The Texas coast is known for its seven major bays and five minor estuaries that boast incredibly diverse wildlife and aquatic species and draw tourists from around the country. From popular swim spots like Galveston Bay to world-renowned fishing destinations like Baffin Bay, the variety and beauty of Texas bays have long been known.

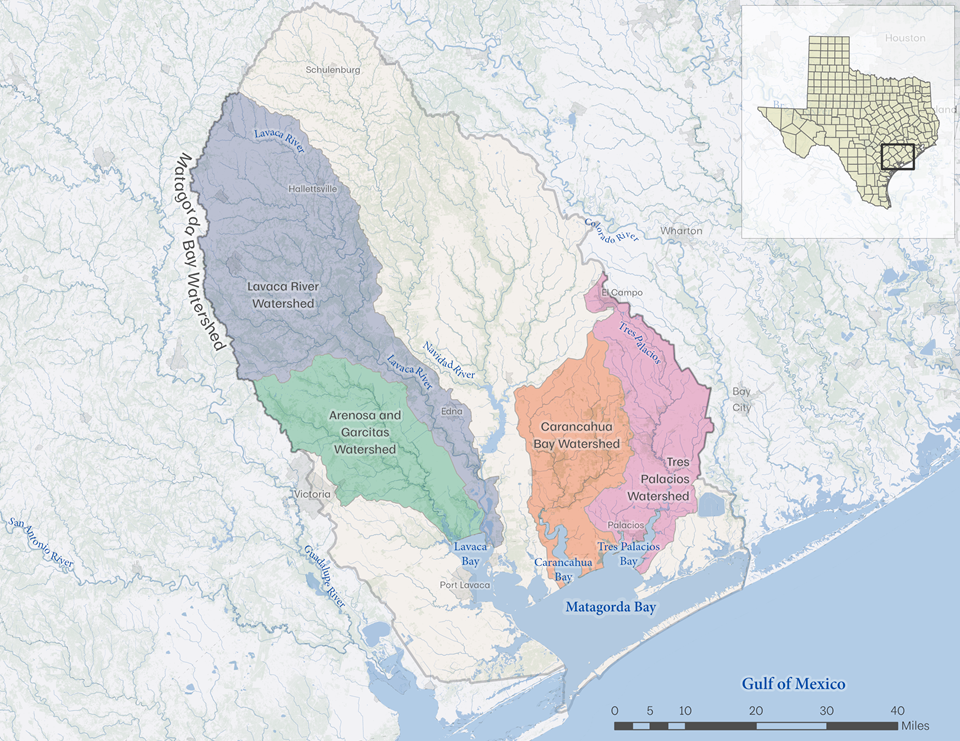

Tucked in the middle of the Texas coast is Matagorda Bay. Near Victoria, the bay is a minor estuary, smaller when compared to some of the more well-known bays. Matagorda Bay itself is not highly developed and is fed by various creeks and rivers: Arenosa Creek, Tres Palacios Creek, Garcitas Creek, Carancahua Creek and the Lavaca River.

“The primary industry is agriculture and depending on where you’re at, could be rice, could be aquaculture, could be turfgrass, and then obviously row crops,” said Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI) Interim Director Allen Berthold, Ph.D. “Another one is beef cattle. There’s a lot of wildlife, so it’s a popular hunting area as well as other ecotourism sources of revenue from fishing and beachgoers.”

There is also some influence on the bay from oil- and gas-related industries.

Water testing in recent decades has found Matagorda Bay impaired with elevated bacteria levels, and many of the contaminants have come from the river and creeks that feed the bay.

“Bacteria comes from the excrement of everything with hair, fur and feathers,” said TWRI Associate Director Lucas Gregory, Ph.D. “So, it’s literally everywhere across the watershed. But those in-stream numbers don’t meet the state’s water quality standards, which are in place to protect human health or at least act as a shield from that level of risk.”

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

Water researchers explain how four watersheds impact a basin

More Information

Want to get txH20 delivered right to your inbox? Click to subscribe.

