By Leslie Lee

The Houston Ship Channel is a huge part of the Texas and national economy. Its 52 miles of winding waterways are lined with industrial terminals and plants, providing an enormous amount of jobs for the region.

Families also live, work and play in neighborhoods along the ship channel.

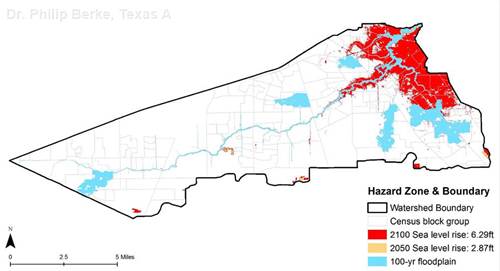

Southeast of downtown Houston, Harrisburg-Manchester is one such neighborhood. The flood-prone, under-resourced community is bordered by industrial plants, Sims Bayou and the ship channel, with Loop 610 crossing through its center. Its stormwater should drain into the Sims Bayou Watershed, but average rainfall often results in large pools and ponds held in the streets for much of the year.

Flooding threats from multiple causes — sea level rise, inland flooding and coastal flooding — are a reality for much of the region around Houston. But in Harrisburg-Manchester, where the infrastructure already cannot handle even a normal rainfall event, Texas A&M University experts have found these threats to be especially serious.

“The neighborhood faces average flooding on a regular basis, because the stormwater infrastructure just doesn’t work well,” said Dr. Philip Berke, director of the Institute of Sustainable Coastal Communities, part of the Texas A&M College of Architecture and Texas A&M University at Galveston. “And at just a moderate projection of sea level rise, the neighborhood will be significantly impacted; so what is a small flood now will be even worse in the future. The infrastructure that’s already not working there will not be sufficient.”

To help Harrisburg-Manchester deal with current environmental risks and prepare for future challenges, Berke and a team of Texas A&M experts from various academic disciplines have helped create a partnership with the community. The Resilience and Climate Change Cooperative Project (RCCCP) is housed under the institute and is a multiyear, interdisciplinary, collaborative research and engagement venture with residents of Harrisburg-Manchester, as well as other neighborhoods and communities in Texas.

And at just a moderate projection of sea level rise, the neighborhood will be significantly impacted; so what is a small flood now will be even worse in the future. The infrastructure that’s already not working there will not be sufficient.

RCCCP combines university research, community engagement and service learning opportunities, which involve Texas A&M students in applied-research classes studying and addressing real problems for the neighborhood. About 20 faculty members, 10 graduate students and 30 undergraduate students are working on RCCCP efforts. Berke, RCCCP principal investigator, spoke to txH2O on behalf of the many projects, teams and individuals that make up RCCCP.

Berke came to Texas A&M in 2014 specifically for the opportunity to begin a program connecting university research with an under-served community.

“Texas A&M allowed me to do something I’d wanted to do for a very long time,” he said.

So far the research has addressed water quality, stormwater infrastructure, reliability of citizen scientist data and more.

The project has been such a success that Texas A&M has made it the university-wide Environmental Grand Challenge, part of the Provost’s Grand Challenges program that tackles big societal problems through academic research and outreach.

Listening to locals’ experiences

The cooperative began with the guidance of Texas Target Communities (TTC), a program within the architecture college that “has a long history of successfully serving under-served communities,” Berke said. “TTC understands that when we’re engaging communities where there is distrust, you have to build trust.”

A team of Texas A&M experts arranged listening events with community leaders, interest groups and Harrisburg-Manchester residents so that their concerns, personal experiences, observations and informal data could inform the research moving forward. These events also create a line of communication for research results to be better implemented, Berke said.

“We could do technical analysis and research, and then just throw that data over the fence, or we can work with them, listen to the issues and try to match the science and research that we do to serve the real issues.”

At least eight research projects resulted from the initial meetings with the community in the spring of 2015; the partnership flourished and the RCCCP team at Texas A&M grew, Berke said. For the last two years the team has met every other week over lunch to continue collaborating on the projects and updating each other on ongoing work.

We could do technical analysis and research, and then just throw that data over the fence, or we can work with them, listen to the issues and try to match the science and research that we do to serve the real issues.

The RCCCP team is made up of faculty and graduate students from Texas A&M’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, Department of Civil Engineering, Department of Geography, School of Public Health, Department of Sociology and the Bush School of Government and Public Service, as well as the Department of Sociology at Louisiana State University.

The team collaborates with TTC, as well as the organization Texas Environmental Justice Advisory Services (TEJAS), which was founded in Harrisburg-Manchester, is still officed there and now does statewide advocacy. The TEJAS groups’ experience and relationships in Harrisburg- Manchester made it possible for RCCCP to begin to build relationships with the community, Berke said. He said that TEJAS deserves much of the credit for the cooperative’s success.

