The water of the Rio Grande drew people to the area and it — via irrigation — made the desert bloom into a garden of agricultural abundance.

Without irrigation, agriculture along the Rio Grande would not look the same. According to the 2018 Census of Agriculture’s Irrigation and Water Management Survey, the incomes of over half (52.6%) of U.S. farms in the Rio Grande water resource region are completely dependent on irrigation.

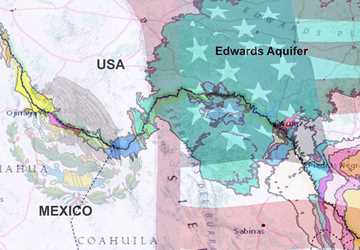

However, Rio Grande irrigators know the availability of the river’s water is increasingly uncertain as urban populations in the region grow. Over the past decade, the major paired U.S. and Mexican cities along the border — El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, Del Rio and Ciudad Acuña, Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras, Laredo and Nuevo Laredo, McAllen and Reynosa, and Brownsville and Matamoros — have added over a half million more people to the banks of the Rio Bravo, as it is called in Mexico.

With urban growth expected to continue, agriculture dependent on the Rio Grande must be ever more water efficient. Producers in the area know this; the Irrigation and Water Management Surveys show that three out of every four area farmers and ranchers listed water conservation as a priority in 2018. That number was only two out of three in 2008.

Luckily, numerous water efficiency strategies are already available, and research is ongoing to improve it even more. Examples include the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative-funded projects looking at salt-tolerant pecan rootstocks, the viability of switching usual Texas cash crops to quinoa or pomegranates and indoor vertical farming discussed elsewhere in this issue.

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

There are numerous barriers to Rio Grande irrigators adopting more and better water saving measures, but better understanding and a shift in perspectives and incentives could help bridge the gap.

More Information

Want to get txH20 delivered right to your inbox? Click to subscribe.

However, continued improvement of water efficiency in Rio Grande-area agriculture means the need for change, and change is always a challenge.

The high cost of change

Change means costs. That can be a problem in agriculture where margins are often razor thin even in a good year.

“I can tell you that for a producer to adopt a practice, it’s got to be cost-effective first,” said Allen Berthold, Ph.D., Texas A&M AgriLife Research assistant director of the Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI). In addition to his role with TWRI, Berthold comes from a farming and ranching family and ranches himself. He has a strong connection to the concerns of Texas farmers and ranchers because he is one and shares their concerns.

“You can bet I’m not going to do something that’s going to cost me a bunch of money,” he said, speaking as a producer. “If it’s going to cost me a lot of money to invest in something that I don’t get a whole lot of return on, why would I do it?”

“Cost” usually refers to money, but it can also mean things like the time and frustration involved with learning new, unfamiliar technologies or practices. It can also mean the opportunity cost of doing something different; if the “old way” of irrigating a crop was producing a good yield, the potential for reduced yields if something is changed is a steep cost.

All of these costs were highlighted in a past effort by the Texas Project for Ag Water Efficiency (AWE) to encourage the adoption of automatic surge flow valves for furrow irrigation. AWE was a program of the Harlingen Irrigation District funded by a grant from the Texas Water Development Board from 2005 to 2015. Even though the group estimated the water savings associated with the technology at anywhere from 22 to 52% in the Lower Rio Grande Valley depending upon crop, adoption was low.

The monetary expense of the technology was high. One automatic surge flow valve can cost a couple thousand dollars in addition to the cost of the necessary piping. But the “costs” associated with the technology didn’t stop there; the new and increased operation and management was a concern too.

“They were very hard to work with,” said Victor Gutierrez, AgriLife Extension associate with TWRI. In addition to his role at TWRI, Gutierrez comes from a farming family in the Lower Rio Grande Valley and regularly helps them with on-farm needs.

“A lot of these ranch hands or farm hands don’t know how to work with that technology,” he said. “It wasn’t very easy or friendly to operate.”

Gutierrez added that some of the producers he worked with said the cost, time and effort related to the technology wasn’t worth it for them and their operations; it just didn’t pencil out.

“There are a lot of technologies out there, but the fact is they are expensive and I don’t know if people would see the profits back if they invested in something like that,” Gutierrez said.

If it’s going to cost me a lot of money to invest in something that I don’t get a whole lot of return on, why would I do it?

Many share his skepticism. In the most recent Irrigation and Water Management Survey, a third of respondents from the Rio Grande water resources region said they could not finance water-saving improvements to their operations. Another 15.6% said they didn’t think the cost of improvements would be covered by the savings those improvements might create. Opportunity costs were also of strong concern; almost a fifth of respondents were worried that water conserving measures would reduce yields and another 7.4% feared improvements would increase their management costs.

In addition to direct costs, structural barriers stand in the way of irrigators’ adoption of water-saving technologies and methods. While most acknowledge that freshwater availability is uncertain and more people see water conservation as a priority, the structural incentive to save water just isn’t there.

“Overall, the cost of water is so cheap that it’s hard to encourage people to use less,” Berthold said. “Plus, why would a producer risk a much lower yield and less income when putting a little more of something so inexpensive guarantees maximum yields?”

Though exact pricing for irrigation water varies by irrigation district, a common price is $20 per acre foot. With an acre foot of water being 325,851 gallons, this cost of irrigation water isn’t even measured in pennies per gallons, but rather gallons — almost 163 of them to be exact — per penny.

