Urban Riparian demonstration site in Seguin approved for three more years

For the past three years, the Urban Riparian and Stream Restoration Program has been conducting research at a demonstration site along Geronimo Creek located within the Irma Lewis Seguin Outdoor Learning Center in Seguin, Texas.

The project, which is funded by a three-year grant cycle through the Clean Water Act nonpoint source grant from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, has been approved for an additional three years’ funding.

The project is a comparison of two moderate to highly erodible stream banks: a restored and a non-restored site.

According to the Urban Riparian and Stream Restoration Program website, the project’s goal is to reduce sedimentation rates and erosion along the stream banks. This can lead to improvements in water quality, in-stream habitat, terrestrial wildlife, aquatic species and overall stream health.

Project partners —including the Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI), the Irma Lewis Seguin Outdoor Learning Center, the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority (GBRA) and the Geronimo and Alligator Creeks Watershed Partnership — have been implementing riparian restoration and bank stabilization techniques at the demonstration site while recording data such as erosion measurements and total suspended solids in the creek.

Picking the right plants

To begin with, the team selected the site where the demonstration project would occur. It needed to have moderate to highly erodible banks. A site along Geronimo Creek was selected in which both sides of the creek are owned by the Irma Lewis Seguin Outdoor Learning Center.

Clare Escamilla, a research associate with TWRI, said the outdoor learning center was excited about hosting the project.

“They bring a lot of school kids there, so doing this type of project keeps in line with what they want going on there,” said Escamilla. “We've been able to work with them and come present to the kids during the summer camp. So it is a good relationship and a natural fit for that location.”

After the site was selected, the restoration could begin.

Escamilla said a key point of restoring the site was selecting which plants to use. “We were looking for natural riparian plants that could handle shade, wetter soils and have good, strong root structures.”

Because of the project’s quick timeline, Escamilla said they went with bare root and potted plants that were already grown.

“We wanted to make sure the plants were going to be able to be grown and established instead of planting them from a seed,” she said. “That did require more intensive labor because we had to dig and put them into the ground, which is where the volunteers came in.”

Read more about the efforts by the team and volunteers to revegetate the stream site in TWRI’s photo essay of a planting day at the urban riparian demonstration site and on the demonstration site webpage under Restoration Demonstration Progress.

Escamilla said her team collaborated with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), as well as some of the local nurseries, to learn what plants were best.

“Since we were not plant experts, we made sure that we were talking with people who understood the area and the goals of the project so that they could recommend the right types of plans that were going to give us that stability and have those strong root structures,” she said.

The Urban Riparian and Stream Restoration Program and Texas Riparian and Stream Ecosystem Education Program conduct trainings throughout the state. The trainings cover an introduction to riparian principles, watershed processes, basic hydrology, erosion/deposition principles, and riparian vegetation, as well as potential causes of degradation and possible resulting impairment(s). Trainings also include information about local resources, including technical assistance, and tools that can be employed to prevent and/or resolve degradation. Instructors are experts from TPWD, U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, Texas A&M Forest Service, Texas A&M Natural Resource Institute, Texas Riparian Association and TWRI.

Setting up for success

After the planting day, the team set up erosion pins along the treatment site and the control site.

The treatment site consists of restored native vegetation along 100 feet of stream bank. Further downstream, there is the 100-foot-long control site, which has been left untreated. The treated and untreated sites are separated by a 100-foot-long buffer area.

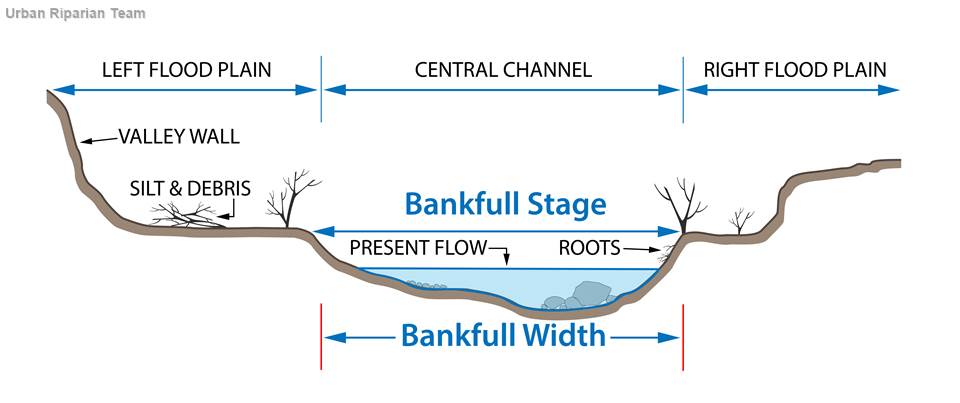

“We set three erosion pins up on both sides of the banks at each of the four cross-sections, so there were 24 pins at each site,” Escamilla said. “We set them up on a bankfull. And then one four feet above bankfull. And then another four feet above that.”

