By Leslie Lee

For many Texans, the Hill Country is not just a region but a way of life: beautiful vistas of rocky hillsides, small towns with live music and quaint festivals, and, of course, hot summer days spent diving into spring-fed swimming holes or floating down iconic rivers.

Those same rivers can tell another story about the Hill Country, however. Those rivers run through Flash Flood Alley, one of the most flood-prone regions on the continent. Following the curve of the Balcones Escarpment through Texas’ middle — from Waco south to Uvalde — Flash Flood Alley’s weather and landscape distinctively work together to produce rapid flood events.

A unique phenomenon

Major flash floods are common along the Balcones Escarpment because of two factors prevalent in the region, according to experts: intense rainfall events and efficient drainage off the landscape.

“The region has some of the highest flood discharge per unit area of a drainage basin in the country,” said Dr. Richard Earl, professor in Texas State University’s Department of Geography. Earl, who joined the department in 1991, has studied flooding hazards for decades and has experienced numerous floods in San Marcos.

High rainfall intensities are common in the region because there’s an infinite source of moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, he said.

Over Texas, these moist, warm air masses from the Gulf collide with cool air masses from the north and moisture flow from the Pacific, said Dr. Nelun Fernando, hydrologist at the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). When warm and cool air masses combine, it results in instability as the warm air rises above the cool air. Additionally, the Balcones Escarpment’s hilly terrain acts as a “ramp” for the fronts and “enhances what was already taking place between the two air masses,” she said.

“The rising air condenses and that creates rainfall,” Fernando said. “That effect gets concentrated over the Balcones Escarpment, and if very slow-moving frontal systems come through, such as what happened with the 2015 Memorial Day storms, then this constant stream of moisture from the Gulf will produce many inches of rainfall over a short period.”

This is called an orographic effect, where a change in elevation causes moisture-laden winds to deflect upwards and cool, resulting in rainfall, said Dr. Robert Mace, TWDB deputy executive administrator for water science and conservation.

“The transition between the Gulf Coastal Plain and the Hill Country is recognized nationally as a place where topographic changes cause these intense, localized floods,” he said.

“In 1921, just on the other side of Austin, 39 inches fell in 24 hours,” Earl said. “In 1935, 22 inches in less than three hours fell near Uvalde. And, in the 1998 flood, one station had 19 inches in 24 hours and a number of stations had 16-18 inches in 24 hours.”

The transition between the Gulf Coastal Plain and the Hill Country is recognized nationally as a place where topographic changes cause these intense, localized floods.

Combined with its propensity for intense rainfall, the region’s rocky topography makes it flood-prone.

“The Hill Country is karst terrain, so it’s limestone that tends to erode in beautiful ways, but along with that beauty you get thin soils, hard surfaces and steep hills, and that all serves to funnel rainfall very quickly into restricted valleys,” Mace said.

Such terrain is created by the Balcones Fault zone, expressed on the surface by the Balcones Escarpment, which “goes through the heart of Texas,” Mace said. Along the escarpment and in areas just north and west of it, almost the entire landscape is sloped.

“It is fluvially dissected, which means that when it rains, the water doesn’t sit there — it runs off into the streams,” Earl said. “That’s hydrologically efficient drainage. When it rains, it just rushes into the streams and you get really intense increases in the amount of flow in the stream.”

Clay-rich soil types in the region are another contributing factor because once they are wet, clay soils have low infiltration and high runoff.

“And, much of the rural landscape is overgrazed,” Earl said. “Combine that with the fact that there’s increased impervious cover around cities and suburban areas — all of these things work together, almost in perfect combination to result in extreme floods.”

A tragic history

Unfortunately, this unique hydrology in Flash Flood Alley has produced a tragic history of flooding events.

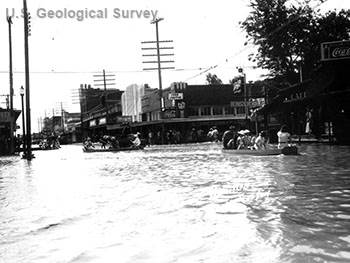

A tropical storm resulted in extreme rainfall in South Texas beginning Sept. 8, 1921, and a wave 12 feet deep flooded downtown San Antonio Sept. 9, killing 51 people. Heavy rains continued, and 38.2 inches of rainfall were recorded from the morning of Sept. 9 to the morning of Sept. 10 in Thrall, northeast of Austin, while 87 people drowned in nearby Taylor.

On Aug. 2, 1978, 27 people died in the Hill Country during flooding caused by Tropical Storm Amelia, when the Guadalupe River at Comfort crested at 40.90 feet, flowing 240,000 cubic feet per second (cfs).

The Shoal Creek Flood on May 24, 1981, was caused by a slow-moving storm directly over Austin; 13 people drowned.

Another terribly perfect storm of conditions led to the Blanco River rapidly rising and raging out of its banks on the Memorial Day weekend in 2015, producing floods that killed 11 people near Wimberley.

All of these things work together, almost in perfect combination to result in extreme floods.

May 2015’s record-setting rains had saturated soils throughout the Hill Country; so when rain began falling Saturday, May 24, most of it ran off, and the Blanco River began to swell.

According to the National Weather Service, at 9 p.m. Saturday the Blanco River at Wimberley was at 5 feet. By 1 a.m. the river was rushing through at 40.3 feet, destroying bridges, homes and lives. The previous record was 33.3 feet.

“The Balcones Escarpment just happens to be at the headwaters of the Blanco, where the landscape has very thin soil and exposed bedrock, so all of that rainfall just goes down the watershed very rapidly,” Fernando said.

“Something that is just mind-boggling is that the discharge at Wimberley during the May 24 storm was more than a fourth of the discharge flow of the Mississippi River at New Orleans, which is about 600,000 (cfs),” Earl said. “And the Blanco’s drainage basin is only 355 square miles, whereas the Mississippi drains almost half of the United States.”

How to plan ahead in Flash Flood Alley

Such tragedies highlight the importance of residents actively monitoring conditions, just as the region’s long history of flooding catastrophes demonstrates a need for continued improvements in flood planning and management, the experts said. Residents and decision-makers alike can help mitigate future disasters.

In 2015, Gov. Greg Abbott transferred $6.8 million to TWDB from the Disaster Contingency Account to provide additional technical assistance and outreach for floodplain management and planning and to develop a high-tech network of stream gauges. As part of that $6.8 million, TWDB issued a $2 million request for communities to apply for grants to implement early warning systems or develop flood response measures.

The governor’s funding initiative has also paid for additional stream gauges installed throughout Central Texas in the past year, including on the Blanco.

Residents are increasingly signing up for flash flood warnings and emergency notifications to be sent to their cell phones, sometimes referred to as “reverse 911,” which is one positive effect of recent floods, Earl said.

“Those changes are sort of the good news,” Earl said. “The bad news is that the local decision-makers have been reluctant to say no to developers.”

Various scientific definitions affect how municipalities’ city planning officials balance development with flood safety.

Floodplain designations are affected by 100-year storm rainfall levels, and floodplains are a major part of city planning. For Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood insurance purposes, official FEMA maps define 100-year floodplains, also known as areas that have a 1-percent chance of flooding in any given year.

Those changes are sort of the good news. The bad news is that the local decision-makers have been reluctant to say no to developers.

For planning purposes, cities sometimes define their own floodplains. “Cities might choose to plan for a new 100-year floodplain that isn’t yet accepted by FEMA or plan for greater floodplains,” Mace said.

“Many cities around here use 10-11 inches in 24 hours as the ‘100-year storm,’” Earl said. “However, a climatologist in the department and I did a study after the 2002 flood, and we concluded that the 100-year storm or 1-percent probability storm should be defined as more like 12-13 inches. What that means is you have to make floodplains bigger, and therefore that’s less land that can be developed.”

Integrating retention and detention ponds into developments, using floodplains for green space or parks that will hold and spread out water during floods, and limiting impervious cover are some planning strategies that can reduce flooding.

Building developments in floodplains on top of man-made taller pads or foundations might appear to be a flooding solution, Earl said, but this practice can actually cause flooding to be worse in adjacent neighborhoods and areas.

San Marcos, Austin and many other cities in the Interstate-35 corridor are facing the need to balance rapid population growth with sustainable development. For the last three years, San Marcos was the fastest growing city in the United States.

“I would recommend that, first, areas that have been previously flooded should not have new development,” Earl said. “And second, there should be floodplain noticing requirements for both owner-occupied and rental properties. Presently, I do not believe that property owners are required to notify renters that they’re renting a place in a floodplain.”

Mace urged Flash Flood Alley residents to get educated about local flooding risks, sign up for automated weather warnings sent to cell phones, consider purchasing a National Weather Service radio and read about flood preparation on texasflood.org, a site TWDB developed in 2016 with state funds.

“We have a saying here: ‘everybody lives in a floodplain,’” he said. “Even local circumstances can cause flooding. There’s always a chance."