There are other charges involved with irrigation costs — general tax, wasted water fees, delivery costs depending on location, maintenance fees and more — that can more than double the functional per-acre foot of water charge. However, even in that situation, irrigation water is still valued in gallons per penny.

When it comes to the effort to improve water efficiency, particularly in the face of the steep cost of change, the relatively low cost of water sends a mixed message.

“That’s always been the struggle with water conservation down there,” said Lucas Gregory, Ph.D., Texas A&M AgriLife Research assistant director of TWRI. In addition to his role at TWRI, Gregory grew up in a grass-farming family that raised forage for cattle.

“It just doesn’t pay because water is a literal drop in the cost bucket in the Valley, so there is no economic incentive for irrigators to conserve water in many cases,” he said.

It gets back to the economics; producers won’t be willing to invest in those unknowns.

Looking to the future of the Rio Grande and irrigation

Overcoming the costs associated with increased adoption of water-saving technologies and practices in agriculture along the Rio Grande is an ongoing effort and one that will require a multi-pronged approach. However, a producer- and economics-focused perspective must be part of any effort.

“I’ve had some discussions with growers down there about what they would be willing to do if money was not an option and many of them are interested and eager to try things, but it all ties back to economics,” Gregory said.

He, Berthold and Gutierrez — being researchers as well as coming from agricultural backgrounds — all stressed the importance of pragmatic, real-world approaches to addressing the costs associated with pursuing solutions to water issues in agriculture along the Rio Grande.

“If we can show them something saves money, whether it be a labor savings or something else, then they’re in, but until you can do that, they’re going to be hesitant,” Gregory said.

A potential way to lower the costs of water efficiency improvements could come from the irrigation districts, Gregory said. He explained that most Rio Grande-area water districts charge by the irrigation, using rule-of-thumb estimates of water use per irrigation, rather than by the actual volume of water used. If producers who use less than the assumed volume could save money, “then I think you would have a lot more people buy into it,” he said.

Unfortunately, such a possibility would require volumetric pricing, which comes with its own set of adoption challenges with the meters necessary to make it work. Water meters for agricultural use are expensive, are often stolen and can come with operational difficulties.

“Old-school propeller meters were tried down in the Valley, but they did not work well,” Gregory said. “The main complaint I heard from growers was that they got plugged up with trash and fish, and increased labor needed to keep irrigation going.”

Newer meter technology that uses doppler or ultrasonic technology is available that bypasses the issue of debris in the water, but they are still expensive.

“It gets back to the economics; producers won’t be willing to invest in those unknowns,” Gregory said. “That’s really where AgriLife comes into play. If we can get the funding to do these demonstrations and really prove some of these things as practical, I think you’re going to see a lot more buy in.”

The need for change doesn’t rest only on producers. Everyone along the Rio Grande, including the growing urban population, depends on the finite water resources the river offers.

“The fact that urban spaces and urban water demands have grown so quickly has been an unprecedented change to the region and its agriculture. There have always been water shortages during drought times, but the river never had this level of demand on it in the past,” Berthold said.

“Under ideal conditions, urban people would adapt to a desert mindset,” Berthold added. He acknowledged that such a shift would require expensive city infrastructure changes that present their own adoption challenges, but it would be ideal, nonetheless. “If urban water consumption was static instead of rising, that would reduce that competing demand on water for agriculture.”

Similarly, since the Rio Grande is a shared river between the U.S. and Mexico, the need for change does not fall only north of the border. Much of the flow of the Rio Grande in Texas is dependent on what happens upstream in Mexico. According to the 1944 Treaty for the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers, Mexico must deliver a five-year water quota of 1.75 million-acre feet (about 570 billion gallons) from the Rio Grande to the U.S. In recent decades, Mexico has often waited until the fifth year to deliver all the required volume rather than spreading the amount out over the five years. This makes the river’s flow in Texas less than consistent or dependable.

Berthold, Gutierrez and Gregory said that Mexico should release water annually to keep the flow of the Rio Grande in Texas more consistent. Without a dependable, consistent supply of water from the river reduces Texas producers’ abilities to irrigate strategically to the needs of their crops. According to recent Irrigation and Water Management Surveys, the number of Rio Grande producers scheduling their irrigations based on water supply more than doubled from 22.3% in 2008 to 46.4% in 2018.

“Pretty much all of us are dependent on the river, and we’re dependent on that treaty that was signed between the U.S. and Mexico,” Gutierrez said.

Ultimately, overcoming the barriers to increased water efficiency and conservation in irrigation along the Rio Grande will take change on a large scale, and it will take more than just area irrigators to make it happen.

“You have to see the picture in the whole,” Gutierrez said. “You have to get everybody together, and that’s a challenge.”

Irrigators have done good work over the years to become ever more water efficient, but Gregory said the situation cannot stagnate; things must continue improve all along the Rio Grande to preserve water availability for all water users in the area going forward.

“The challenge is going to be getting people to look at things from a different perspective and be willing to change the way they currently operate,” he said. “You are starting to see a change in the mentality, but it all hinges on the economics.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As communications manager for TWRI, Kerry Halladay provided leadership for the institute's communications. As a strategic coordinator, she served as liaison between AgriLife's Marketing and Communications department and the client groups: TWRI, the Natural Resources Institute, the Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture, and the Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases.