The Rio Grande is a convergence point. Established as the U.S.–Mexico border in 1848, the river travels through two countries, three U.S. states, four Mexican states and numerous cities, irrigation districts and farms.

It’s therefore fitting that the slogan of Brownsville, Texas’ easternmost city on the Rio Grande, used to be “Crossroads of the Hemisphere,” said Jude Benavides, Ph.D. Benavides is an associate professor in the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley’s School of Earth, Environmental and Marine Sciences.

“I think the slogan was initially intended to be crossroads as far as economics, the coastline and the land and the border between the United States and Mexico,” Benavides said. “But I think it also sufficiently describes our situation as far as our ecosystems, modified or not by humans.”

As the region’s population grows and the climate warms, working together to share the river’s water is more important — and harder — than ever, said Bill Hargrove, Ph.D., former director of the University of Texas at El Paso’s Center for Environmental Resource Management.

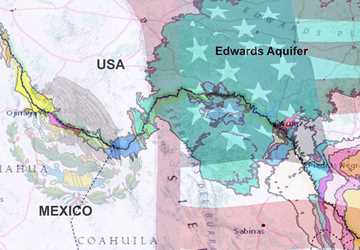

“We draw out of the same river, and we draw out of the same aquifers. So it really behooves us to try to cooperate and manage the water to the best of our ability, instead of just using it as fast as we can,” Hargrove said.

With less water available and more water being used, competition on the Rio Grande is getting trickier. Experts are thinking about cooperative solutions.

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

More Information

Want to get txH20 delivered right to your inbox? Click to subscribe.

Shrinking supply and growing demand

Working together along the Rio Grande wasn’t always as necessary as it is now, Hargrove said.

“There was less need for cooperation in the past because there was more water and people were kind of content with what they had. It was a little less contentious, a little less competitive,” Hargrove said.

The reason competition for water has increased comes down to a simple economics principle.

“The supply is going down and the demands are going up. That’s it,” Hargrove said.

The Rio Grande region already tends toward heat and dryness, and it’s getting more extreme as the climate changes. In El Paso, where Hargrove works, the long-term average number of days with temperatures over 100 degrees is 15. In the summer of 2020, there were 57.

“The supply of water is going down mainly because of warmer temperatures, which are producing less snowpack in the headwaters, so there’s less flow in the river for the most part, and the quality of the water is lower,” Hargrove said.

Meanwhile, the demand for water is increasing: In Texas alone, the population along the Rio Grande has more than quadrupled since 1950. Benavides said that all those people mean that far more water is being used than was ever planned for.

“Our entire water distribution and drainage system in the Rio Grande Valley is built off the backs of an irrigation system for agriculture built 75 to 125 years ago,” Benavides said. “I don’t think any of those folks in the 1920s envisioned that on both sides of the border we would have over a million people.”

We draw out of the same river, and we draw out of the same aquifers. So it really behooves us to try to cooperate and manage the water to the best of our ability, instead of just using it as fast as we can.

Bill Hargrove, Ph.D.The faces behind the numbers

Working together starts with having enough data to base your work on, said Alfredo Granados Olivas, Ph.D., professor at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez’s Institute of Engineering and Technology.

“Hydrology is a monster that changes every day, so it’s not something that’s really easy to manage. If you don’t have a way to monitor, you’re lost,” Granados Olivas said.

Benavides agreed that the Rio Grande region is still somewhat data-poor. “If you were to wipe all the other shared resource problems off the table, you would still have issues because you’re data-limited,” Benavides said.

But just expanding research and data gathering in the region isn’t enough to foster collaboration, Granados Olivas said.

“It’s not just about the numbers. There is a face behind the number, and there is an economic issue behind the face,” Granados Olivas said.

The people behind those numbers often don’t feel heard by each other, Hargrove said.

“It’s really complicated. People in agriculture say, ‘People in the cities don’t appreciate that we produce food for people,’ and the cities say, ‘People don’t appreciate that we try to provide cheap water or how difficult it is.’ And then the people from the environmental groups say, ‘People don’t understand the benefits of different water management schemes for the environment.’”

Hargrove said all that competition — especially for a resource as vital as water — creates a lot of stress and fear, especially if people are already pressed for money and resources.

“People feel very threatened. They feel like ‘blank’ is trying to take our water. And ‘blank’ can be filled in with the federal government, the state government, the cities, the public, environmental groups or irrigators,” Hargrove said.

It’s not just about the numbers. There is a face behind the number, and there is an economic issue behind the face.

When Hargrove was at a meeting in Chihuahua in 2019, a fellow participant summed up people’s fears. “He said the problem is that all the cheap water is gone. And that’s a problem for us. Because the easy solutions, the cheap water — there isn’t any,” Hargrove said. “All of our alternatives that are left are hard and expensive.”

Steps in the right direction

Solving the Rio Grande region’s water struggles starts at home with more involvement from those who rely on the basin, said Rosario Sanchez, Ph.D.

“That’s the only way that they would have a voice or a little bit of knowledge on the current conditions of water in the basin,” said Sanchez, Texas A&M AgriLife Research senior scientist at the Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI) and director of the Permanent Forum of Binational Waters.

Collaborative efforts have seen success in the region. For example, El Paso Water, the local utilities provider, is working with the local irrigation district to capture stormwater runoff that would otherwise be lost downstream because of the area’s slope towards the river. Additionally, the partnership is reforming old wastewater holding ponds to store runoff for both agricultural and municipal use.

Our entire water distribution and drainage system in the Rio Grande Valley is built off the backs of an irrigation system for agriculture built 75 to 125 years ago. I don’t think any of those folks in the 1920s envisioned that on both sides of the border we would have over a million people.

