Every five years a water clock ticks down to a due date between the U.S. and Mexico. According to a 77-year-old agreement, Mexico must deliver water from the Rio Grande to the U.S. But with ever greater demands on the river and increased uncertainty of its flow due to climate change, those deliveries have faced increasingly tense problems that require ever more collaborative, flexible, human answers to solve.

The year 2020 was one where the water came due and Mexico had to delivery on its five-year water quota from the Rio Grande to the U.S. under the 1944 Treaty for the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers (1944 Treaty). Though this delivery obligation was often called Mexico’s “water debt” in the mainstream news media in the U.S., according to the treaty, actual “debt” does not occur until the deadline passes without full deliveries being made.

Prior to the Oct. 24 delivery deadline, tensions strained to the breaking point in Mexico. Farmers from the Mexican state of Chihuahua protested the government delivering water to the U.S. aggressively throughout the year. They were angry that what they felt was their water — the means to their livelihood — was being given away.

Tensions were exacerbated by demands from north of the border as well where many Texas farmers were angry because they felt their water was being withheld. In a Sept. 15, 2020 letter to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott called the waters of the Rio Grande vital to Texas agriculture as well as municipal and industrial needs.

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

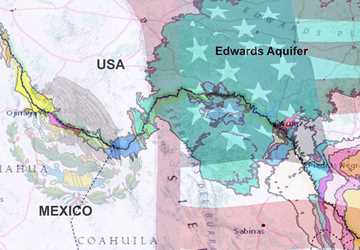

The U.S. and Mexico are divided by the Rio Grande, but the two countries must come together to solve their water delivery problems because it is just one river.

More Information

Want to get txH20 delivered right to your inbox? Click to subscribe.

Carlos Rubinstein — past chairman of the Texas Water Development Board and past commissioner and Rio Grande Watermaster for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality — spoke at the first “Coffee Break” event held by the Permanent Forum for Binational Waters on Aug. 26 to discuss the delivery situation. He told attendees that the situation should not surprise anyone who has paid attention to the history of the Rio Grande.

“We’ve seen it before. It’s not a surprise,” he said.

Samuel Sandoval Solis, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources at the University of California, Davis and Cooperative Extension Specialist in Water Management, had much the same to say at the Coffee Break event. He called the tensions leading up to the deadline “a story repeating.”

The beginning of the troubled water sharing story

Today’s tensions over the water debt are rooted in a long history of disputes that go back to the U.S.-Mexican War and the shaping of the two countries as they exist today. The war ended with the signing of Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848 and with the U.S. annexing over half of what had been Mexico. That ceded territory today represents the U.S. states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, part of Colorado, and Texas west of the Nueces River. This territory included the headwaters of the Rio Grande in the mountains of what is now Colorado.

The adaptability of the 1944 Treaty is pretty unique. You hardly find this in any other water sharing treaty in the world and definitely not between the two countries.

Beyond using the Rio Grande and other rivers including the Colorado and the Gila as boundary markers between the two countries, the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo said nothing about water sharing. That topic was first addressed in the Convention of 1906 for the “Equitable Distribution of the Waters of the Rio Grande.” The agreement stipulated that the U.S. would deliver 60,000 acre feet (about 19.5 billion gallons) of water annually to Mexico from the upper portion of the Rio Grande ending at what is now El Paso/Ciudad Juarez.

The Convention of 1906 laid the groundwork for the 1944 Treaty, which outlines water delivery requirements between the two countries and created the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC, or Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas in Mexico) to implement the treaty.

Under the 1944 Treaty, the U.S. is required to deliver 1.5 million-acre feet (about 489 billion gallons) to Mexico annually from the Colorado River. Meanwhile, according to the treaty’s Article 4, Mexico is required to deliver 1.75 million-acre feet (about 570 billion gallons) of water to the U.S. from the Rio Grande every five-year cycle. If U.S. storage at the Amistad and Falcon reservoirs reach full capacity within the five-year period, however, the cycle ends and a new one begins. The treaty additionally “forgives” all debts if at any time during a cycle the U.S. storage at both reservoirs reach 100% capacity.

The 1944 Treaty also outlines that if Mexico is unable to make this minimum delivery every five years, such as in the case of extraordinary drought, the deficiencies “shall be made up in the following five-year cycle with water” from some Rio Grande tributaries. This allows for what some have begun calling Mexico’s water debt to build over the years.

In the recent past, when Mexico either built up a water debt to the U.S. or otherwise struggled to make deliveries from the Rio Grande, other strategies were used. Specifically, Article 9 of the treaty allows the commission to be flexible in making water deliveries from other tributaries to pay or augment the water deliveries. For example, in 2015, water from the San Juan River was delivered to reduce the amount of shortfall that would exist at the end of that cycle.

