Water scientist by profession, humorist by choice

To hear Dr. Robert Mace speak at a water conference is to hear a very knowledgeable water expert mixing in a little humor on the side.

Determined to retain the interest of the audience, many times Mace titles his presentations with humorous names, such as “Gone With the Wind: The History of Pumping Water With Windmills” and “Mace’s Believe It or Not: Bizarre Texas Groundwater facts!” and inserts humorous quips in the talks.

Even though the new chief water policy officer and associate director for the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment calls himself an “available goofball,” he is an accomplished and respected water scientist serious about the future of Texas water.

A new venture

Joining the Meadows Center in December 2017 after an 18-year career with the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), Mace is responsible for integrating science into the development and assessment of policy.

The Meadows Center, part of Texas State University, focuses on developing and promoting programs and techniques dedicated to ensuring sustainable water resources for human needs, ecosystem health and economic development, according to its website.

Dr. Robert Mace said his goal is to use his experience to help other scientists be more effective in getting their science heard by policymakers and by the public. In his position at the Meadows Center, Mace will draw on his experience, knowledge and even his witty personality to continue to make an impact on Texas water.

More information

Listen to Dr. Robert Mace's : GIS (is more fun than beer)

“This position seemed rather perfect for me because I had worked at a state agency with a lot of interaction with the Texas Legislature, which gave me a front-row seat on seeing how to effectively employ science in the policy world,” he said.

His background at the board also gave him experience in a wide range of water issues.

“In my career at the board, I touched on nearly everything related to water — water conservation, groundwater modeling, groundwater management issues, environmental flows, desalination, floods, what causes drought — all those things are intertwined when you talk about water in the policy world,” he said.

At the Meadows Center, Mace said his goal is to use his experience to help other scientists be more effective in getting their science heard by policymakers and by the public.

“Often scientists have their hearts in the right place to bring science to the real world and to the policymakers and decision-makers,” he said, “but they are talking way over the heads of the people they are trying to communicate to, which means they are not communicating.”

He said although he will not be writing or advocating water policy, he hopes to provide analysis of policies and how they intersect with science.

For example, depending on how a certain policy is put in place, Mace said it could have unintended consequences that policymakers might not be aware of.

“Policymakers need to know the potential impacts of these decisions,” he said.

With a joint appointment as a professor of practice in Texas State’s Department of Geography, Mace said he hopes to extend this understanding of the interconnection of science and policy to students.

“I want to be able to help prepare students for working as scientists not only in the working world but also in the policy world, by giving them a practical understanding of how the policy world works,” he said.

Water scientist by profession, humorist by choice

Rocks + math = water

Growing up in rural northwestern Illinois near the Mississippi River, Mace had many, varied interests, especially in rocks. This interest, combined with his innate ability in mathematics, led him to New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology where he received a bachelor’s degree in geophysics, a “good fusion of mathematics and rocks.”

He stayed at New Mexico Tech to earn a master’s degree in hydrology. From there, he came to Texas and worked nine years at the University of Texas’ Bureau of Economic Geology, earning his doctorate in hydrogeology from the University of Texas during this time.

While working at the bureau, Mace led a project studying the natural attenuation of spills from gasoline stations.

“People started noticing that contaminant plumes would decrease in size with no human interaction,” Mace said. “Naturally occurring bacteria were cleaning up the sites.

“Working on that project was satisfying and a lot of fun. I was bit by the bug,” he said, referring to a project that had policy implications.

Working at the state’s water agency

Throughout his 18 years at TWDB, Mace held several positions, starting out as unit leader for the groundwater availability modeling unit and ending as deputy executive administrator.

As deputy executive administrator, he led the board’s water science and conservation programs, including municipal and agricultural water conservation, environmental flows and groundwater programs. He also oversaw the innovative water technologies program, which included activities related to desalination, aquifer storage and recovery, rainwater harvesting and water use, and flood mitigation planning. He testified frequently at Texas Legislative hearings and spoke to reporters about agency programs.

Mace considers his biggest accomplishment while at TWDB was the task that he joined the water agency to work on: the groundwater availability modeling program.

Inspired by stakeholder involvement in the regional water planning process, the board wanted to have stakeholder input in the development of the state’s first groundwater availability model, a model of the Trinity Aquifer in the Hill Country. Mace directed the team that developed the groundwater model and became the main communicator of the project’s science.

From there, he went on to lead the statewide program for developing groundwater availability models for major aquifers in the state.

Often scientists have their hearts in the right place to bring science to the real world and to the policymakers and decision-makers, but they are talking way over the heads of the people they are trying to communicate to, which means they are not communicating.

Mace said developing the models was important in the groundwater management process for the state, describing the models as “aquifers in a computer.”

With the models, planners can establish desired future conditions by simulating how the aquifer responds to pumping and changes in recharge, and access how much groundwater is available for use.

“We wouldn’t have desired future conditions if we didn’t have those models,” he said.

While his first task at the agency was his biggest accomplishment, his last one presented his biggest challenge. Mace said after the 2015 Wimberley floods and Halloween floods in Austin and elsewhere in the state, the Governor’s office gave the water agency about $6.8 million to advance early warning detection systems to arm Texans with the ability to make informed decisions during floods. The board also moved the state coordinator’s office for the National Flood Insurance Program under Mace.

“So the challenge was suddenly getting this new program, this new issue, with a great deal of attention by the Governor’s Office and legislative leadership of the Texas Capitol as well as a lot of attention by the press,” he said. “We had very ambitious deadlines with a lot of moving parts and lots of things to learn. That was a big challenge but very rewarding because the agency’s staff rose to the occasion, met expectations and made the state safer.”

Entire new programs, such as the TexMesonet, a statewide network of weather stations to support flood monitoring and flood forecasting efforts, were developed, and new streamflow gages were installed.

Mace and his team also began working on the first state flood plan, although it is still in development.

Communicating science and policy

It’s from his early work at the bureau and then at TWDB on the groundwater availability modeling program that his understanding of the power of communications and working with stakeholders began and was carried through his various positions at TWDB and is now an integral part of his Meadows Center position.

From his initial TWDB job, Mace said he learned to work well with stakeholders and to communicate science to nonscientists so that they not only understood the science but also became advocates of the science and the tools that science produces.

"Scientists can feel like they have all the answers and know exactly what needs to be done,” he said. “When working with stakeholders, you learn that maybe you don’t have all the answers or maybe you are focusing on the wrong problem.”

Recognized as an excellent communicator, Mace travels throughout the state and the United States, presenting on topics ranging from groundwater management to drought to the history of windmills. He has authored or coauthored more than 200 reports, papers and abstracts, and given more than 200 speeches on water.

He has received numerous awards, including being inducted into the Texas Water Innovation Hall of Fame by AccelerateH2O in Austin. He is a founding member of the Texas Water Journal, an online, peer-reviewed journal about water in Texas. Recently, Mace was instrumental in launching a new newsletter, Texas+Water, published jointly by the Texas Water Journal, The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment and the Texas Water Resources Institute.

“The Texas Water Journal has been great in providing a peer-reviewed outlet for policy and science papers specific to Texas,” Mace said, “And Texas+Water is going to help us to communicate science and policy to

the public. The Texas Water Resources Institute has been a critical partner in both of those efforts.”

Texas at the forefront of water research

In his long career in Texas water, Mace has observed not only some overwhelming challenges to meeting Texas’ future water needs, but he also has seen how the state has met some of the challenges with groundbreaking innovations.

The chief challenge for Texas water, Mace said, is implementing the state water plan, a plan that is developed every five years, based on 16 regional water plans, and addresses the needs of all water user groups in the state during a repeat of the drought of record that the state suffered in the 1950s.

When working with stakeholders, you learn that maybe you don’t have all the answers or maybe you are focusing on the wrong problem.

“With every plan that comes out, we are falling further behind in being able to meet those needs during a repeat of the drought of record,” he said. “And the state water plan doesn’t solve all the problems because we could have worse droughts than the drought of record. But if communities plan for drought, we are sitting in better place than if we don’t have those plans.”

Mace said the communities that struggle the most with developing drought plans are the rural communities. Rural Texas needs financial help in the form of grants so they can do what they need to do to get ready for these droughts of record.

To help urban communities, Mace suggested that tools need to be developed to help local policymakers better communicate the value of being ready for these droughts.

But, it is also because of these issues Texas has faced that the state has led the world in solutions, Mace said.

For example, he said, the engineered wetlands around Dallas, such as the North Texas Municipal Water District’s East Fork Wetland Project, are the first of their kind in the United States, and Texas has the second and third direct potable reuse water treatment plants — Colorado River Municipal Water District’s Big Spring plant and the city of Wichita Falls temporary plant — in the world.

