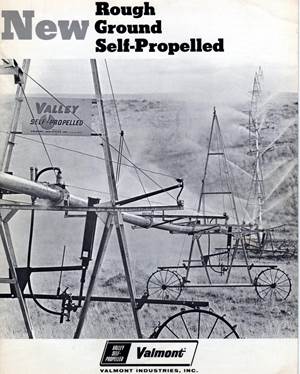

Center pivot irrigation system. (Thomas Marek, Texas A&M AgriLife Research)

Spanning from South Dakota to Texas, the Ogallala Aquifer is the largest freshwater aquifer in North America. But despite its size, the Ogallala is drying up. Scientists have reported for years that, if recharge and use continue at current rates, research shows that much of the Ogallala in Texas could be depleted as soon as 2100.

However, there are strategies to help slow the depletion, and one key could be rangeland management, according to new research published in Rangeland Ecology & Management and co-authored by Ed Rhodes, Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI) research specialist and Ph.D. student at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University at Kingsville.

“We posit that the art and science of rangeland management stands uniquely poised to tackle this challenge directly through creative integration, where appropriate, of native rangeland restoration, improved pasture management, integrated crop-livestock systems, and regenerative agricultural practices aimed at preserving soil and rangeland health,” Rhodes said. “Rangeland management can provide continuity in the ability of the Ogallala region to continue to provide food, fiber, and other ecosystem services both locally and globally.”

The article is co-authored by Humberto Perotto-Baldivieso, Ph.D., and Evan Tanner, Ph.D., of the Kleberg Institute; Jay Angerer, Ph.D., U.S. Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS); and William Fox, Ph.D., Texas A&M University Department of Rangeland, Wildlife, and Fisheries Management. Looking ahead to the eventual reality of the Ogallala no longer being able to sustain high farmland outputs in Texas, the researchers recommend transforming those lands to healthy rangelands that protect soils and wildlife and provide beneficial ecosystem services.

“People are used to the good soil areas being farmland and not a wild ecosystem anymore,” Rhodes said. “We’re saying that this area can be good rangeland again when it ends up becoming unsuitable farmland.”

The history of High Plains irrigation

Because the Ogallala supports one of the most agriculturally productive regions in the world, the High Plains, it is a vital resource and federally funded programs are working to help sustain the region. The Ogallala Aquifer Program, funded by USDA-ARS, has been working in the region since 2003. A few years ago, former TWRI Director John Tracy, Ph.D., was discussing ideas for the program with Rhodes, who suggested obtaining historical imagery for the area and analyzing land use changes.

Rhodes began working on that historical analysis and then began his doctoral studies at Texas A&M Kingsville, also studying the High Plains.

"Maps in the 1800s actually listed that area as the Great American Desert,” Rhodes said. “It’s a relatively dry area that was dominated by short and mid-grass prairie.”

The Homestead Act of 1862 was a major factor in the area becoming farmland, he said, with people enticed by the promise of free land, and while parts of the region had good to marginal soils, it was a tough settle. Periods of drought created a cycle of good years with profit, followed by years of failed crops and bankruptcy. Continued droughts and plowing led to disasters such as the 1930s Dust Bowl.

“The aquifer was known about, but at that time, the technology wasn’t really there to extract it,” Rhodes said. “After World War II, a lot of drilling and pumping technology started to take off, and then in the 1950s, the center-pivot was invented.”

Center-pivot irrigation, also sometimes called circle irrigation, uses sprinklers atop wheels to irrigate crops, and the wheels rotate around a center pivot in a circular motion. Now the most widely used irrigation method in the country, nearly 28 million acres were irrigated using the technology by 2013.

A new challenge to face

Access to the aquifer has helped the region overcome its reliance on uncertain rainfall and prevent more dustbowl disasters. Now the issue facing the region is, when will the water run out?

“There are a lot of different models and theories, but in the next 100 years, a lot of that area in Texas, Oklahoma, southern Kansas — those areas are going to go dry,” Rhodes said. Nebraska is estimated to have 200 years’ worth of water left, due to the aquifer being generally more thick up north, tapering down as it heads south, he said.

Depletion is a real possibility because of the aquifer’s low recharge rate, coupled with high rates of withdrawals from agricultural producers. In Texas, the aquifer recharges around 0.25 inches per year, while in Kansas it recharges up to 6 inches per year.

Center pivot irrigation system. (Kansas Research and Extension)

“For all intents and purposes, it’s not a renewable resource,” Rhodes said. “We’ve stretched it out a long time, and they might stretch it to 120 or 130 years with the next improvements in technology, but it’s still going to run out, because we’re not putting anything back into it.”

“With the amount of food and fiber being generated from this area, as far as the United States’ agricultural output, people need to start thinking about what is going to happen in this region when you have to go back to relying on just rainfall,” he said.

Solutions for longevity

Rangeland management is a solution to the region’s woes, Rhodes and his coauthors said.

Converting some areas back to rangeland or improved pastures would encourage the growth of native or perennial grasses to increase soil cover, he said. With their deep root systems and drought tolerance, perennial grasses, along with native grasses, would help the area use less water. Restoring the rangeland would also support the wildlife and environment overall.

“Native plants were adapted to grazing herds of bison that would periodically come through; you could mimic that with livestock grazing,” Rhodes said. “The plants would be adapted to the soil and drought conditions. It also puts more carbon back into the soil; a lot of carbon is currently lost when it gets plowed.”

Rangeland management would also help support pollinators and wildlife, improving the diversity of plant species and wildlife ecosystems. This would improve the overall aesthetics of the area, encouraging more people to get outdoors and improving tourism in the area, Rhodes said.

Rangeland tends to not be considered as suitable for cultivation because people associate the word with more wild or remote places that might not be as productive compared to farmland, he said. The uniqueness of the Great Plains differs though from that mindset.

“There are so many good soils in the area, but I think it kind of gets overlooked because that area is all farmed now,” he said.

Looking ahead, Rhodes is hopeful that researchers working on the Ogallala Aquifer can find solutions to slow down groundwater withdrawals, for the sake of sustaining the region and its residents.