Taking a basin-wide approach

TWRI first became involved with the Matagorda basin in 2014. “Because there were multiple bacteria impairments, we decided to collect and analyze all of the existing data within the entire basin before jumping into a single watershed,” Berthold said. “We thought, maybe we can maximize our time this way, especially since everything is in the same area.”

Funded by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), the Matagorda Bay Basin project soon began.

“The goal with a watershed protection plan is to define management recommendations and strategies that can be implemented to reduce some of those bacteria concentrations and other concerns over time.Lucas Gregory, Ph.D.

The project’s first year involved data collection, data analysis and other activities such as developing maps of septic system locations. TWRI also worked with local stakeholders, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service county agents, and nearby soil and water conservation districts to form relationships and eventually bring in educational programs.

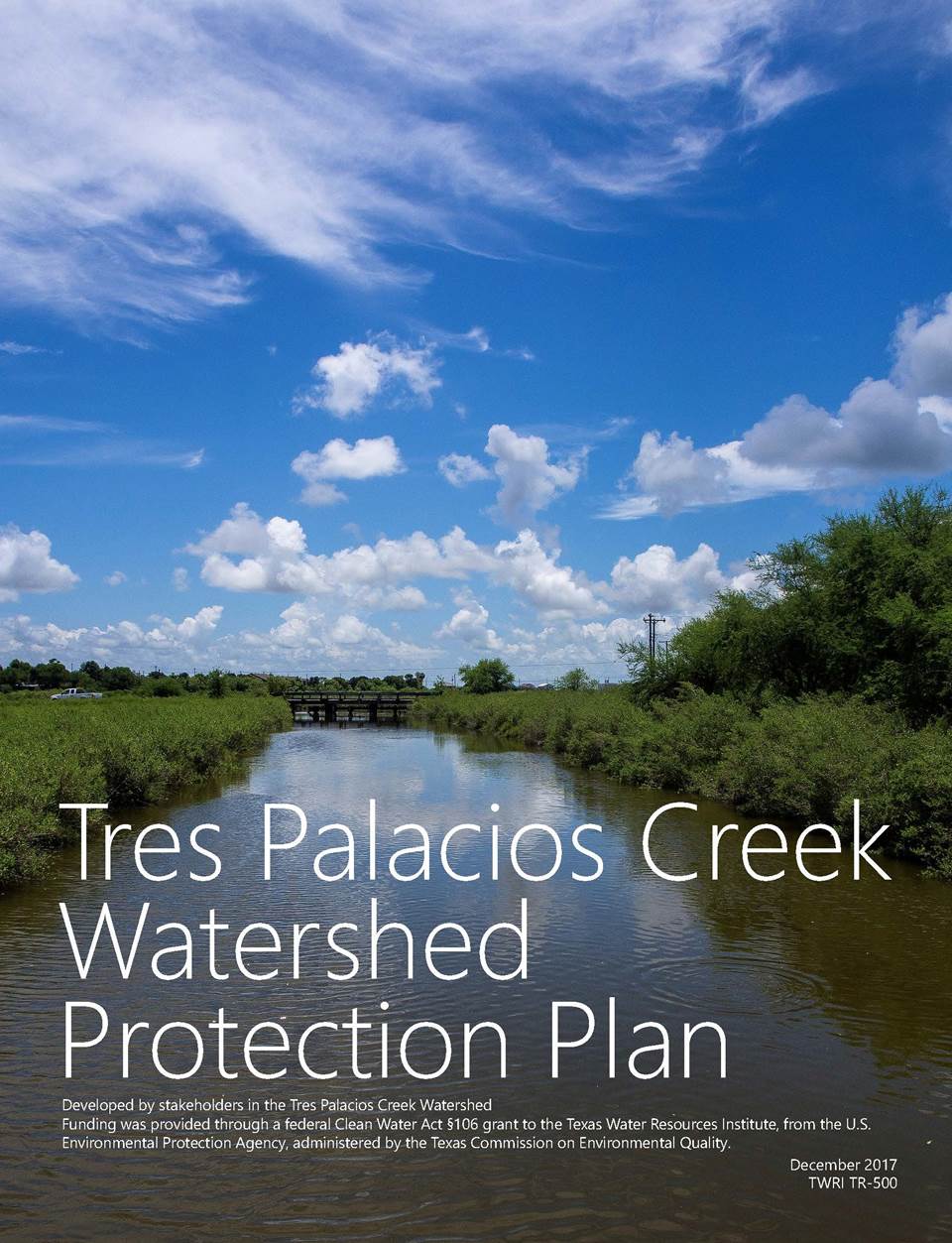

The team began working with local stakeholders to develop watershed protection plans (WPPs) for watersheds in the Matagorda Bay Basin, and the first was published in 2017: the Tres Palacios Creek WPP.

Water quality monitoring done through the Clean Rivers Program, managed by TCEQ, had found that fecal bacteria levels in Tres Palacios Creek were often exceeding the state’s recreational water quality standard. Additionally, dissolved oxygen (DO) monitoring within a 24-hour period found DO levels below the state’s standards.

“The goal with a watershed protection plan is to define management recommendations and strategies that can be implemented to reduce some of those bacteria concentrations and other concerns over time,” Gregory said.

Helping homeowners shore-up septic systems

TWRI currently works with local communities to develop stormwater management resources that homeowners can implement to ease their impact on the creeks and ultimately, the bay.

Septic systems have been identified as an issue in the area; failing systems near the creek create major health concerns and have been identified as a priority to address potential bacterial load.

“There’s a couple of mobile home communities that are right on the shores of the bay,” Gregory said. “Based on the results of the project, there was quite a need to address some of those families’ septic systems.”

This has included both educational outreach efforts to increase awareness about proper septic operation and maintenance, along with septic system repair or replacement programs when necessary.