El Paso Water Utility is collaborating with a private company, Enviro Water Minerals, to harvest minerals out of desalination brine, which, Mace said, puts more freshwater into El Paso‘s water distribution system and decreases — if not eliminates — the amount of water the utility has to inject into its disposal wells.

“Texas has gotten a lot of worldwide attention because of those efforts,” Mace said.

Mixing things up

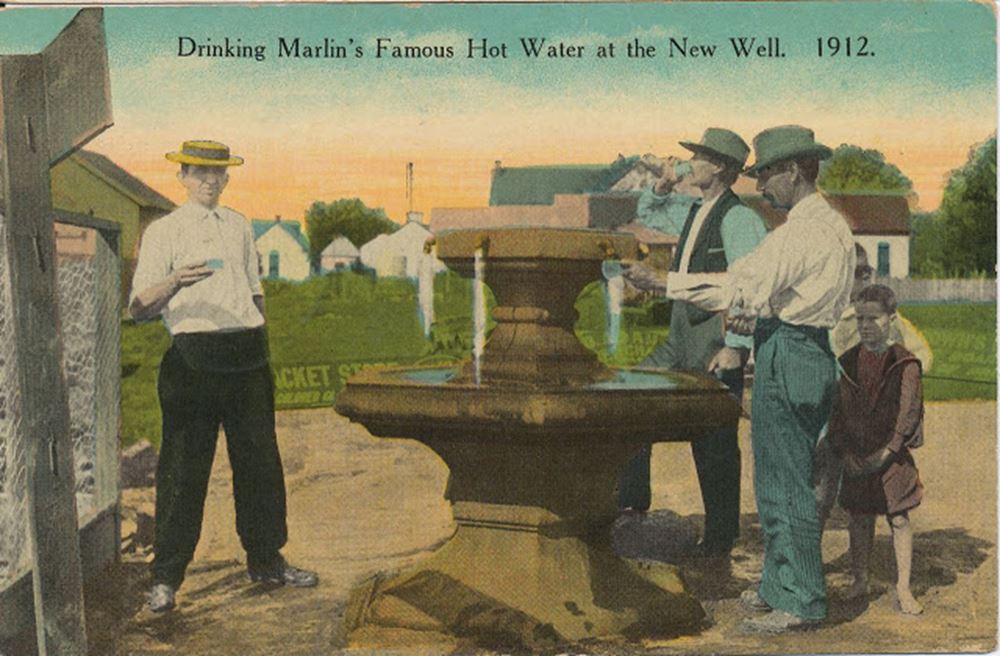

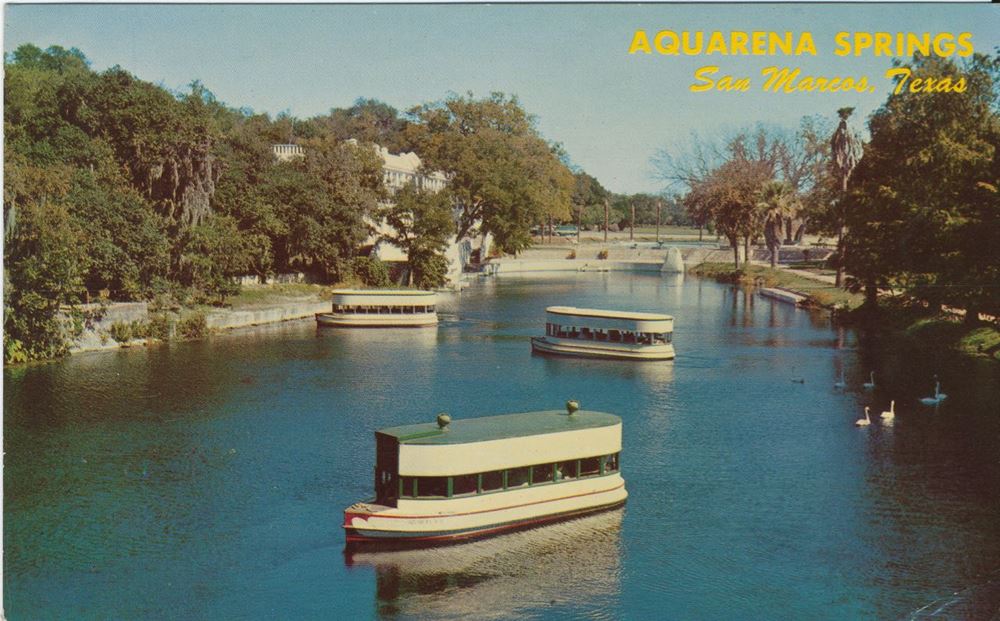

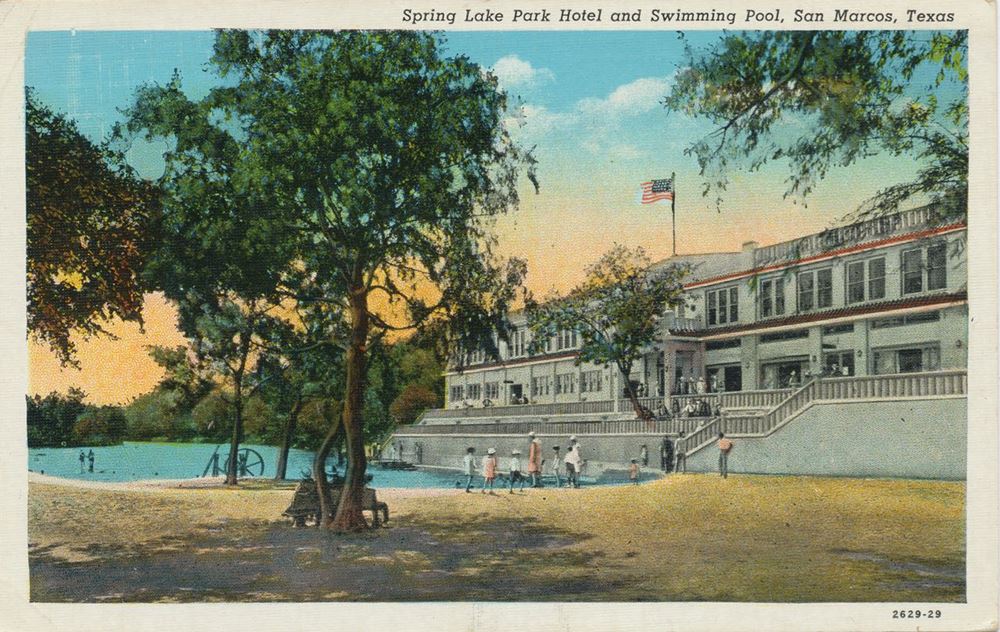

As he did growing up, Mace still has many interests, ranging from collecting artesian wells postcards to researching the history of windmills and the history of modern architecture. He is particularly interested in R. M. Schindler, an Austrian-American architect who sparked Modernism in the United States, according to Mace.

He has combined his ability to communicate and his wide-ranging interests to develop blogs about Schindler (thermschindlerlist.blogspot.com), Austin architecture (austincubed.blogspot.com) and artesian wells (youhavewatermail.blogspot.com). Since leaving the board, he’s also started a blog on Texas groundwater (sosecretoccultandconcealed.com).

If he hadn’t become a hydrologist, Mace said he probably would have been an architect because he loves to build things and has what he calls “a deep love of architecture.”

“I’d like to think I would be a green architect, worried about water conservation and energy conservation,” he added.“At one point in high school, I was going to be a design engineer because I loved to draw,” he said. “I liked to draw schematics. I liked science fiction, and I would design my own spaceships on paper and have cross sections.

“I’d like to think I would be a green architect, worried about water conservation and energy conservation,” he added.

When asked why he decided to leave TWDB, Mace answers with his characteristic humor.

“Three things happened early last year. One, I turned 50; two, I became eligible to retire from the state; and three, David Bowie died.

“I asked myself ‘what do I want to do with the rest of my working career,’” he said. “I loved the people I worked with, loved the mission, loved the board members, but I decided I wanted to mix things up a bit.”

In his position at the Meadows Center, Mace will draw on his experience, knowledge and even his witty personality to continue to make an impact on Texas water.

Three things happened early last year. One, I turned 50; two, I became eligible to retire from the state; and three, David Bowie died.

“I’m an occasional DJ with varied music interests, so I like to fuse different genres, something the kids call ‘mash-ups,’” Mace said, who, as DJ Spaghetti, performed at a SXSW showcase back in the 1990s and wrote a dance-floor track titled “GIS is More Fun Than Beer.”

“The water world is no different in that it’s multidisciplinary. We need to mash-up the disciplines to create science and policy relevant to today’s world. I want to be at the decks and help with the mixing.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As the former communications manager for TWRI, Kathy Wythe provided leadership for the institute's communications, including a magazine, newsletters, brochures, social media, media relations and special projects.