Even rivers like the Rio Grande need help sometimes. The Arroyo Colorado is often called “the little river with a big job,” and that job is as a drainage to the Rio Grande and the people and ecosystems that depend on it.

But the Arroyo Colorado also needs some help too, and a partnership of dedicated local, state and federal stakeholders have worked together since 2002 to develop and implement a community-based watershed plan to improve the health and function of this small, but important, tributary of the Rio Grande.

Originally a stream channel of the Rio Grande that provided quality habitat for fish and wildlife, the modern Arroyo Colorado has been modified to carry both commercial barges and, when necessary, flood waters to the sea. It additionally serves as the main drainage stream for the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV) with its flow sustained by wastewater discharges, agricultural irrigation return flows, urban runoff and base flows from shallow groundwater.

The Arroyo Colorado empties into the Lower Laguna Madre, one of only six hyper-saline lagoons in the world. The river is still a productive nursery for fish and other aquatic species and provides bird habitat, as well as premier recreational spaces for fishing, hiking and bird-watching. However, for decades, water quality data in the Arroyo have shown high levels of bacteria that exceed the state’s standards for recreational contact. This is where the Arroyo Colorado Watershed Partnership (ACWP) came in.

Initially organized by two smaller groups of local stakeholders formed in 1998 as part of the State of Texas total maximum daily load (TMDL) process, the ACWP has since grown into an innovative group of local stakeholders and leaders. It collaboratively works with federal, state and private organizations to improve the health and function of the Arroyo Colorado watershed through various projects including working with cities to build coastal wetland habitats, educating farmers on agricultural best management practices and producing public service announcements on urban stormwater.

From beginning to drain

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

The Arroyo Colorado is often called “the little river with a big job.” That job is to be a major drainage and flood control system to the Rio Grande, as well as feeding one of the most unique ecosystems in the world. A dedicated community group, the Arroyo Colorado Watershed Partnership, has been helping this little river do its work.

More Information

- Arroyo Colorado Watershed Partnership

- Update for the Arroyo Colorado Watershed Protection Plan

- When hometown waters draw you back again

Want to get txH20 delivered right to your inbox? Click to subscribe.

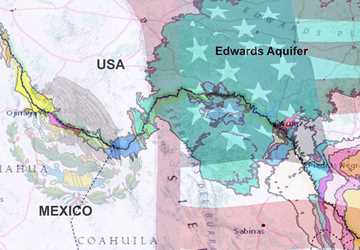

The Arroyo Colorado watershed, part of the Nueces Rio Grande Coastal Basin, covers 420,000 acres of land in the LRGV, located in the southern tip of Texas.

According to Jaime Flores, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension program coordinator at the Texas Water Resources Institute (TWRI) and ACWP watershed coordinator, the Arroyo Colorado is a yazoo river to the Rio Grande. “Yazoo” rivers or streams form over extended periods of time alongside rivers that regularly flood. Strong seasonal flows coupled with flooding events can cause natural levees to form along the banks of a river. When a river with these natural levees flood, they effectively trap water alongside the river once it recedes. This results in parallel tributaries that are only refreshed with flow when the main river floods.

What natural forces first created, human activity expanded, Flores said.

“Because settlers to the area in the early 1900s had the Rio Grande, they were able to access water,” said Flores. “After clearing the native thornscrub and brush to access the rich soil of the Rio Grande Delta, they started creating a huge irrigation system. They started building the canal systems and drainage systems, directing water from the Rio Grande to the irrigation districts where they could easily use it.”

Flores explained that the Rio Grande and the Arroyo played a big role in the development of farms that became the towns and cities that now make up the LRGV as the agricultural hub it is today.

“Each town developed from one farm, or several farms in that one area,” Flores said. “If you look at the Valley, it’s really unique in the sense that it’s got all these little towns and cities that once were farms. Over time, these small towns and cities have grown so much and so rapidly that they have expanded into each other and are now one of the fastest growing metroplexes in the state.”

As the farms grew, so did the discharge demands on the Arroyo Colorado.

“It became a way to get rid of all the excesses used for everyday life. It became a way to drain everything,” he said. “That became the norm. And as we got more wastewater treatment facilities, their discharge went into the Arroyo Colorado.”

While the area started off as a series of farming communities, urbanization of the LRGV began to pick up in the 1980s according to Flores. This has been especially noticeable in recent years.

“Now we’re about 50-50 farm-to-urbanization, whereas 10-15 years ago, it was like 75-80% was still ag use compared to urbanization,” he said.

Even as the LRGV has shifted away from being a predominantly agricultural area, the demands on the Arroyo Colorado for drainage have continued. The impact has been water quality problems in the Arroyo Colorado.

Coming together to solve the problem

“It’s not that water users in the area were deliberately trying to pollute the river, but after 100 years of it, it starts to accumulate,” Flores said of the problem.

He explained that excessive nitrites, nitrates and phosphates from both agricultural and urban land, as well as 24 permitted wastewater treatment facilities that discharge approximately 60 million gallons a day in the Arroyo Colorado Watershed, can cause algae blooms and other water problems. The polluted condition of the river additionally endangers the fragile ecosystem of the Lower Laguna Madre estuary and lagoon.

“The estuary is a nursery for all the shrimp and the crab and fish and the birds,” Flores said.

Because of the invaluable nature of recreation in the Arroyo Colorado, as well as the economic and ecological benefits that come from those species, business leaders, farmers and cities were motivated to form and join the ACWP.

It’s not that water users in the area were deliberately trying to pollute the river, but after 100 years of it, it starts to accumulate.

Flores said the original partnership developed in 2002 from several groups working to reduce pollutants to the Arroyo Colorado. This started out as a TMDL study by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ ) before watershed protection plans (WPPs) existed in Texas.

“The TMDL work group, the monitoring work group, the outreach and education work group all merged to form the partnership,” Flores said.

With support from Texas Sea Grant, TCEQ, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and TWRI, the group published the “Arroyo Colorado Watershed Protection Plan” in 2007.

“It was the first WPP written in Texas. It was a template,” Flores said. “Because it was the first WPP, it was very important for the state.”

Since then, the ACWP published the “Update for the Arroyo Colorado WPP” in 2017, which outlined accomplishments to date, including significant technical and regulatory upgrades to eight wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs), significant decreases in nutrient loading from those facilities and facilitating the increased and/or improved wastewater services to thousands of residents across 42 colonias along the border.

Today there are four different work groups related to the river and each one focuses on a different area of need. The Arroyo Colorado Agricultural Issues Work Group identifies and addresses agricultural nonpoint source pollution in the watershed. The Habitat Restoration Work Group was established to protect the remaining natural habitats in the watershed. The Education and Outreach Work Group was formed to address the low dissolved oxygen and high fecal bacteria in the Arroyo Colorado by increasing public awareness and fostering local stewardship in the watershed. The Wastewater Infrastructure Work Group was established to document the permitted point source WWTFs being discharged into the Arroyo Colorado and work to establish more stringent discharge permits for existing WWTFs.

Everybody comes together. Everybody has their specific job duties within a group, and we just try to do the best we can with stakeholders. It is a big job.

“Everybody depends on the Arroyo Colorado for discharge,” said Victor Gutierrez, AgriLife Extension associate with TWRI who works on the Arroyo Colorado WPP implementation. He says the ACWP is a huge undertaking, but people are getting the job done.

“Everybody comes together. There are a lot of people on these groups. We all get together and when a project comes up, we are all in agreement,” Gutierrez said. “Everybody has their specific job duties within a group, and we just try to do the best we can with stakeholders. It is a big job.”

There are over 700 collaborators involved with ACWP projects. Flores said there has been a lot more cooperation over the years. “It’s very different now compared to how it started. It has kept evolving and growing.”

To date, the ACWP has completed 19 projects made possible with funding from the EPA TCEQ, the General Land Office and the Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board.

The ACWP currently has four community projects: Implementing Agriculture and Rural Management Measures, Tracking and Inventory of On-Site Sewage Facilities, Llano Grande Lake Restoration Project and San Benito Wetlands Phase IV. These projects have all helped to implement the WPP and restore the Arroyo Colorado in some way.

Flores said it is a lot of work meeting with everyone and tackling the complex issues facing the river, but the protection of the Arroyo Colorado relies on everyone doing their part.

“Through these projects, our goal is to protect the Arroyo Colorado, the Lower Laguna Madre and the remaining natural habitat.”

Explore this Issue

Authors

As a communications specialist for TWRI, Sarah Dormire works with the institute's communications team leading graphic design projects including TWRI News, flyers, brochures, reports, documents and other educational materials.