Speaking of that agreement, Mario López Pérez said both Mexican and U.S. negotiators had focused on the main goal of getting water to the U.S. in 2014-2015. López was a past coordinator of hydrology at the Mexican Institute of Water Technology (Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua) as well as the former engineering and binational water affairs issues manager at the National Water Commission (Comisión Nacional del Agua) of Mexico.

“Treating the United States as the first obligation in the allocation of the water, that was our main goal. As an example of that kind of agreement to honor our words, we agreed with Texas. We went directly to the stakeholders,” he explained.

“The United States received the San Juan water in order to reduce the deliveries from Falcon dam. The Mexican water came from excess water from excess runoff from severe storms that occurred in the upper San Juan Basin.”

The fate of Mexico is tied to the fate of the United States, and the fate of the United States is tied to the operations in Mexico. It isn’t one side of the border or another.

Change along the Rio Grande

Change is a reoccurring theme in the list of potential problems that led to this point. In some ways, the 1944 Treaty is uniquely set up for change because of its Minute system. A “Minute” is a small implementation agreement to solve an emerging issue not otherwise addressed by the treaty. There are currently 325 Minutes that have been made to the treaty, the most recent having ended the most recent water delivery issue on Oct. 21, 2020.

According to Sally Spener, IBWC U.S. foreign affairs officer, the strength of the Minute system is that it allows IBWC to develop agreements to implement various aspects of the treaty and adapt over time. It additionally does not require going through the congresses of either country, meaning it can more rapidly and nimbly adapt than most international agreements.

“That is pretty unique. You hardly find this in any other water sharing treaty in the world and definitely not between the two countries,” said Rosario Sanchez, Ph.D., Texas A&M AgriLife Research senior research scientist at the Texas Water Resources Institute and director of the Permanent Forum for Binational Waters. “But the drafters of the treaty never expected a couple of things: population growth and climate change.”

“The number of people living in that area has greatly increased from the 1900s to 2020,” said Luzma Fabiola Nava, Ph.D., researcher for Mexico’s National Council for Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología). Indeed, the populations of El Paso and Cameron counties are more than four times larger today than what they were in 1940, for example. According to U.S. Census data compiled by the Texas County Information Program, El Paso County had about 131,000 and Cameron County had about 83,000 residents in 1940 compared to 839,000 and 423,000 today, respectively.

“So, the demands have increased automatically as more people are living in the area,” Nava said.

More people mean more demands on the water, but there is also the impact of climate change, or “increased hydrologic variability” as López called it.

“Some say it is climate change; others say it is not climate change. We don’t care if it is or not. The fact is there is huge variability in the system. That was not the case when the treaty was signed.”

“At the core, the problem is an overallocation,” he added.

Sandoval said much the same, describing the situation as there being more water on paper than is in the river. He said the treaty allocates as much as 50% more water than regularly flows in the river. Nava agreed, adding that the on-paper water is currently “locked” with the treaty as is.

“That means that taking into consideration all these changes is not possible unless something else happens to modify those quantities that have to be shared among the parties,” Nava said.

Not an easy question; not an easy answer

If there is a problem with water allocation from the Rio Grande, and the 1944 Treaty is uniquely changeable through its Minute system, why not change it?

There are many disagreements about what needs be done to prevent issues like the current situation from developing again. Primary among them is whether the 1944 Treaty should be changed, replaced, or if it is part of the problem at all.

On the one hand, those involved with Texas agriculture have noted that the treaty has no teeth as is; there is no enforcement tool for the U.S. if Mexico continues to repeatedly fail to make its water deliveries. Also, the treaty’s drafters focused on agricultural needs and uses only. They did not know that one day cities would rely on agricultural infrastructure to get their water too. Today those oversights are increasingly palpable as urban populations grow along the Rio Grande and the ecological importance of the river and its systems become better known.

The 1944 Treaty is not the problem. There is a real problem that the population and the uses of the water have dramatically increased along the border, but they also have on the Colorado, and there’s cooperation there. So, something is missing here on the Rio Grande.

Both oversights could argue for a substantial change to the treaty, possibly even a new treaty entirely.

On the other hand, some involved with the treaty and the Rio Grande have noted that there are more human problems underlying issues that must be addressed first.

“The treaty is not the problem. If we can’t comply with this one, what makes you think we can comply with a different one?” asked Rubinstein.

“There is a real problem that the population and the uses of the water have dramatically increased along the border, but they also have on the Colorado, and there’s cooperation there. So, something is missing here,” he said.

