Operating a reservoir in Texas requires managing an extensive list of fluctuating variables: stream flows, scheduled withdrawals, rainfall, evaporation rates, stormwater runoff, municipal water demand, fisheries, recreational needs, water quality, flooding, invasive species and more. Operators all over the state use various forecast models to juggle surface water management amid these sometimes difficult-to-predict variables.

Forecast-informed reservoir operations, or FIRO, is a water supply management strategy recently adopted in the western U.S.

Using FIRO, reservoir operators look to robust, reliable forecast models and manage reservoir releases differently than traditional protocols. For example, if a drought is approaching, they may save more water in the lake’s flood pool than usual, and if a major flood event is coming, they may release water preemptively.

But, those operations involve numerous factors, including fulfilling all obligations to downstream customers and water users. Reservoir operators would work closely with water supply entities to implement the most efficient and low-risk operations.

FIRO management strategies could greatly benefit Texas water supplies, but implementing them is not as simple in Texas.

Understanding Texas’ reservoirs

Max Strickler has managed federal reservoirs in Texas for over 10 years and knows many of those lakes inside and out. As a water management lead engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) – Fort Worth District, he supervises reservoir operations for 25 reservoirs across Texas, and each is a balancing act.

“These are multipurpose reservoirs, primarily built for flood risk management, but they also have other purposes such as water supply, fish and wildlife, environmental and recreation,” he said.

FIRO offers the potential to help ensure water availability during periods of drought in a cost-effective way.

Estimate reading time: 7 minutes

Implementing forecast-informed reservoir operations is difficult in Texas, but scientists are working to change that

More Information

- Pilot project aims to improve reservoir operations in Texas, Texas Water Development Board

- Evaluating Enhanced Reservoir Evaporation Losses From CMIP6-Based Future Projections in the Contiguous United States, Earth’s Future, Vol. 11, Issue 3

- Reservoir Evaporation Tool, Texas Water Development Board

- New study reveals global reservoirs are becoming emptier, Texas A&M Engineering

- California’s Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations Are Key to Managing Floods and Water Supplies, California Department of Water Resources

Want to get txH20 delivered right to your inbox? Click to subscribe.

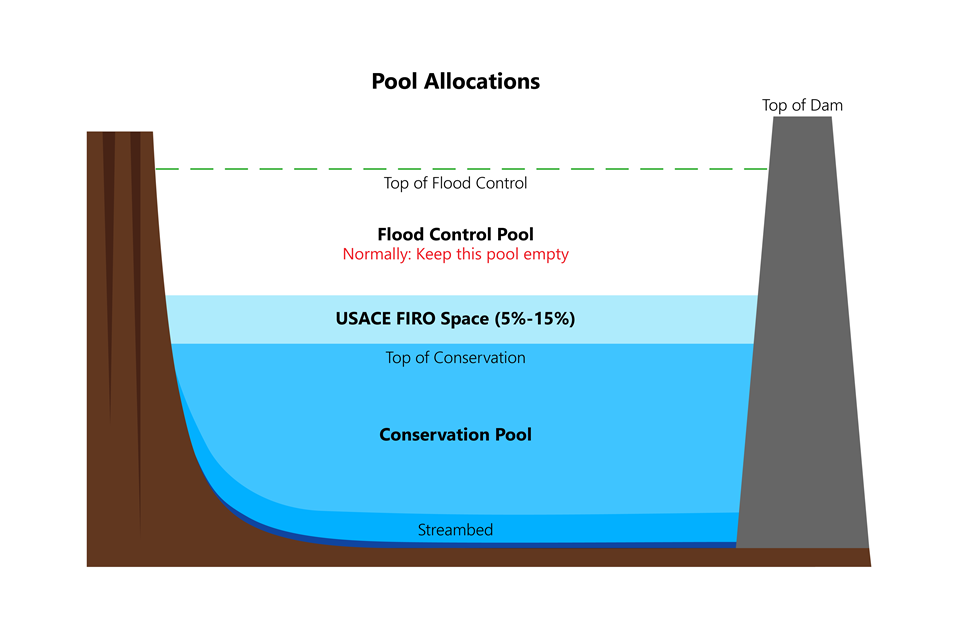

Strickler explained that the philosophy of the flood pool, which is where operators capture flood waters, is that it should be as empty as possible to always be prepared for the next flood (see diagram on page 15). “That is in competition with the philosophy behind the conservation pool or water supply pool, which says that it should always be as full as possible to prepare for the next drought,” he said.

“If you can safely increase the amount of water being held temporarily in the flood control pool, you are able to increase supply temporarily,” stated Nelun Fernando, Ph.D., manager of the water availability program at the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) in a news release. “FIRO offers the potential to help ensure water availability during periods of drought in a cost-effective way.”