“We didn’t just walk into the neighborhood,” he said. “We’re doing science, but we’re also delivering the science in a way that is framed based on how the community defines their needs and concerns.”

Equipping students with science

A key part of RCCCP’s community-led work has been collaborating with a group of Furr High School students who have been incredibly helpful to the community, Berke said. He credited much of RCCCP’s collaborative success to the leadership and teachers at Furr, which is part of the Houston Independent School District. RCCCP has worked with the Green Institute at Furr, which includes the Green Ambassador Woodsy Owl Conservation Corps, sponsored by the U.S. Forest Service.

“The Green Ambassadors are 30 amazing students,” he said. “These students are really the core of the participatory-based research in the neighborhood. They have participated with locating and identifying pooled water locations, applied and tested an infrastructure assessment tool, and assisted in collecting health and perceptions data by administering door-to-door surveys.”

Funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant, a RCCCP team recently began working with the Green Ambassadors to use cell phone applications to measure and track infrastructure and water quality issues in the neighborhood, building on previous infrastructure assessment efforts by Furr students.

Ponding and pooling are types of flooding that aren’t always tracked by official agencies, so this data could better equip local authorities in addressing Harrisburg-Manchester’s infrastructure needs, he said.

“Our group from civil engineering, public health and urban planning is running this project to test the validity of the data that’s being collected on local infrastructure in the neighborhood against expert-driven data collection, which is much more expensive,” Berke said.

The NSF-funded project will run for three years, and it has already included trips to Texas A&M for the students to experience university life for themselves, Berke said. David Salazar, one of Furr’s science teachers, is so invested in RCCCP’s work that he recently began graduate school in Texas A&M’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning.

“He is a great role model for the neighborhood, and we hope to continue recruiting undergraduate and graduate students from there,” Berke said.

Examining water quality

RCCCP scientists initially collected water quality data in Harrisburg-Manchester.

“The reason our team chose to study surface water quality there was that the residents mentioned the flooding issues, and they were worried about polluted water and effects of being in contact with it,” Berke said.

Air quality and water quality were both frequently discussed at the community meetings RCCCP held as well as in a door-to-door public health survey the RCCCP researchers conducted, he said.

RCCCP’s surface water quality study was conducted by faculty and graduate student researchers in the School of Public Health. They began by splitting the neighborhood into 30 zones and then taking one surface water sample in each zone, Berke said. The samples were tested for arsenic, barium, chromium, lead and mercury, along with other heavy metals.

“Our researchers found that a few of the samples had very elevated levels of arsenic, barium, chromium, lead and mercury,” he said.

Barium, which is used in many refinery processes and products, was found in every zone.

“Worrisomely high” lead levels were found in standing water about two blocks away from Harrisburg-Manchester’s main park, Berke said. The study’s findings have recently been published in a public health journal.

An upcoming RCCCP study will examine drinking-water quality in the neighborhood.

The causes of environmental vulnerability in Harrisburg-Manchester are multifaceted, he said.

“There’s poor water quality and poor air quality,” he said. “They have stressed relationships with nearby industry. The infrastructure is poor. The neighborhood has very narrow streets, but huge industrial 18-wheelers are driving through all the time.”

Facing long-term risks, together

Although the individual research projects will be completed in a few years, the RCCCP team is committed to engaging and serving in Harrisburg- Manchester long-term.

“A key core principle that we’re going to follow is: we’re sticking with these neighborhoods for the long haul,” Berke said. “And we’ll begin working with other under-served neighborhoods to continue this work, including the Sunnyside neighborhood.”

One reason this committed approach is important is that the flooding and infrastructure problems are projected to only get worse.

In the Sims Bayou Watershed, 26,180 people live in the 100-year floodplain. According to RCCCP data, if moderate projections of sea level rise happen, the watershed’s floodplain would then include 35,354 people, and that’s not even accounting for likely population growth.

Moving forward, RCCCP is going to continue building its team’s research capacity, while helping Harrisburg-Manchester’s residents build theirs. This includes educating the community on local flooding and its causes, including development and increased impervious surfaces in the Sims Bayou Watershed.

According to RCCCP research, development was shown to grow by 10 percent from 1980 to 2000, which led to increases in streamflow within Sims Bayou and a 15 percent larger flooding area.

Educating local and regional decision-makers on these approaching risks as well as the current insufficiencies in the neighborhood’s infrastructure is one area of work RCCCP will continue to expand, Berke said. They want to inform policymakers about the challenges facing Harrisburg-Manchester’s residents.

“Someone has to look at the broader policies affecting these people,” he said. “They need to account for them. They have been under-served for decades.”