The erosion pins are rebar with the top six inches spray-painted orange. The team hammered in the pins so that only the top six inches — the orange paint — are showing. Escamilla said they went out every three months, or quarter, to see if there was more rebar showing than just those top six inches.

“If there's more of the pin showing underneath the paint, we know that soil has eroded. Then we measure the erosion amount and hammer it back down so that only the top six inches are showing again.”

Closer to the end of the project, Escamilla said they noticed that a few of the pins at the treatment site had less than six inches showing. “Only three inches were showing on some pins, so that soil was actually building up, which is exactly what we want to see.” There was no evidence of these positive results at the control site.

The team also does quarterly photo monitoring, taking pictures at various locations they choose along the stream to compare the changes over time.

Escamilla said part of the photo monitoring includes mapping out where they take the photos along with a description of the locations. In the event of a storm or possible flooding, choosing safe locations along the creek to take photos from is also important.

Photo monitoring can also help document geomorphic changes, which happen over longer periods of time. Examples of geomorphic changes include things like downcutting of the banks and the stream widening from erosion, according to Escamilla. Stormwater can be the cause of many geomorphic changes.

Monitoring, testing and gathering data

After setting up the erosion pins, automated stormwater samplers were installed at the beginning and end of each of the site locations.

The team also does quarterly water quality monitoring, taking grab samples to establish a baseline sediment load in the creek. In the quarterly grab samples and automated stormwater samples, the team measured for total suspended solids to focus on sedimentation and erosion data.

“What we were looking at was how much sediment was coming into the treatment site, and how much was leaving. So was there more sediment that was leaving the system than coming in or less? And then at the control, looking at the same thing,” Escamilla said.

The team checked how much sediment was coming in and how much was leaving the system to see if the vegetation helped to trap some of it and prevent it from entering into the system, so that there was less loading.

“Anytime there was about an inch of runoff, we would have those automated stormwater samplers start collecting so that we could see the amount of sediment that's entering into the creek during those storm events,” said Escamilla. “During these stormwater runoff events, the goal was for the vegetation to reduce erosion and capture excess sediment in runoff and build it up on the banks instead of it entering into the creek.”

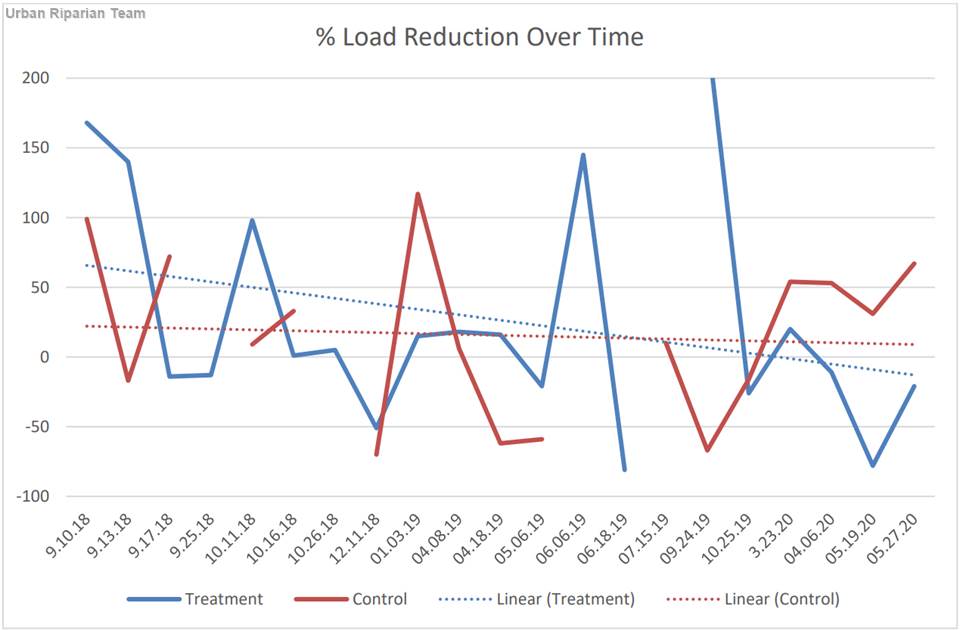

Escamilla said that percent load reduction over time is one of the most significant trends the team observed. The data trend shows that there was less sediment loading in the treatment section than in the controlled segment.