In years past, precisely measuring evaporation rates and accurately forecasting floods and droughts in Texas has been extremely difficult. While government agencies publish improved forecast products all the time, verifying their accuracy to make real-world operational decisions is a challenge, Strickler said. Texas operators also face infrastructure constraints, rapid population growth, environmental concerns and real estate development in floodplains.

Whitney Lake Dam Gates (south side). Photo by Trevor Welsh, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Could FIRO work in Texas?

“California in particular has had recent success with FIRO because of the high accuracy of the precipitation forecasts in that region,” Strickler said. “Significant investments in meteorological research likely need to happen in Texas before the widespread adoption of FIRO by reservoir operators. Amounts, location and intensity of precipitation are all critical aspects of FIRO that need to see improvement in Texas over the coming years.”

The unpredictability of Texas’ weather makes FIRO simultaneously difficult and badly needed. “We always have to be prepared for floods or drought,” he said.

Experts tout the benefits of FIRO, such as: making more water available without costly infrastructure investment, storing flood water in late spring and early summer, reducing the need for pumping by utilizing natural flows instead and storing runoff during consecutive drought years.

And now, as forecasts and technology improve, Texas operators are beginning to trial-run FIRO.

Since the summer of 2022, TWDB has partnered with the University of Texas at Arlington, USACE Fort Worth, the National Weather Service West Gulf River Forecast Center and the Brazos River Authority on a FIRO pilot project in the Little River watershed in the Brazos River basin.

Funded by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the project is studying how short-term operational changes to Lake Georgetown’s flood pool can be implemented using improved rainfall forecasts.

Getting the evaporation variable correct

One key piece of the FIRO puzzle is evaporation rates.

Evaporation loss from reservoirs is a major variable for Texas water planners to incorporate into strategic reservoir operations and models. Using reservoir system simulation models will be one of the first steps that Strickler and other water managers will take toward FIRO. Utilizing the models, they can run hundreds of different hypothetical lake operation plans to find which work best in Texas and then hopefully implement them in the real world.

I think people would be shocked at how much evaporates. In Texas, daily evaporation is about the same as daily water supply use.

An expert in reservoir evaporation, Huilin Gao, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Zachry Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Texas A&M University who researches hydrological modeling, remote sensing, water resources management and evaporation rate modeling for informing FIRO.

Remarkably, reservoir water lost via evaporation is substantial — not just in Texas but around the world.

“A recent research study showed that over the last few decades, globally, reservoir evaporation losses actually exceed the total industrial and domestic water consumption together,” Gao said.

“I think people would be shocked at how much evaporates,” Strickler said. “In Texas, daily evaporation is about the same as daily water supply use.”

Gao and collaborators published their research in March laying out just how much evaporation may tax U.S. reservoirs in the future, exacerbated by climate change impacts.

What they discovered was significant.

“Reservoir evaporation losses in the United States are projected to increase by 2.5×107 m3 per year under the highest future warming scenario,” she said.

Somerville Lake. Photo by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – Fort Worth.

Proctor Lake Dam by Trevor Welsh, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – Fort Worth.

The research team projected the future evaporation rate and losses with the Lake Evaporation Model, developed by Gao’s lab, under a commonly adopted representative future climate scenario. For 678 major reservoirs across the United States, both evaporation rates and losses are projected to increase. She said that future exacerbation of evaporation will be much more substantial in the southwestern United States and is expected to be more severe in the fall.

“Water planners need to consider accelerated water loss through open water evaporation in long-term water resources planning across various spatiotemporal scales,” Gao said.

To help water planners do just that, her research team, in collaboration with the Desert Research Institute, also recently produced a critically needed new product — the Reservoir Evaporation Tool website, which will be in TWDB’s suite of online tools.

Previous evaporation tools in Texas used monthly data interpolated from the A-pan observations. A-pans are physical evaporation measurement tools, usually located in small metal tanks near a reservoir, but sometimes miles away. A-pans cannot accurately represent all reservoir characteristics, such as location, area and depth.

In contrast, Gao’s new site provides both daily and monthly evaporation for each of Texas’ 188 large reservoirs, from 1980 to the present. And, it offers the option of monitoring smaller lakes by inputting a custom reservoir scenario. It was co-funded by TWDB, USACE Fort Worth and the Lower Colorado River Authority.

Strickler said that this new evaporation data is going to be critical to FIRO pilot projects in Texas. Using this modern data, FIRO strategies can help Texans save water and money.

“It’s billions of dollars to build new lakes and dams,” he said. “In contrast, the great thing about FIRO is, it uses the expensive dams and lakes we already have, but uses technology to make them more efficient and beneficial.

“FIRO will be much cheaper per acre-foot of water than doing more dam building.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As communications manager, Leslie Lee leads TWRI's communications and marketing strategy and team, manages TWRI's publications, and coordinates effective communications support for TWRI's numerous projects serving the state of Texas.