Making progress in more watersheds

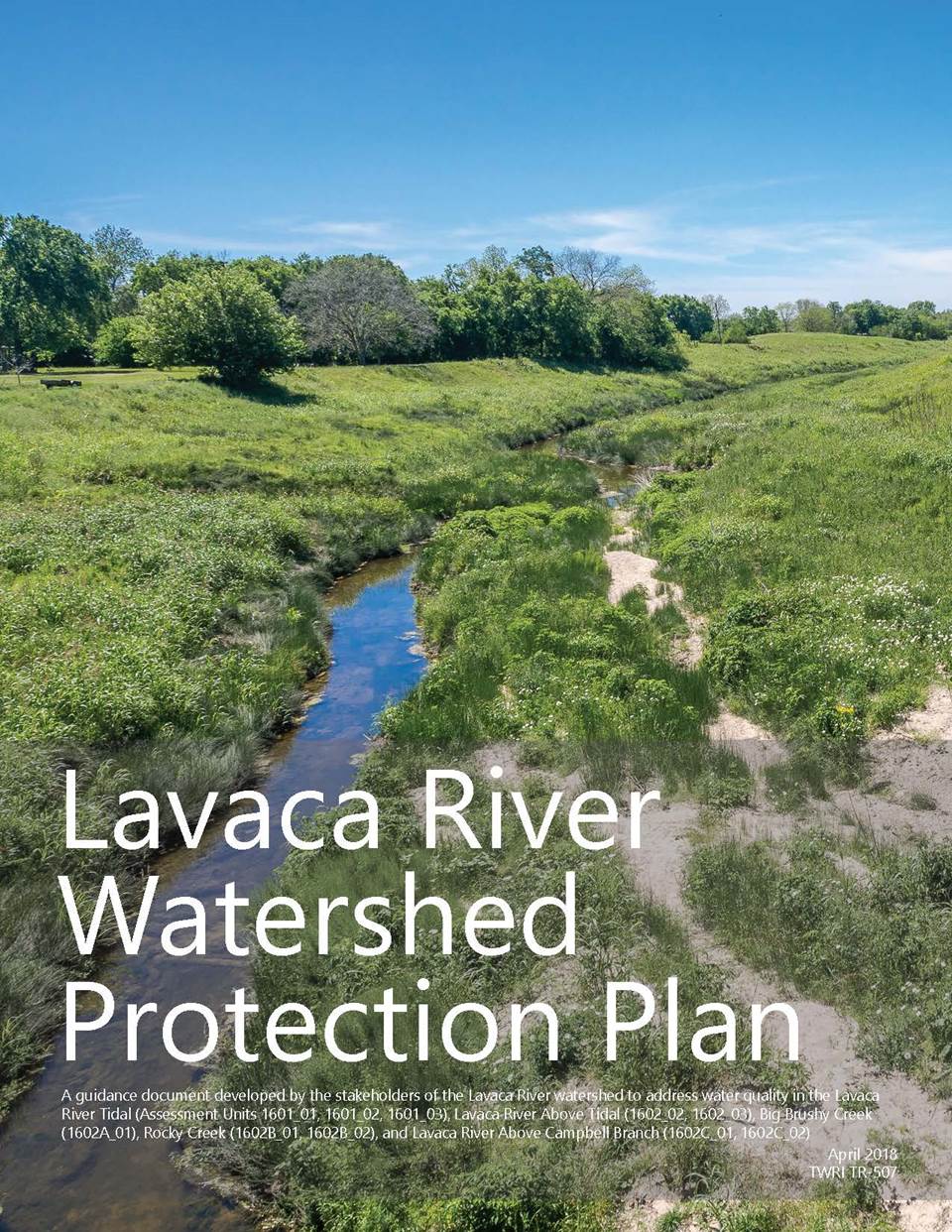

The next WPP came in 2018 for the Lavaca River. Citing excessive E. coli levels and depressed DO, sections of the river had exceeded TCEQ water quality standards for human contact since 2008.

“Our Lavaca implementation project was pretty similar to the Tres Palacios implementation project: public education, stakeholder meetings and water quality monitoring,” Berthold said. “We actually partnered with the Lavaca-Navidad River Authority, and they did the water quality monitoring on that project.”

Everybody’s downstream from somewhere, and what happens upstream affects those downstream. If you’re a good steward in your area, it helps those further downstream.Chad Kinsfather

Chad Kinsfather, director of environmental services at Lavaca-Navidad River Authority (LNRA), is involved with work upstream from Matagorda Bay.

“Everybody’s downstream from somewhere, and what happens upstream affects those downstream,” Kinsfather said. “If you’re a good steward in your area, it helps those further downstream.”

LNRA works with local stakeholders to address watershed concerns and create discussions about better management practices that can help lessen pollution downstream. They also create educational programs for youth to help the next generation understand why protecting water quality matters so much.

Kinsfather noted the high levels of bacteria within the watersheds, which is an issue also highlighted in WPPs and research. While that pollution can come from wildlife, which can’t be controlled, livestock in the area are also contributors. LNRA works with other agencies to educate farmers and ranchers about these problems and the resources available to them to lessen their environmental impact.

“Each individual landowner has their own, literal watershed that they’re responsible for, and it’s very important that they understand this from a river authority perspective,” Kinsfather said. “I can’t tell you what to do and that’s a great source for water, but cows are a great source of pollution and bacteria. It’s a very real health standard risk.”

Port Lavaca. Photo by Cameron Castilaw, TWRI.