Far to the southeast, the Brownsville Public Utilities Board is collaborating with the city of Brownsville and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to restore resacas, former channels of the Rio Grande that are naturally cut off from the river. Many resacas have been filled in over the years, removing valuable habitat and natural floodwater storage.

“Fresh surface water of any kind here, even if it’s mildly brackish, is precious to the environment, to the ecosystem,” Benavides said.

Not far from Brownsville, the Arroyo Colorado Watershed Partnership has brought together TWRI, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board and other organizations to improve issues such as flooding, drainage, habitat and water quality.

Thanks to the partnership’s work, 10 wastewater treatment facilities have been created or upgraded, centralized wastewater service has been provided to over 17,000 residents in 42 colonias, and best management practices have been adopted on 130,000 acres of irrigated croplands.

“We had the right mix of experts — people who were from here or had a passion about this region. All of that coming together enabled the Arroyo Colorado Watershed Partnership to get started on a very strong footing,” said Benavides, who chairs the Arroyo Colorado Watershed Partnership’s steering committee.

Along the entire Rio Grande, the newly created Permanent Forum of Binational Waters is fostering conversation and collaboration across state and international borders through a network of specialists, academics, citizens and scientists. Sanchez wants the forum to help pave the way for bigger changes.

“We definitely need someone or a couple of someones to actually take the lead on this. That’s what we’re trying to do in the forum,” Sanchez said. “But we need much more than that — bigger, stronger definitely, and willing to actually do something.”

Holistic, long-term solutions

Existing collaborations are steps in the right direction. But to face the increasing population, temperature and drought, Benavides said more cooperation efforts are going to have to get a whole lot bigger.

“This region is fragmented by design, politically. In the Rio Grande Valley, our legislature and congressional districts split the valley. The same is true with counties in this region, states, upstream, downstream, left bank, right bank, north bank, south bank,” Benavides said. “And with all of those competing interests, not enough people are looking at this problem from a holistic standpoint.”

If people don’t look at the whole problem, they won’t be able to hear each other, feel heard or create whole solutions, Benavides said.

“We have to be honest about what we as a region are, where we were, in order to know where we want to be,” Benavides said. “The better we understand the way this area functions naturally, the better we’re going to be able to make the most out of how the future changes climatologically and anthropogenically. To look at the situation in a vacuum without that I think is folly anywhere, but particularly here.”

Especially as drought becomes more frequent, solutions must also focus on the long term, Granados Olivas said. He added that creating holistic, long-term cooperative solutions will require teaching society about the scientific nuances of the Rio Grande region’s water woes — and teaching scientists and decision makers more about society.

“If we don’t frame society in teaching what the issue is, then we are going to have a big loophole in there in reaching decisions. You have to connect to what’s really happening out there, bring it into real life,” Granados Olivas said. “People who want to solve these problems have to understand economy; they have to understand technology; they have to understand society.”

The better we understand the way this area functions naturally, the better we’re going to be able to make the most out of how the future changes climatologically and anthropogenically.

Jude Benavides, Ph.D.One size won’t fit all

Even if future solutions are holistic and long-term, no one solution will solve all of the Rio Grande region’s water supply and demand troubles, Hargrove said.

“The real solution for the future is some kind of combination of all these things. You have to have some kind of integrated strategy moving forward that includes both developing new supplies and reducing demand,” Hargrove said.

Technological solutions such as desalination can help fortify existing water supplies and develop new supplies, while conservation measures such as shifting to drip irrigation over flood irrigation can help decrease water demand. Improved water allocation measures can help on both the supply and demand sides.

Benavides emphasized that everyone working on those different solutions will need to work in tandem. “None of us are going to be able to solve the problem alone. It’s not going to be the academic sector alone or the private sector alone. It’s going to take all of us,” Benavides said. “Unless we get to work fast, this is going to become a very, very big problem very soon.”

At the crossroads

For Benavides, looking for water solutions comes back to Brownsville’s old slogan, “Crossroads of the Hemisphere.”

“I think this region needs to be a focus point, a meeting point for bringing folks from upstream, downstream, north of the border and south of the border truly together,” Benavides said. “I think that’s going to be our golden ticket really: to find out where we can overlap, where we can make a synergistic use and development of water and water resources in this area.”

Meanwhile, Granados Olivas will soon be putting his ideas about collaborative solutions into action in his own backyard. His ranch will serve as a training center for producers, where they can learn about new technology, water conservation and other ways to reduce their costs and increase their yields.

“My philosophy here is really simple. My plot has 50 hectares. My biggest concern is that my neighbors are as successful as they can be in water conservation, and then they have to do that with their own neighbors, and so on and so forth. You have to take care of your neighbors,” Granados Olivas said.

Strong communities are the ones that are working on the base, on the people. If you solve the issues of food, water, energy and health, you have the potential for growth, art, music and literature, and that’s a different society.

“Strong communities are the ones that are working on the base, on the people. If you solve the issues of food, water, energy and health, you have the potential for growth, art, music and literature, and that’s a different society,” he said.

Benavides hopes that finding cooperative solutions to the Rio Grande’s water supply and demand issues can keep the region flourishing for years to come.

“Water has been here, remains here and makes it all possible. I’m a fifth generation northeastern Mexican, and now I’m a second generation American. I hope that one or both of my two kids decides to remain here. I’m intensely proud of this region having done what it’s done well,” Benavides said. “I hope to continue to make sure that we have enough water and the right quantity and quality to keep this place as beautiful as it is to us.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As a communications specialist for Texas Water Resources Institute, Chantal Cough-Schulze worked with the institute’s communications team writing articles for and editing txH2O magazine and TWRI's news section, developing TWRI multimedia materials and editing reports and education and outreach materials. She also served as the managing editor for the Texas Water Journal.