“That’s probably where we started to analytically see an improvement in the stream, that it was trending that there are less loads over time during those storm events, which stayed consistent over the whole project period,” she said.

Another way the team measures erosion and geomorphic changes are by collecting pebble count data and doing cross-section surveys across the stream every year. Learn more about cross-section surveys and the pebble count process via the training videos on TWRI’s Urban Riparian and Stream Restoration Program YouTube playlist.

Looking to the future

According to Escamilla, sedimentation is a common issue in streams and is linked to erosion.

“Too much sediment can build up in the stream and it’s bad for the aquatic species that live in there, but as well, all the sediment that’s going through the stream or river is eventually going to hit maybe a lake or reservoir, and once that faster-moving water hits the lake and it settles, all of that excess sediment floats to the bottom, which eventually starts to build up. So you’re actually reducing that reservoir’s storage capacity.”

Looking at a sustainable water future, Escamilla said it is important to protect Texas water supplies.

“It costs a lot of money to dredge out those reservoirs. In some cases, it’s just as expensive as building a whole new reservoir to remove that excess sediment from the reservoir,” she said. “So finding ways that we can prevent that excessive sediment from getting into the creek will help us be more proactive to prevent some of those other damages downstream.”

Riparian stream restoration can help decrease sedimentation and increase water quantity.

“Having good stream bank vegetation helps slow down floodwaters during flood events, and when it slows down, it allows for groundwater recharge and helps sustain the baseflow,” Escamilla said.

During drier periods where there is not as much rain, there will still be water in the creek, allowing for continued use by wildlife and aquatic species, as well as for recreational purposes.

“This means water is stored on the land and still available during drier months,” she said.

In the next three years of study, the team is hoping to see less loading of sediment over time and less erosion. “We want to continue to see the sediment build up on the treatment section so that during those storm events we’re not getting erosion.”

The team’s bigger picture goal is to show that early restoration efforts can save money and time in the future. Improving vegetation and restoring the stream when the signs of erosion are just beginning to appear allows the stream to be healthy and provide the ecological functions that it was made for.

“We hope to show that our work will be another strategy to help combat some of the effects of urbanization and development that are changing our watershed and also protect the streams that go through those urban areas,” Escamilla said.

Riparian education opportunities

The data and observations gained from this project will be used to demonstrate the benefits of similar restoration projects and in future Urban Stream Processes and Restoration trainings.

The one-day trainings include an indoor classroom presentation and outdoor stream walks.

Upcoming training events include:

- Sept. 7: Riparian & Stream Ecosystem Training - Leon Creek Watershed

- Sept. 22: Riparian & Stream Ecosystem Training - Angelina River Watershed

- Oct. 1: Texas Riparian & Stream Ecosystem Training - Mill Creek Watershed

- Oct. 13: Texas Riparian & Stream Ecosystem Training - Lampasas River

- Oct. 14: Urban Stream Processes & Restoration Training - Mansfield

- Oct. 20: Urban Stream Processes & Restoration Training - West Texas

- Nov. 2: Riparian & Stream Ecosystems Training - Comal River Watershed

- Nov. 5: Urban Stream Processes & Restoration Training - San Antonio

Related trainings by TWRI include:

- Sept. 27-30: Texas Watershed Planning Short Course

- Oct. 25: Stakeholder Facilitation – Working with Stakeholders to Move the Process Forward

- Nov. 11: The Digital Now for Natural Resource Professionals: Online in the 21st Century

For more information or questions, please contact Clare Escamilla at 210-277-0292 x205 or clare.entwistle@ag.tamu.edu.

Subscribe to the Texas Riparian listserv or like them on Facebook for more information on future programs. The riparian education program is managed by the Texas Water Resources Institute, part of Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Texas A&M University.

Explore this Issue

Authors

As a communications specialist for TWRI, Sarah Richardson works with the institute's communications team leading graphic design projects including TWRI News, flyers, brochures, reports, documents and other educational materials.