Working towards a healthy Matagorda Bay

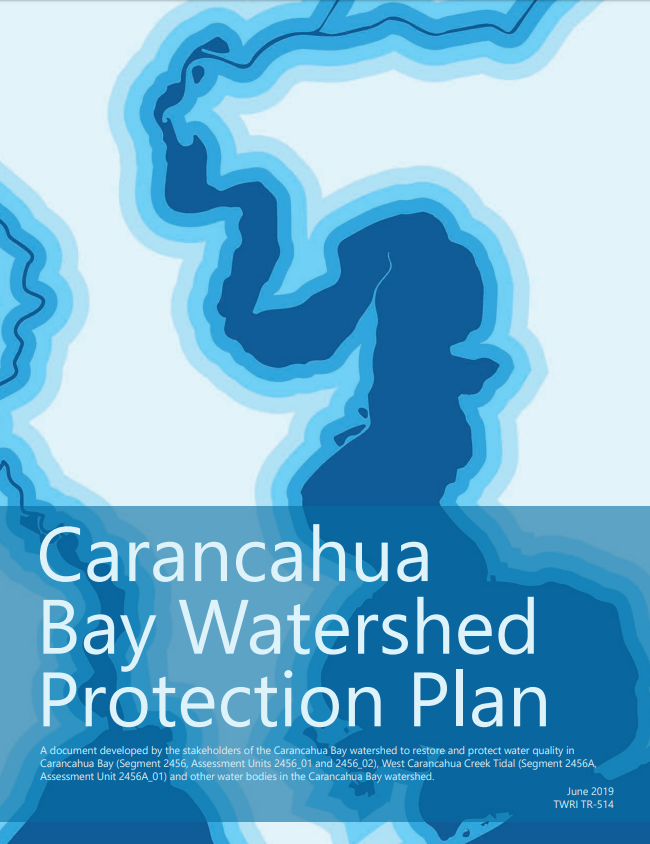

TWRI is also working on WPPs for other creeks within the bay system; a lack of information and data had been a roadblock for those plans to be accepted. There are ongoing efforts to fill that gap.

One such way is led by Steven Raabe, the trustee for the Matagorda Bay Mitigation Trust. The trust was created from a Consent Decree in 2019 as part of a lawsuit between the San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper and Formosa Plastics Corp. Raabe oversees distributing funds from the lawsuit for projects ranging from environmental education to restoration work along Matagorda Bay. Since its creation, the trust has executed 47 different contracts within the bay area, totaling $17.5 million worth of work.

“The bay is a significant economic generator for this area of the coastal band, both from a recreational standpoint and commercial fisheries,” Raabe said. “So, the projects that we’ve been working on support both of those objectives.”

The trust recently finished its first major project since its creation three and half years ago, the Shaky Point Living Shoreline Restoration. Project timelines tend to take longer in sensitive environmental areas such as the bay, Raabe explained, due to environmental permits and the need to get local stakeholders involved.

Matagorda Bay has a very significant industrial economy. While it’s very important to the area, particularly from the standpoint of providing jobs, it’s also important that the industries care for the environment.Steven Raabe

Studies from Texas A&M University at Corpus Christi and Galveston and the University of Texas Marine Science Institute have also received funding to provide environmental research that can be used for future projects.

“Those studies are bringing a lot more scientific information about the bays that stakeholders can use,” Rabbe said. “They want to develop projects because this area doesn’t have a lot of scientific information available; we’re trying to correct that.”

One area that the trust focuses on is mitigating environmental harm caused as a side effect of industries operating in or near the bay area, he said. Plastic pollution has been a problem in the past, with funding going towards clean-up efforts and restoration work.

“Matagorda Bay has a very significant industrial economy,” Raabe said. “While it’s very important to the area, particularly from the standpoint of providing jobs, it’s also important that the industries care for the environment.”

All parties involved understand people’s hesitance to get involved in restoration efforts when they feel that they are being blamed for the issues, Berthold said.

“Ag is going to point at urban and urban is going to point at ag,” he said. “However, there’s no single problem; it’s cumulative, it’s an issue that we’ve got to address as a whole, so everybody’s got to do their part.”

Another factor to note, Berthold said, is that wildlife and their impact cannot be measured in an accurate way. That is something to keep in mind when understanding all factors impacting the bay area.

There are simple ways for landowners to lessen their environmental impact he said, such as being cognizant of not overgrazing. This allows for better water infiltration with improved grass and root systems, which ultimately means less runoff of byproducts from humans and animals. Regular septic system maintenance is another way to reduce potential impact to waterways.

“Just because it’s out of sight does not mean it should be out of mind,” Berthold said.

By providing resources and education for best practices aimed to protect the waterways, Berthold and others involved hope to make a lasting impact that ultimately results in returning Matagorda Bay and the water bodies that are part of it to healthy and safe levels.

While there’s no set way to ensure this, continuing efforts and the participation of local stakeholders provide a glimpse of what could be reality.

“The long-term goal is to improve and protect water quality to maintain the various economies and ecosystems that rely on it,” Berthold said. “And we achieve that by everyone doing their part.”