“On the Mexican side, they are not setting aside water as a priority for delivery first just like the United States does out of the Colorado. On the American side, we think we have a right to dictate to Mexico on the exact steps it needs to comply. We would not accept that from another country, and we need to show the exact same respect for Mexico. Both sides have taken positions that are counter to finding solutions.”

He additionally opined that selectively reading the treaty is a problem on both sides of the border.

Both sides have taken positions that are counter to finding solutions. On the Mexican side, they are not setting aside water as a priority for delivery first just like the United States does out of the Colorado. On the American side, we think we have a right to dictate to Mexico on the exact steps it needs to comply. We would not accept that from another country, and we need to show the exact same respect for Mexico.

“Read the whole darn thing and empower the people who are sitting across the table to apply the entire treaty,” he urged. “The commissioner of IBWC absolutely has the authority to look at the San Juan, and we have used that in the past. But when you only want to read Article 4 and you want to ignore Article 9, it isn’t a problem with the treaty anymore, is it?”

Nava agreed that the treaty is not the problem.

“The 1944 Treaty, from my perspective, is a very good treaty. It could be better, but as of today, it is very good. It has the institutional capacity to solve our current problems through the Minute process,” she said, adding that the current situation is an issue that needs to be addressed by diplomatic means.

“The current situation between Mexico and the United States regarding water deliveries under the 1944 Treaty reflects how these countries have been managing an issue related to complex changes, including climate, hydrology, demographics, agriculture, pollution and politics,” she said.

“An enormous generation of political will is needed as well as sustained dialog on those socioenvironmental issues.”

The path forward on the Rio Grande

While there are many problems facing the Rio Grande, U.S./Mexico relations over its water and working within the 1944 Treaty, there are also areas of agreement; specifically that there are non-water issues that affect the discussion of water. Many participants in the Coffee Break stressed the need to rebuild trust and foster cooperation between stakeholders.

“The non-water issues become important because they are a big part of the discussion process. You want to feel respected, and you want to feel secure. And this goes in both directions,” said Sandoval. “We need to have improved diplomacy. We need to start thinking how to avoid some of these issues, and how they can be prevented.”

Part of the proactive effort at fostering respect is acknowledging the different needs, interests and concerns of water users on both sides of the border according to Rubinstein and López.

“Part of the issue we have to recognize is that the social, economic and political implications state by state in Mexico are different, and that gets in the way of the ability to comply,” said Rubinstein.

López echoed this, noting that sometimes the water basin councils in Mexico don’t take this into account either.

“The people from Chihuahua do not have the same vision as the people from Tamaulipas. They have different visions. They have different interests,” he said. “And the opinions of the representatives of stakeholders at the basin council level, most of the time it is not the opinion of the people they are representing.”

“But let’s not forget that this is a social issue, a human issue, that we are dealing with and it will take time. It is all is about trust,” he added.

“We need to rebuild trust with the Mexican water users because we have disrespected them. We must rebuild trust in the Mexican basin councils. And we must rebuild trust with the United States and the Texas governments regarding the treaty. We need to learn from the Colorado process.”

Both he and Rubinstein spoke at length about their efforts in the late 1990s through the middle of the last decade. According to López, they sat down and hashed out a practical approach that could work for all stakeholders rather than adopting a top-down, demanding position that puts Mexican farmers on the defensive.

“We agreed with the stakeholders. We explained. We gave them reasons and justifications, explanations that this was going to be different for everybody, not only for the Mexican farmers, but also for the U.S. farmers in Texas,” López said.

Rubinstein also warned that excluding stakeholders from either or both sides is “a great recipe for failure.”

“Harsh positions taken by both sides actually get in the way of what should be an amicable resolution,” he added. “What we did to resolve the issue before was find solutions to not only the problem that was facing us, but to proactively prevent it going forward. That’s what we need to get back to.”

Several of the participants in the Coffee Break said that there must be a shift in mindset related to the river itself and those who depend on it.

“I think all stakeholders need to make a distinction between ownership and a sense of community. It’s not the same thing,” Nava said. “If I own the water, I do what I want because it is my water. But if I belong to the basin community, I care what is happening upstream, downstream and within my area.”

Sandoval echoed this, stressing that it is not and cannot be a U.S. versus Mexico situation.

“The fate of Mexico is tied to the fate of the United States, and the fate of the United States is tied to the operations in Mexico,” said Sandoval. “It isn’t one side of the border or another; the reality is the fate of the farmers is tied together. We need to see this as a shared resource. We just need to realize it’s just one river.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As communications manager for TWRI, Kerry Halladay provided leadership for the institute's communications. As a strategic coordinator, she served as liaison between AgriLife's Marketing and Communications department and the client groups: TWRI, the Natural Resources Institute, the Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture, and the Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases.